Over the last few years, drones have become critical tools at Chevron facilities. Simply put, they’re changing the way work gets done, and that translates into enhanced efficiencies, reduced risk and significant cost savings.

The oil major deploys UAS for various applications, from the flare stack and tank roof inspections that have been mainstays since the program’s early days to capital project management, live broadcast emergency response, leak detection, environmental remediation, and pipeline-right-of way and security, to name a few.

“Every few months, we find more interesting and useful ways to use the technology,” said Larry Barnard, DS&C operational governance, unmanned systems. “Manufacturers are coming up with a better variety of sensors that can be deployed on these platforms, and that really expands the use cases.”

Barnard, who is an advisor for the Chevron Unmanned Center of Excellence, works at the El Segundo Refinery in California, which is home to the company’s first in-house drone program. Payloads flown include high-res cameras and video, infrared cameras, LiDAR and environmental sensors. Drones are deployed several days a week, and Barnard expects use to continue to increase as the technology advances and working groups gain a better understanding of its benefits.

And that’s the story across the industry. Larger companies are scaling programs and developing UAS groups. Rather than keeping UAS siloed, they’re sharing information, best practices and resources throughout organizations, allowing the technology to have a greater impact. Even with the COVID-19 pandemic, which lowered oil prices and slowed the industry earlier this year, drones are still part of the plan to innovate, providing needed remote solutions in a time when travel is restricted.

“The community is looking beyond use cases to actionable data and ROI,” said Sean Guerre, executive director of the Energy Drone and Robotics Coalition. “In the early days, it was more around individual use cases, field trials or proof of concept. Those are still going on to evaluate new ways to do things, but there are so many proven applications they’re now trying to scale.” (For more on the coalition’s work, see “Five Good Questions” on page 66.)

There’s still more potential to be unlocked and challenges to overcome, but, after initially slow adoption in an industry that’s known for being conservative, oil and gas is starting to embrace drone technology.

LEAK DETECTION

One of the biggest drone applications in oil and gas is identifying gas leaks, particularly methane, said Tyler Collins, VP of energy solutions for Raleigh, North Carolina-headquartered PrecisionHawk. Government emission regulations, along with shareholder and market demands, have put pressure on the industry to find emissions and their sources as early as possible, minimizing environmental impacts.

To perform these inspections, PrecisionHawk drones are equipped with a visual camera, optical gas imaging sensor (OGI) and a methane detection laser. The OGI sensor is similar to a thermal camera but can locate specific gases, such as methane, that are invisible to the naked eye. The camera shows where the leak is once it’s identified, while the laser determines the type of gas leaking and its concentration.

Rather than walking a well pad or a pipeline armed with a sensor to spot leaks, a time-consuming and dangerous task, personnel know exactly where to go to make repairs and which are priorities.

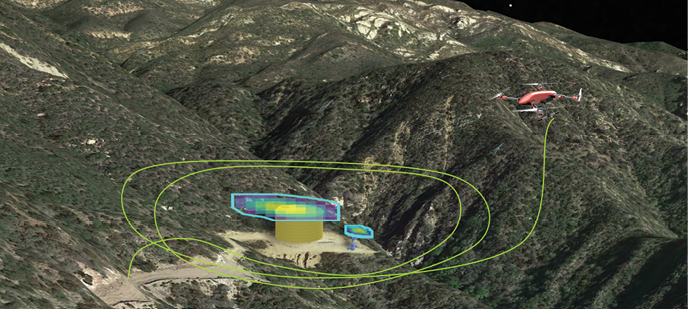

Austin-based SeekOps created a sensor that maps out methane emission in 3D space and combines it with imagery, giving users a holistic inspection, said Andrew Aubrey, senior VP of strategic partnerships.

“We use data analytics and also process a 3D point cloud and turn it into a leak location and leak rate,” Aubrey said. “We turn that 3D point cloud into a pin on a map to indicate a natural gas or methane leak, and then tell how much is being lost.”

The sensor can be placed on any platform, Aubrey said. Once the drone collects the information, it’s uploaded to a cloud system and run through algorithms. In one to three days, clients have the information they need to make necessary repairs, prioritizing by volume loss rate.

The sensor can be placed on any platform, Aubrey said. Once the drone collects the information, it’s uploaded to a cloud system and run through algorithms. In one to three days, clients have the information they need to make necessary repairs, prioritizing by volume loss rate.

Many clients are going beyond the requirements and flying as often as quarterly or monthly to detect leaks, Aubrey said. The attention is on more than looking for leaks, but also on taking measurements that help back up the emission reduction oil and gas companies are emphasizing.

“More measurements make for better understanding and a better chance of spotting anomalies,” SeekOps CEO Ian Cooper said. “We’re seeing a move toward more frequent measurement and, eventually, continuous.”

Jonah Energy started a drone program about two years ago, with the purpose of increasing efficiency and effectiveness in methane leak detection, said Paul Ulrich, vice president, government and regulatory affairs. Headquartered in Denver, the company operates a field in Wyoming that’s about 50 square miles; instead of someone driving from location to location, a centralized operator can fly a drone to determine if there are leaks that need to be addressed.

The drone flies a FLIR OGI sensor over an area that’s producing natural gas, and if a leak is detected the operator may fix it immediately or generate a ticket to dispatch someone right away, vastly enhancing the company’s reaction time.

Near infrared cameras can help identify leaks by looking at vegetation too, said Don Cummins, president of Air Data Solutions, with vegetation stress near a pipeline an early indication of an underground leak up to two weeks before signs become visible. The company maps hundreds of thousands of acres per month for midstream clients, applying findings to change detection and route planning. The Natchitoches, Louisiana, operation also flies drones to visually look for leaks and other threats to a pipeline, such as vegetation encroachment.

EXPANDING USE CASES

While leak detection has become a popular oil and gas application, the industry is finding many other ways to benefit from the technology. Chevron, for example, deploys drones for internal equipment and asset inspection, earthworks mapping, project progress monitoring and environmental applications, Barnard said.

Flare stack and oil rig inspections represent early uses, Collins said. Drones allow personnel to complete the same inspections they’ve done in the past, but without shutting down equipment or erecting scaffolding. Once defects are identified, workers know exactly where to go to make repairs, again minimizing downtime.

Environmental use cases are starting to gain traction as well. For example, Chevron has a facility in Australia on a nature preserve that uses drones and RFID tags to track turtle migration and nesting in support of its operating permit, Barnard said. As another example, they use an AeroVironment Quantix fixed-wing VTOL for vegetative analysis on remediation sites after native-species replanting.

Jonah Energy deploys drones to evaluate and assess total acres of reclaimed areas. “Jonah takes enhancing habitation and reclaiming as fast as we can very seriously,” Ulrich said. “Drone technology allows us to capture acres disturbed and reclaimed and address acres we need to reclaim in a much more efficient manner.”

Drones also have a place in pipeline route planning, Cummins said. Air Data Solutions supports engineering companies with route planning services, coordinating with land surveys to provide imagery and LiDAR of proposed routes. Imagery, mapping and terrain models speed up and reduce the cost of preliminary surveys.

LiDAR allows them to see through vegetation, Cummins said, while also creating a more accurate terrain model.

“We leverage high-resolution aerial imagery and load it into a geospatial program to put together assessments so clients can construct a pipeline from point A to point B,” said Wesley Alexander, director of strategy for TMI Solutions. “Drone-based LiDAR assists in the design and can be used in mountainous areas where you worry about slippage when laying pipe, where you might have landslides that disrupt the pipes.”

Once construction begins, drones routinely fly prescribed patterns around a site to show how it’s changing, Cummins said. This not only documents what happens, it’s a way to provide information to site managers without them having to be there, something especially useful during the COVID-19 pandemic.

These systems also can give insights into what’s going on underground. Sensors can identify if root systems are interfering with pipelines, for example, said Jon Berry, business development director for AeroVironment. Magnetometers flown on a drone during the exploration phase can identify signatures in the rock that lead to areas that should be investigated.

Jonah Energy invested in three smaller drones to map buried ground utilities to help avoid line strikes, Ulrich said. The ability to create CAD drawings of new facilities also has been critical to enhancing efficiencies. Then there are equipment counts for accurate inventory, soil management—which entails measuring soil piles for a more effective response to clean up during a spill—and deploying drones for evaluation during an emergency.

“If we have a major incident of any type, such as a fire or a well blowout, we use drones to take a look, keeping our employees and first responders out of harm’s way,” Ulrich said. “That allows us to effectively get a detailed account of the incident and formulate a proper response.”

INTERNAL INSPECTIONS

Drones, as well as ground robots, are deployed for confined-space inspections. Getting a person inside these spaces might require removing product, cleaning hazardous chemicals, or using scaffolding or ropes. Robotics eliminate many if not all of these steps, reducing risk while also saving time and money.

There are cases when a ground robot might make more sense than a drone, such as when the tank that needs inspected has liquid in it. But if the tank is empty, the better tool is a collision-tolerant drone that can fly in GPS-denied environments.

“Using a drone can significantly reduce downtimes for assets like boilers and pressure vessels, allowing them to get back online quickly,” said Zacc Dukowitz, who’s with Flyability’s marketing department. “Drone inspections also produce high-quality visual data, which can be referred to at any point in the future as a record of the condition of the asset over time, creating greater efficiency in the maintenance cycle.”

Flyability’s Elios 2 drone sits inside a fixed cage and has a collision-resilient flight algorithm and motor controllers, helping it to fly in confined spaces, Dukowitz said. It also has oblique lighting so live feeds show the texture and depth of the objects inspected, as well as a stabilizing feature that allows for complete asset coverage. The 4K camera, which is outside the protective cage, can identify tiny cracks and fissures and provide live HD streaming video.

At Chevron, Barnard uses the Elios 2 for a variety of equipment inspections, including in dense, dusty environments. Before flying the Elios, operators must understand the internal environment and make sure it’s safe to deploy. Beyond detecting analomies, findings might indicate they can forego a planned task during a shutdown, such as a chemical wash, reducing unnecessary downtime.

DATA, DATA AND MORE DATA

As payloads grow in sophistication, integrating multiple sensors, the data collected is improved, but there’s also more of it to process. And that data often needs to be seen by multiple people, who may not even be in the same country. Finding ways to efficiently store, transfer and analyze all that data is critical. Many are using cloud-based systems for storage, but some clients prefer more old school transfer methods, such as SD cards.

When it comes to analysis, it’s not feasible to have an engineer sort through thousands of images, which is where artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning serve as difference makers. These technologies can vet the data, find the analomies and then allow human expertise to determine which repairs are immediate and which can wait.

AI must be taught how to detect anomalies with accuracy, and that requires large datasets of defects such as corrosion on a tank or leaks in a pipeline. Eventually, the goal is for AI to handle the entire process without being touched by a human.

“If you have a large image database of what leaks look like and what pieces of equipment look like, you can train AI from that,” Collins said. “Once it’s trained, you can run imagery through AI to confirm this is a leak and it’s coming from that piece of equipment, and you can do that very accurately.”

The software continues to evolve, with companies looking for ways to quickly provide actionable data. TMI’s software, for example, integrates with the drone’s flight controller and annotates as it’s flying, Alexander said. When a picture of a defect is taken, it appears on the control screen along with defect tags. Once tagged, the user has a geolocated image with latitude and longitude of where the image was taken. After the flight, a report is generated with all images and their locations.

Data can also be put into an organization’s software for further analysis and manipulation, whether that’s to create models or take specific measurements.

FACILITY CHALLENGES

As more oil and gas companies opt to create drone programs in-house, which often include service providers as well, personnel must be trained how to fly drones, capture the best imagery and understand the airspace, Barnard said. And the rest of the workforce must be educated on how drones can make their lives easier so the technology “moves up their individual stack of solutions.”

Data security is also critical, with clients uneasy at the thought of sensitive information getting into the wrong hands, Alexander said. Many companies are addressing the issue, and convincing folks who are hesitant to use the technology of its value. With all the successful use cases, that’s getting easier to do.

One of the biggest hurdles remains regulations, particularly for beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) applications. More applications will open up once BVLOS flights are allowed, but it will take time and technology development for that to happen.

WHAT’S NEXT

It’s clear the future is automation. In the next few years, there will be a scaling through different levels of autonomy. Systems will automatically perform pre-programmed flights, and UAS operators who today control one system will control multiple units, both on the ground and in the air. Collaboration between unmanned systems will become more common, leading to even more robust datasets and actionable insights.

Regular BVLOS flights are inevitable, Alexander said, and part of “the next evolution of drones in oil and gas.” Once restrictions are lifted the potential is unlimited, opening up a world where drones can automatically fly three or four hours to patrol 400 miles of pipe, report data to an AI-based thinking machine that’s then fed into a software management system.

“I see autonomy as being the key to unlock the real value,” Barnard said. “If we think about the way we did things before and add creative tech solutions, we’ll come up with more ways to change the way we do work, and that’s what it’s about.”