Finding a way to safely incorporate drones into the airspace is one of the biggest challenges facing the industry today, and some think Automatic Dependent Surveillance – Broadcast (ADS-B) might be the answer.

Christian Ramsey, VP Business Development at uAvionix, recently wrote a blog about the challenges and benefits this technology brings, and the importance of regulators identifying ADS-B as a quick standard that can be developed, released and required for risky UAS operations.

So what exactly is ADS-B and how can it help UAS? It’s an internationally standardized aviation technology that is mandatorily being installed in airplanes and helicopters all over the world, according to Ramsey’s blog.

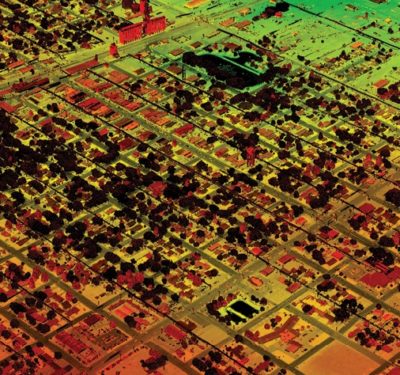

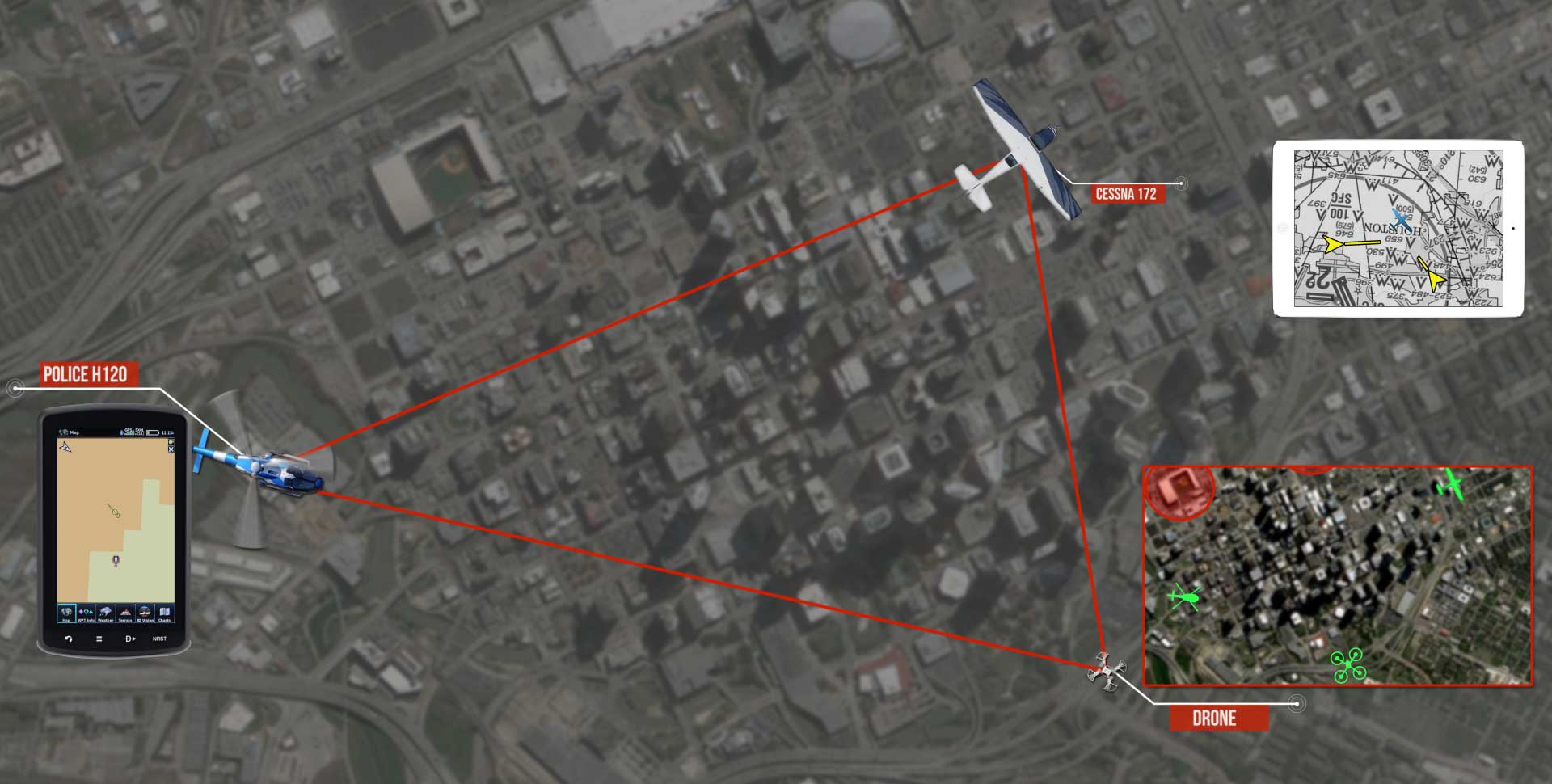

The ADS-B avionics announce an aircraft’s identification, position, altitude and direction to Air Traffic Control (ATC) and is what Ramsey describes as a “significant improvement over legacy radar technology.” ATC can filter what they don’t want to see on their displays, such as low-altitude drones in uncontrolled airspace, but they can see potentially dangerous situations, like a drone on an approach path to a runway, and take action.

Beyond ATC, any other airplane within tens to hundreds of miles around also receives this information, which pilots can use to help determine safe flight paths.

Of course, for it to improve drone safety, ADS-B must be implemented correctly, Ramsey said, which is exactly what uAvionix intends to see happen.

Common objections

There are various objections to using this technology for drones, and one of them is it’s simply too big, according to the blog. Fortunately, that isn’t the case anymore, with uAvionix offering products that range from 5 grams to 70 grams. Others say the technology is too expensive, but the price will start to come down as there’s more demand for the solution, Ramsey said. And when prices come down, more pilots will equip their airplanes with ADS-B (it’s not a requirement for every airplane or helicopter).

Some also think LTE/5G will offer a better solution for tracking drones. While Ramsey agrees these technologies will have a critical role in connecting drones in the future, getting there could take years. As the number of drone flights continue to rise, we need a solution that works today and that can be adjusted as more drones fly in the airspace.

The real challenge

Ramsey describes these as all fairly trivial arguments. Here’s what he sees as the more complex challenge, according to the blog:

“If all the drones that are predicted broadcast ADS-B – there would be so many ADS-B messages bouncing around the skies that it would flood the airwaves and the whole system would come crashing down and be unreliable.”

While that’s true, and is what concerns the FAA and other regulatory bodies the most, there are a lot of assumptions in that statement, Ramsey said. First, not every drone will broadcast to ADS-B. The technology should be limited to risky drone operations, he said, such as flying beyond visual line of sight in controlled airspace. With that limitation, none of the drone operations conducted under Part 107 would use ADS-B equipment.

And regardless of what’s predicted, more than 1.2 million drones were sold in the U.S. last year and there were a reported 1,800 reported drone sightings, according to the blog. That means we need to find a solution to make UAS flights safer today and that can be adjusted as the number of drones taking to the skies continues to grow.

Now let’s talk about how “it would flood the airways.” In the blog, Ramsey points out a recent study that suggests there is a nominal transmission power output between 0.01 and 0.1 Watts that, when coupled with limited drone traffic densities, can result in a compatible operation with the system as a whole. It wouldn’t flood the airways or crash the system if implemented on drones performing risky flights, but would give other aircraft the ability to see those drones from 1-5 miles away on their cockpit screens, increasing safety.

Is it possible to build one that small? Yes, in fact uAvionix has done it, but it isn’t that simple. Why? Technical standards written years ago didn’t factor in drones, Ramsey said, and standard power ranges were set at 7 Watts to 350 Watts. So while there is a solution that could very well work today, we’re just not able to use it.

“It’s not legal to transmit at low power settings that would prevent the very thing everyone fears,” Ramsey said in the post. “So here we are. A technical solution is among us that increases safety today. …But while it is legal to broadcast ADS-B from drones today from 7-350 Watts – contributing to “flooding the airwaves,” it’s literally illegal to broadcast at a power setting that still provides the safety margins needed, but at a comparatively minuscule power setting that preserves the integrity of the whole system.”

Ramsey hopes regulators will see ADS-B as an opportunity to improve safety measures, developing a standard that can be “developed, released, and required on those most risky of drone operations.”

To learn more about uAvionix, its products and what the company is doing to help make drone flight safer, visit uavionix.com.