LSUASC Flood Response

On May 25, Wimberley, Texas, was devastated by heavy flooding along the Blanco River. The flood waters destroyed more than 400 homes, and four people in Hays County lost their lives.

The team from The Lone Star Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Center of Excellence and Innovation (LSUASC) at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi was called in as part of the recovery efforts, and asked to conduct low-altitude research flights to help find missing people, livestock and vehicles, Chief Engineer Jerry Hendrix said.

The three-person team traveled to Wimberley, 30 minutes southwest of Austin, on two separate occasions. They were on site for a total of about two weeks, and flew 18 missions.

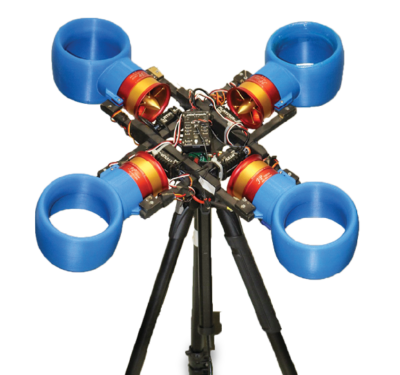

They worked with various UAS including the AscTec Falcon 8 provided by HUVRData of Austin; a senseFly eBee provided by Urban Engineering of Corpus Christi; and a DJI Phantom quad-copter provided by A&M-Corpus Christi’s iCORE Lab and the University’s College of Science and Engineering.

This was the first time the LSUASC test site was part of a disaster response, and Hendrix said they learned a lot from the experience. Here’s a look at some of those lessons learned, and how drones can be helpful after a natural disaster.

Be Prepared

The most important thing Hendrix and his team learned is you have to be prepared when flying these types of missions. That includes making sure your equipment is functional, and that you have a logistical inventory of all your equipment before you’re deployed. It’s also important for everyone to have emergency business-sized contact cards with local information, team member cell phone numbers and other contact information.

They brought along all their important paperwork as well, including their Certificate of Authorization from the FAA and appropriate pilot information, Hendrix said. The team made sure to dress appropriately, in orange vests and orange hats that identified them as part of the search activity, and didn’t go into the search area without snake bit kits and first aid kits in case anyone was injured.

While planning for the environment is key, Hendrix also said you need to be prepared for the unexpected and brace yourself for the devastation you’ll see.

“It’s an ever changing environment. In this case it was a flood, so we were dealing with receding water and a lot of debris. The experience itself can be rather shocking,” he said. “It’s very solemn. You know there’s loss of life involved. You’re looking through people’s belongings, parts of automobiles, housing, roofing, clothes. There were debris piles as large as 10 or 20 feet in width, 10 or 15 feet in diameter and that went on for hundreds and hundreds of yards. You spot all kinds of things as you fly the aircraft.”

You Have to Communicate

During a search and recovery operation of this size, you have to work closely with whoever is in command to coordinate flights, Hendrix said. Manned aircraft were part of the effort as well, and without the proper coordination there could have been near misses. Hendrix and his team operated under the air boss, who was responsible for coordinating all flight operations in the area to support response to the flooding. They worked with first responders, Texas Task Force One, multiple incident commands, and even dog team.

Many volunteers also came out to help search for their loved ones, and it was important to coordinate with them as well, Hendrix said.

“We had a few people show up to fly UAS uncoordinated and that caused confusion,” he said. “We were also dealing with a crowded search area with first responders and a lot of volunteers there on behalf of their families. There was a lot of interest and a lot of help, but we had to be careful in coordinating work with these individuals.”

Communicating with land owners was also key to completing these missions, Hendrix said. They had to get permission before operating on anyone’s property, and that meant talking with land owners about what they were doing and why. They were fortunate enough to have a liaison from the community to help with these conversations.

Communicating among UAS team members also proved to be challenging during these missions, Hendrix said.

“We were dealing with a winding river,” he said. “We had to put lookouts and visual observers with orange vests at key points along the river. We had hand signals we used to notify operators of certain situations, like if a manned operator was coming around the corner.”

Be Ready to Make Adjustments

Operating UAS in a disaster-stricken area is much different than operating from a test site. During their time in Wimberley, the LSUASC team had limited places to launch and recover their UAS. Transporting their systems in and out of the area was also a challenge, and washed out roadways meant it typically took them a few hours to get to search sites across the river, even though they may have only been 100 yards apart.

“You might be launching the aircraft from an area that’s not the most optimum,” Hendrix said. “For example we had to modify one of our procedures to allow us to catch the quadcopters we were using. There was no level ground to land them on.”

Normally, they operate UAS above line of sight, but because the river basin was several hundred feet below them, they found themselves operating at a line of sight they weren’t accustomed to, Hendrix said. They had to do some on the job training to make it work, but once they did they were able to get into areas that manned aircraft simply couldn’t because of the swiftness of the water.

“The manned aircraft couldn’t get into the tight areas we could get into with the smaller UAS,” Hendrix said. “UAS are well suited for this type of mission.”

What They Found

Every day, the LSUASC team would get a Google map with pinpoints of where they were to operate, Hendrix said. They’d collect and review data, and sent several areas back to incident command, who would then send people to take a closer look. They found trucks, parts of motorcycles and other debris, but didn’t locate any missing people through their efforts.

Hendrix said the team was called in several days after the actual event to support search efforts, but in the future he thinks tests sites like LSUASC should be part of the first response team in disaster situatuions. If they can get on site within hours after the event, UAS can be a lot more beneficial to the search efforts.

Hendrix is proud to have been part of the team at Wimberley, and hopes to help with more efforts like this in the future. The team will continue to train and prepare for these types of important missions, missions that can potentially save lives.

“It was an honor for us to support the state in that fashion,” he said. “It’s not something that everyone can do. It’s not for the hobbyists or general public to operate in those areas. You need training and a certain background to do that. The challenges are navigation, coordination, communication and making sure you have the right assets.”