Good timing makes everything easier. This January the new Advisory Committee on Automation in Transportation (ACAT) held its first meeting the day before the start of the U.S. Conference of Mayors, a scheduling coincidence that may end up benefiting both.

Good timing makes everything easier. This January the new Advisory Committee on Automation in Transportation (ACAT) held its first meeting the day before the start of the U.S. Conference of Mayors, a scheduling coincidence that may end up benefiting both.

Launched by the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) just before the Obama Administration handed over the reins, the ACAT was chartered to gather information and develop technical advice to “foster the safe deployment of advanced automated and connected vehicle technologies.” DOT will look to them for recommendations to guide federal policy.

The scope of their work, however, reaches far beyond the passenger cars that have captured so many imaginations. ACAT, according to that charter, is also to look at the policy and technology of “enhanced freight movement technologies, railroad automated technologies, aviation automated navigation systems technologies, unmanned aircraft systems, and advanced technology deployment in surface transportation environments.”

Moreover, their charter specifically directs them to look past the immediate future at “emerging or ‘not-yet-conceived’ innovations to ensure DOT is prepared when disruptive technologies emerge.”

“We recognize how much transportation technology is changing and evolving,” then Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx told the group, emphasizing that theirs was a multimodal mandate. “It’s not just cars—it’s everything. And our goal is to figure out what lines of symmetry exist between different modes of transportation in this area that we can work from as a department, but also to think about second, third and fourth order impacts of automation.”

That’s a tall order but DOT has chosen 25 people from a noticeably broad range of perspectives. There are representatives from firms of all sizes working on driverless and driver-assisted vehicles such as super-rail.

But it’s not all business. Nearly half the members are technology and policy experts, people representing insurance and labor interests and those with an insight into safety including Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger. (See a complete list of members on page 38).

Perhaps most importantly, ACAT’s membership includes two mayors: Mick Cornett, the mayor of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and Eric Garcetti, the mayor of Los Angeles, California. Garcetti, whose city is legendary for its traffic, is one of ACAT’s two co-chairs.

On the Front Line

Mayors will likely have a huge role in fueling—or hampering—the adoption of automation and driverless cars because urban areas, experts say, will be among the technology’s earliest and biggest adopters.

“Autonomous vehicles’ initial application will really be in the cities,” said Bill Ford, the executive chairman of Ford Motor Company, “because this is where you have huge congestion problems.”

It was these local politicians who Ford addressed at the annual U.S. Conference of Mayors just two days after the ACAT gathering. He was interviewed during a plenary session by Cornett, who is not only an ACAT member but also the head of the conference—a position he has been using to educate his colleagues about the possibilities and potential pitfalls of driverless cars.

“One of the topics I wanted to get deep into this year as your conference president is the introduction of autonomous vehicles,” Cornett told the packed ballroom as he introduced Ford.

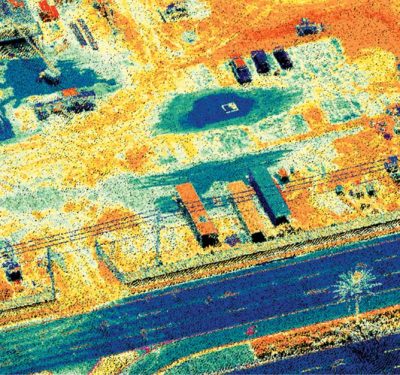

Image courtesy of General Motors

Pros and Cons

Ford described how autonomous technologies could change future cities, including making them more open because there’d be less need for parking.

“You’ll see drones going overhead,” Ford said. ‘”Wearables—we will all be wearing things that will monitor how we’re moving and where we’re going to. Everything will be on one network, pedestrians, all forms of transport—all talking to each other. You’ll have charging hot spots all over the place.”

If we get this right, he said cities will have better air quality and be much greener as well as safer for people and vehicles. And people will still be able to get around.

“A clean traffic jam is still a traffic jam,” he said. “We could clean everything up and still not be able to move. The goal is to do both.”

Jeff Speck, who was invited to speak to the mayors the following day, was less sanguine about the promise of driverless vehicles.

He suggested the mayors needed to be savvy about the pros and cons and clear-eyed about what they want for their cities. For example, he said, if you ease the pain of traffic delays, you will likely energize urban sprawl.

“Cities that want to avoid the long-term balance-sheet burden represented by low-density suburbia must double down on efforts to promote smart growth, which essentially means eliminating all hidden subsidies for sprawl,” he wrote in a handout for attendees.

Transit, he said, could run more smoothly, however, if the cities had access to the data gathered constantly by the new AVs. Speck urged mayors to consider a collective effort to make sure data sharing became a precondition for AV licensing.

He also told the audience they needed to be realistic about how long it will take for the technology to be adopted and at what point it would become useful in addressing problems.

Even so, he has no doubt autonomous vehicles will be an element of the future, he said.

“New technologies that increase convenience are unstoppable,” he told the mayors.

First Steps

Some of the issues raised by Speck were already on Co-Chairman Garcetti’s mind when he addressed the ACAT for the first time.

“We need to anticipate the effects of self-driving cars on our already overburdened streets and freeways and decide how best to curb urban sprawl,” he said. “We don’t want people commuting even longer to work—even if their hands aren’t on the wheel.”

Co-Chairman Mary Barra, General Motors’ chairman and CEO, said her industry was in the midst of “more transformation than has occurred in the last 50 years,” a change with profound implications for the country.

“The vehicle technology,” she said, “coupled with advancements in complementary technologies like vehicle connectivity and electrification, have the potential to not only transform the way we get from point A to Point B but frankly the way we live.”

Garcetti suggested a light regulatory touch was the way to foster such innovation and that cooperation between local governments and technology firms—like the work his city is doing to gather and share data with companies—could inform both. “I think nobody understands the benefits and challenges of this technology better than local government.”

A number of members endorsed the idea of a light touch, stressing that firms need to be free to innovate and test out their ideas.

“I think it’s very hard for a large committee to make detailed engineering trade-offs in order to figure out how to maximize for safety,” said Keller Rinaudo, CEO of Zipline International. “Another approach might be to figure out how we can encourage experiments at a small scale across the U.S.—in Obama’s words ‘Let a thousand flowers bloom’—and then scale and spread those technologies that offer the biggest safety and customer benefit.”

Zipcar’s Robin Chase summarized the issues raised during the meeting as falling into four “buckets” for future action—experimentation and prototyping, harmonization of federal, state and local regulations, safety issues, and the impacts that will come from the adoption of automated technology.

Perhaps no one brought home the complications on the horizon better, however, than Delanne Bernier, vice president of government relations for the Automotive Recylers Association.

Speaking during the public comment period, she raised the question of what happens when it comes time to junk this new generation of vehicles. Many people are unaware, for example, that the batteries in electric cars may require special handling. “Some people have left lithium ion batteries out in fields and they blow up two weeks later,” she said.

Even though this technology is only just emerging, regulators need to consider now what to do both practically and environmentally when it comes time to replace an electric vehicle or a driverless car, she suggested.

“There is a fairly standardized way of dismantling end-of-life vehicles and handling them,” Bernier said. “What about the future for new technologies?”