Europe was an early-rising bright star in the drone industry and it continues to shine. The continent now needs to move quickly to stay ahead of the game, but an EU-wide regulation framework for drones, it would seem, is still years away.

Speaking at the Commercial UAV Expo in Brussels, European Commission (EC) representative Koen De Vos told attendees and the world that they will have to wait at least two more years for a drone regulation that covers the whole of the European Union.

De Vos, whose General Directorate MOVE is coordinating the EU RPAS regulation initiative, compared the rapid rise of the drone industry to the move from horses to cars, and said, “This is quite disruptive – disruptive for industry, disruptive also for regulators.”

And disrupted is what EU regulators appear to be. To be fair, the Commission and EASA, the EU’s aviation certification body, have done their parts, delivering a proposal for a new European Aviation Safety Regulation, including key provisions for drones, more than a year ago – delivering it to the European Parliament and European Council, that is, where the proposal has languished ever since.

According to EU procedure, the Parliament and Council must debate, amend and adopt any proposed rules, establishing EU competency in the area in question, before those rules can come into force. Last year we reported on expectations that this part of the process would be completed by early 2017. Now the “hope” is that it will happen at the end of 2017, which would then push the actual implementation of a new regulation into 2019, at the earliest.

What everyone knows

De Vos laid out the rationale for a pan-EU regulation: “Under the current regulatory framework, drones under 150kg are governed by the individual EU Member States. But we don’t want you to have to deal with 28 national rules. Even if you want to work in a small niche market, you may want to work on a European scale. If you want to film in London, you might also want to do it in Berlin, or Paris or Brussels.”

So there is an immediate European dimension, De Vos argued, not only for European drone manufacturers but also for service providers and final clients. “If end users can have access to a Europe-wide supply of drone service providers, the prices for these services will fall.”

The EU regulation currently under debate is based on the recommendation of the EC and EASA, developed around an ‘operations-centric’ concept that focuses on how a drone is to be used rather than on its physical characteristics.

“This is a set of rules that are proportionate and risk-based,” De Vos said. “In other words, safety requirements are set in relation to the risk an activity poses to the operator and to third parties, meaning the general public; the greater the risk the more stringent the requirements.”

De Vos confirmed the proposal is still on the table at the Parliament and the Council. “They are still discussing it in the framework of a wider review of the safety rules.

“We had hoped that the Maltese would get an agreement. We now hope that it will happen under the Estonian Presidency,” De Vos said, “that we will get a political agreement to establish EU competence on smaller drones at the European level. Then we can come forward with a coherent European regulatory framework.”

We spoke to De Vos after his presentation, when he explained, “In Council you typically have the Presidency that wants to really make the best out of it, they want to achieve some visible success, and right now the RPAS regulation is one of the few things in the pipeline.” Thus, the expectation was that the Maltese Presidency would be eager and quick to move forward.

But, De Vos said, “The Maltese did not succeed. They were confronted with a tough negotiator in the Parliament, MEP Marinescu, who is an aeronautical engineer and who knows what he is talking about; he could delve into details and the Maltese didn’t know how to deal with it.” Marian-Jean Marinescu is Vice-Coordinator for Transport and Tourism at the European Parliament.

“Now we hope that under the Estonians, the next six months, they will come up with a nice negotiating team and they will be good. So we expect a political agreement before the end of the year under the Estonian Presidency.”

Again, the discussions at the Parliament and Council are only aimed at establishing the EU’s competence to rule in this area.

“That will concern only the question of competence,” De Vos said, “and then we, the Commission and EASA, have to come back into it. Once the Union has got this new competence, then we can move to adopt the EASA rule and it becomes a Commission regulation and a European law.

“But first we will have to put in place the legal requirements to provide a whole ecosystem, the whole framework. What about the ‘U-Space’ system [see below]? To keep operations safe, we have to adapt our airspace rules, we have to introduce some major operational rules.”

So the bottom line for the Commission is there is still more work to do. “By 2019 we want o have all the legal bases in place,” De Vos said.

U-Space

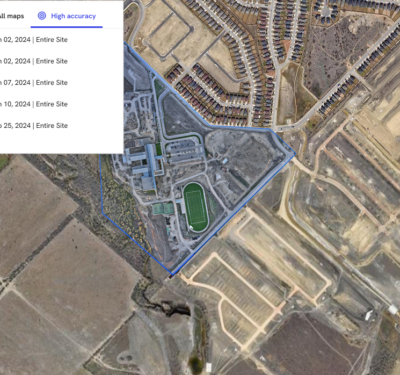

While the Parliament and Council have been mulling over questions of European competence, the EU-funded Single European Sky ATM Research Joint Undertaking (SESAR JU) has been working on a new air traffic management concept for commercially operated drones. The system, called U- Space, is aimed at enabling complex drone operations with a high degree of automation in all types of environments, particularly in the urban context.

According to the SESAR JU blueprint, unveiled this month (June 2017), the new system will enable a wide range of drone missions that are currently restricted. U-Space is described as featuring an online registration system, flight planning and flight approval as well as tracking, recording and playback capabilities for civil and commercial drone operations.

“U-Space will not be air traffic controllers sitting in front of screens looking at all the drone operations,” said De Vos. “It will be an automated system where we try to organize all the information on location, on the technical capabilities of the drone, how fast it can fly, how high it can fly, of other air traffic, so that highly automated or autonomous drones can operate.”