There is palpable excitement within the unmanned aircraft industry about the opportunities opening up now that restrictions on commercial drone flights are being relaxed.

One sector is moving quickly to adapt to the new landscape: pilot schools. Not only will the Federal Aviation Administration’s easier-to-live-with Part 107 rules unleash drone service firms—firms whose growth could boost the demand for skilled operators—the new rules will make training that next generation of pilots easier to do.

Like firms using unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) for mapping, filming and inspection, pilot schools have long been considered for-profit drone operators and have been working under the same sharp flight limitations as everyone else.

“To provide that type of training, that is considered a commercial operation—because we’re charging tuition for those operations,” said Kurt Carraway, executive director of Kansas State Polytechnic’s UAS program, based in Salina.

Now, however, schools that have been relying heavily on simulators are redesigning their curricula and creating new classes to give students more hands-on experience with multi-rotor and fixed-wing drones. Though flight experience is not required under the new rules, it could be a competitive advantage—especially for those seeking jobs at firms using commercial-grade aircraft and high-end sensors.

“Part 107 facilitates the appetite for professionals,” Carraway said.

Kansas State Polytechnic

Kansas State has been offering hands-on training to students through a Section 333 exemption from the FAA—the first school to do so. Once Part 107 comes into force, the school will offer even more options.

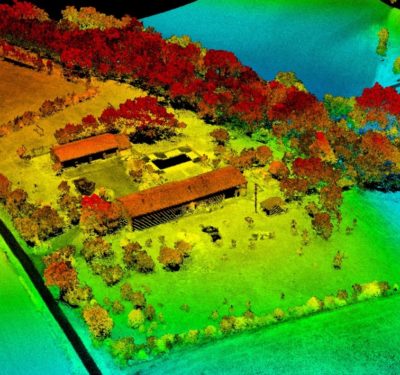

Students will be able to take one of two tracks: aviation technology, which focuses on the operations side of UAS, and engineering technology, focusing on integrating sensors and systems. But even in the aviation track students will develop skills that go well beyond operating a joystick or setting waypoints. Carraway said graduates would be trained to identify data collection challenges, determine what aircraft and sensors are needed to solve the challenges, integrate those sensors onto the aircraft, and ultimately fly the UAS. They also will understand the current safety and regulatory landscape and how to interpret and optimize the data they get back from their vehicle.

The new curriculum, available starting with the 2016–2017 academic year, begins with incoming freshman getting a private pilot certificate for manned vehicles, and then also becoming certified to fly by instruments only. By the end of the first year they also will have taken a course on flying multirotor vehicles in which each student flies about 40 missions for a minimum of 10 hours behind the controls.

By sophomore year, those same students will be teaching underclassmen how to fly.

“Without a doubt, [being able to teach others] is one of the things that our industry partners have…expressed is a requirement. When they’re hiring a UAS professional, they want pilots that can instruct,” Carraway said.

Not only does hiring a good teacher mean that one pilot can quickly become two or three, but able teachers are good communicators.

“To be able to communicate and articulate what aircraft can do and what they can’t do, be able to sit down and talk to the end users and understand what their requirements are—folks that have a strong background in instruction are able to do that very effectively,” Carraway said.

By the end of their sophomore year students will have flown fixed-wing vehicles for about 20 hours each and by the end of junior year they’re qualified to teach others to fly every vehicle in Kansas State’s fleet—more than 30 different kinds. The last year of the program is devoted to advanced applications, assembling aircraft, and data processing.

One change with Part 107 is that students from outside the UAS major will get an opportunity to fly, though Carraway said that opportunity would be limited to multirotor vehicles for now because they’re much simpler. Kansas State’s 333 exemption was written to allow only students with a pilot’s license to fly UAS, but now students in other programs, like engineering, can try their hand at flying as well.

The university is also developing an intensive course for professionals who want to use drones but don’t necessarily want to become professional pilots: think real estate photography and the like. This five-day course would bring in complete novices, drill them in the essentials of safety and regulations over the first three days, help them pass the FAA’s UAS written test (see Part 107 Requirements for UAS Operators, page 38), and give them about a day and a half of flight training with a multirotor.

“That’s not going to approach the skillset that our degree-holding students will have,” Carraway said, but it would give attendees a foundation in the basics and open up their career options.

Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University

Each of Embry-Riddle’s campuses—in Daytona Beach, Fla., Prescott, Ariz., and Singapore—offers training with UAS. But if you want to fly, Daytona Beach is where you want to be.

The non-profit school began offering a UAS minor in 2009, said John Robbins, Unmanned Aircraft Systems program coordinator. By 2011, the program had expanded to a major with eight people enrolled. By spring 2016 there were 243 students enrolled.

“It’s one of the fastest growing programs on campus,” Robbins told Inside Unmanned Systems.

The curriculum starts with the very basics including the history of unmanned vehicles.

“Then we go into the more technical stuff: remote sensing, engineering, computer science, and some support classes we felt were necessary for a broadened individual coming out [of school],” Robbins said. “They can be an operator, a field tech, a project manager” or more.

Up until Part 107, the school used a lab with 16 simulators designed to replicate the experience of flying a generic medium-altitude, long-endurance, fixed-wing vehicle. “We could [train] a pilot, or a sensor [operator] or we could put a pilot and sensor operator together to work it through,” Robbins said.

The school did have a 333 exemption, but the way it was written didn’t allow for student flight training.

Simulators are fairly well suited for UAS training; even a pilot of a real UAS is often just looking at a screen.

“But when it comes to things like data collection, in-the-field maintenance, or physically prepping the aircraft to fly,” Robbins said, “these are all things we can do now.”

The university also hopes to offer more hands-on flight time, including experience operating senseFly eBees and other multirotors. They also use Latitude Engineering’s HQ-40s, a hybrid quadcopter with VTOL (Vertical Takeoff and Landing) capabilities.

“We’re still developing that into the curriculum,” Robbins said.

Embry-Riddle is also setting up a new outdoor flight facility that will complement the fieldwork that the school already does—using drones, for example, to monitor beaches for wildlife conservation or emergency management.

Students will get about 20 hours of flight time from each class they take, plus use of the school’s labs.

One thing that’s not changing: Embry Riddle students are still going to be required to get certified to fly manned aircraft.

“We feel the ratings are necessary even though not required to the same extent,” Robbins said. “When you operate larger aircraft, many companies are requiring a manned certification.”

University of North Dakota

The University of North Dakota in Grand Forks has just cut the ribbon on its latest source of pride: a dedicated building for its expanding UAS program. In addition to lab and classroom space, the cornerstone of the $22 million building is a two-story indoor test flight obstacle course through which students will need to fly a small helicopter.

Prior to opening the new building, instructors created jury-rigged obstacle courses “of PVC pipes and hula hoops,” said Beth Bjerke, chair and professor of the aviation department.

Indoor flight was the only kind of training UND was allowed to offer until implementation of Part 107. Students trained with DJI Phantoms in the PVC and hula-hoop flight arena. They got more indoor flight experience as part of a course where they assembled their own small quadcopter—with exact flight hours determined by how well they built the copter, lead flight instructor Erin Schoenrock said.

Students also received heavy simulator training—70 hours in a ScanEagle simulator.

UND won’t be removing the simulator component, and in fact it is adding a Predator simulator so students can get experience flying multiple vehicles. Starting this fall, however, UND also will provide actual flight training outdoors on fixed-wing vehicles (the exact hardware is still being determined).

The university prides itself on one non-flight-related part of its curriculum: computer science. After recently reaching out to UND alumni and their employers, the consensus was that a greater grounding in programming, especially networking and cybersecurity, would be helpful to new grads. Now students take an intro to computer science course alongside CS majors to learn “some of the basic thought processes you might see,” Schoenrock said

They also will be required to take a class on cybersecurity.

“If you’re collecting data, you need to be concerned about security,” Bjerke said.

Oklahoma State University

Oklahoma State University’s UAS program is offered at its Stillwater campus. The first school to focus on UAS engineering at the graduate level, OSU’s program also offers engineering specialties to undergraduates and a pilot track with a UAS minor.

Gary Ambrose, OSU’s director of strategy and applied research at the Unmanned Systems Research Institute, said the school is currently “in the process of writing a new curriculum that accommodates non-pilots.” Currently most of Oklahoma State’s UAS students have their manned private pilot certificate, but it won’t be a requirement going forward.

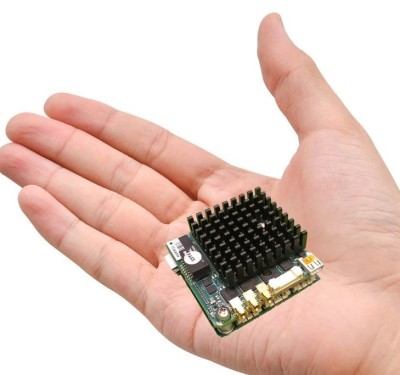

The fixed-wing platforms that OK State will begin using in the spring of 2017 will all be Group 1, the smallest class of UAS.

“We’re thinking about using Skywalkers and Bixlers,” Ambrose said.

Whatever they choose to use, Oklahoma State is hoping to ramp up quickly.

“Just internally, we are at a shortage of fixed-wing UAS operators,” Ambrose told Inside Unmanned Systems. A recent research projected forced the school to “juggle pilots” because they only had five or six who were qualified to fly. “That’s why we’re designing these courses—to generate more fixed-wing pilots.”

The new courses will incorporate a lot of simulator time, hands-on landing and takeoffs plus emergency procedures.

There are still some kinks on the research side to be worked out; currently, Oklahoma State is assisting DOD with swarming-related research. Part 107 doesn’t prohibit swarming, but requires one pilot per vehicle, which would make swarming fairly prohibitive.

“We just need to clarify some of that within our Certificate of Authorization,” Ambrose said.

The program is growing. Many students in the manned pilot course “are starting to see the market grow for unmanned” and switching tracks, Ambrose said. Many of them, those who are qualified to fly, he said, are being pulled out of school to fly missions for some of the university’s partners, giving them valuable real-world experience before they graduate.