Ah, the Lapalco Bridge. Built in 1972 in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, the half-mile long span carries numerous commuters and freight deliverers across the Harvey Canal. The double leaf drawbridge—a bascule bridge, to be more formal—opens so numerous barges and container ships can navigate to and from the Mississippi River and the thousand-mile long Gulf Intracostal Highway.

For close to 50 years, Lapalco has provided a shortcut commuters have sworn by. But too often area drivers have sworn at the bridge. They may tolerate both “leafs” tilting to let ships pass, even at unexpected times. They’re less forgiving when the six approach lanes that funnel into four narrow ones on the bridge get clogged, or when ice closes them. Or when mechanisms fail. Or when a water main ruptures and floods streets under the bridge.

Or when things get truly weird and a roosting pigeon gets stuck in a motor and breaks it.

Consequently, a new bridge is envisioned to rise on the north side of the existing structure. Several layers of contractors have been brought on to survey and rehabilitate the current Lapalco and support the new span’s design. The existing bridge “needed work,” said Chad Poche, EVP of BFM Corporation, a Kenner, Louisiana, surveying firm involved in the project. “One: capacity. Two: it was out of service frequently. And it’s just old.”

Using its own Leica Total Station measuring tool and Leica GPS geosystem and a CEE Scope Dual Channel Echo Sounder, BFM could survey the right of way and “the whole hydro several hundred feet on each side for utilities, elevation and profiling.” But additional, nuanced equipment and expertise were welcomed.

Enter Triad Drones, with nimble, small-company solutions on land, in the air and on the water, developed over its year-long existence.

COLLABORATIONS

Triad Drones opened its plant in Tampa, Florida, in January 2019. Though small, it begin offering an array of hardware and software solutions for inspections and data collection. It customizes existing drones and AVs, and produces its own vehicles when dictated by market gaps.

“I’m a drone company, but a lot of companies use me as a technologist, from computer set-ups to drone deployment,” explained Triad President/CEO Walter Lappert. “There were underserved areas and underutilized technology that had a lot of potential.”

To found the company, Lappert drew on previous AV experience in the private sector and as an armaments systems specialist for the Air Force in places like Afghanistan. “I’ve always been into remote AVs, and have been building my whole life. The military taught me to work on multi-million-dollar systems and not screw up.”

Lappert’s 2,500-square-foot shop produces a mix of customized and original vehicles. As a small-business operator, he has to make smart choices. “We outsource a lot of what we do. Can we do it? Should we do it? Does it make sense to do it? It makes it a lot easier to give the customer what they need.”

Quickly, another part of Lappert’s background supported a concentration on waterborne vehicles. He customized two off-the-shelf boats, and designed Catamaran and larger Trimaran surveyors to be unmanned and fully customizable. The Catamaran’s data-collection capabilities would figure in the Lapalco rehab.

“It was the culmination of all my skill sets, and I saw water as easier,” the soft-spoken Lappert continued. “There are a lot less variables with the same tech. And I grew up in Hawaii. I’m used to the ocean and the water. Florida was calling.”

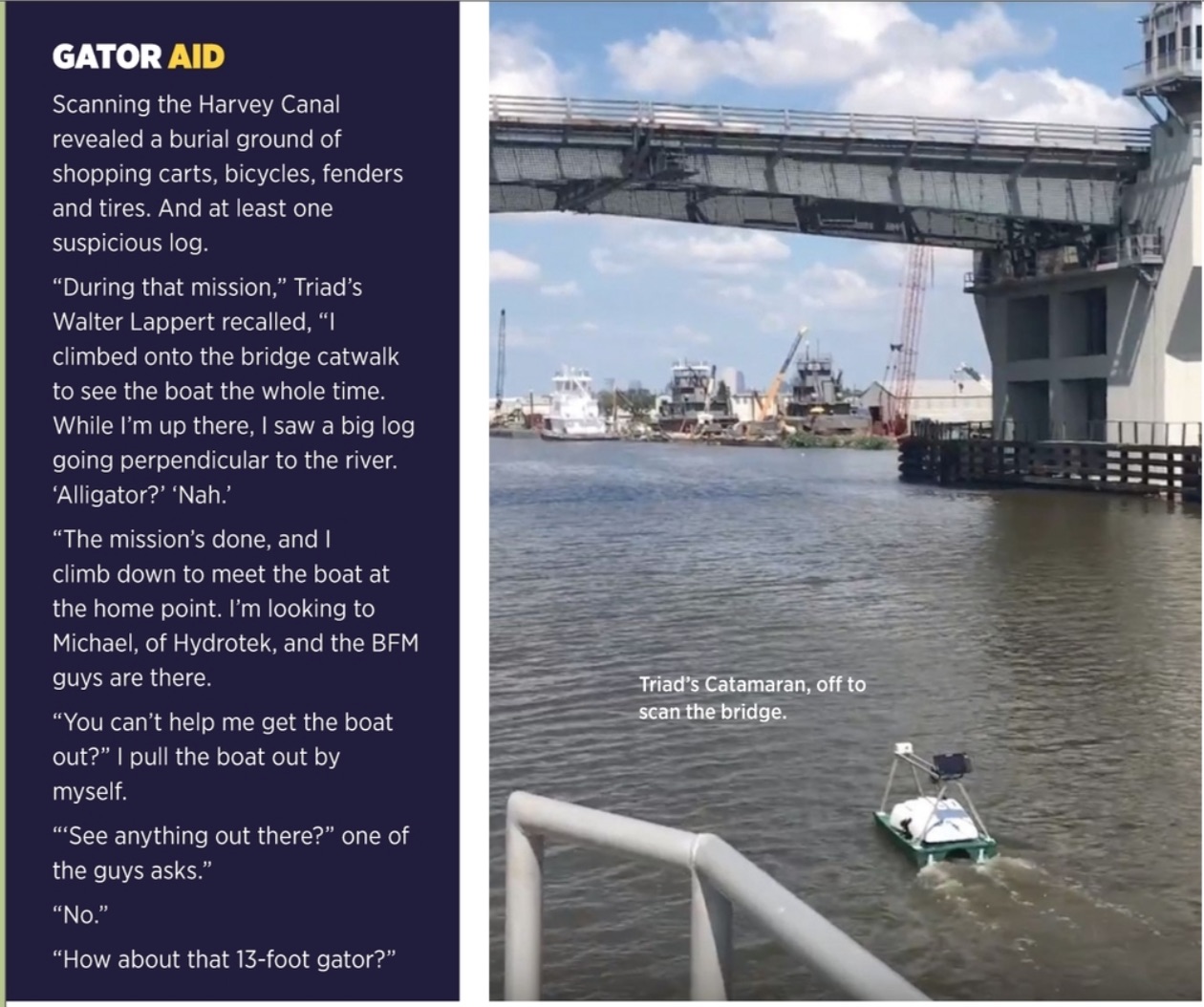

Early in 2019, Triad and BFM hooked up via a mutual affiliate, Higgs Hydrographic Tek, which also is based in Tampa, and which would collaborate on subsequent work. A manned hydrographic project at a pond-dotted country club proved to be successful, and BFM purchased a customized SL-20 boat, with Hydrotek ensuring accurate hydrology. “It’s been great,” Poche said.

An autonomous collaboration followed at The Pump House, in Des Allemands, Louisiana, involving new construction and expanding a levee. “They had a 50-pound torpedo decoy thing,” Lappert recalled about BFM’s magnetometer, “and we did the magnetometer survey to help locate an underwater gas line.” The water was muddied, as three-foot-diameter tubes pumped thousands of gallons of water, changing the swamp floor.

Over a day of work, Triad also deployed a single-beam, dual-frequency sensor “to measure the sediment layer at the intake of the pump house.”

There was another reason to survey autonomously—one that would literally rear its head again: “This is gator-infested; these guys don’t want to get in there.”

LAPALCO FROM ALL ANGLES

August brought another collaboration, this one around the existing Lapalco Bridge. To paraphrase the 1960s band The Yardbirds, it would expand to go “over, under, sideways, down.”

LAND: “We hired Triad to do the LiDAR on land,” BFM’s Chad Poche recalled. “That helped us because it set up our field work. He [Lappert] LiDARed the whole bridge in two days. It would have taken us multiple weeks.”

Poche voiced another reason for AV deployment. “It also was definitely safety,” he explained. “He could drive it on the bridge and we didn’t have to close out lanes or put guys in the middle of the bridge.”

Approaches and road bed were surveyed using a manned SUV with a rooftop scanner. Driving at night encountered less traffic and improved data collection. So did Triad’s renting of a Phoenix LiDAR, the Ranger, which is based on the RIEGL VUX-1 and augments IMU and GPS capabilities. “It’s overkill,” Lappert recounted. “But we could do it quickly and it’s also a very universal LiDAR.

“The car part of the laser mission alone would have taken two crews 40 days,” Lappert said.

AIR: The very next morning, the Triad team swung right into aerial data collection, with a 30-minute run. “We wanted to get a known, exact height of the bridge, cranes or other obstacles,” Lappert noted. “We used a Phantom 4 Pro. By measuring the highest object, we then could allow a 50-foot buffer on this mission.”

That first flight was manned, but for the next flight the Phantom 4 was reprogrammed for autonomous photogrammetry. “Making sure we’re covering the entire site” was the idea, Lappert said. This subsequent sequence—down and back, on each side—used a stock photogrammetry camera to collect the color imagery that would enable an ortho map.

A LiDAR run followed. Now flying an M600 on a slightly different path, LiDAR collection took about two hours from setting up the RTK base station, then planning, flying and dismantling. Safety was again paramount: runs were coordinated parallel to the roadway to protect the people below; observers were spread out to maintain line of sight.

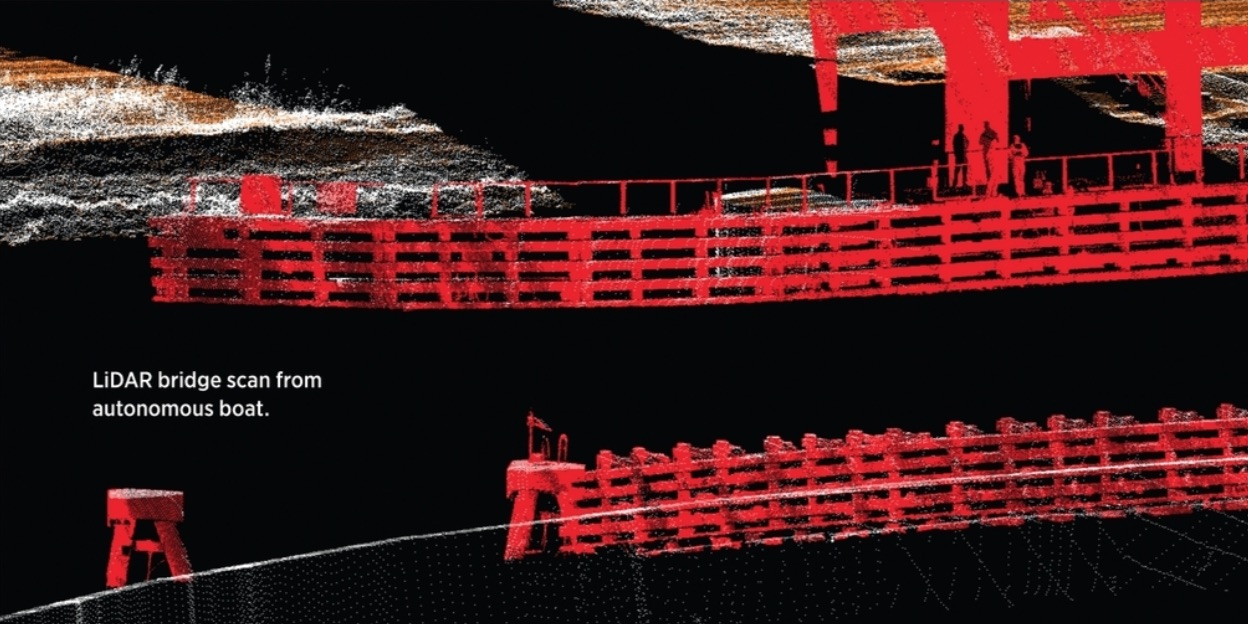

WATER: Right after the aerial runs, Day Two saw the Catamaran’s voyage under the bridge. The LiDAR came off the UAV and was flipped upside down onto Triad’s custom Catamaran, a green five-by-four-by-three foot vessel with a white housing for sensors that stream live data back to a remote operator. The LiDAR was mounted upside down at a 45-degree angle for maximum data-collection efficiency. “The way the laser is emitted,” Lappert explained, “it wouldn’t be able to see the same obstacles if perpendicular.” Also, the Catamaran is designed to be universal and adaptable, with magnetometers, single sidescans, lasers—”different arrays for a mission,” Lappert said.

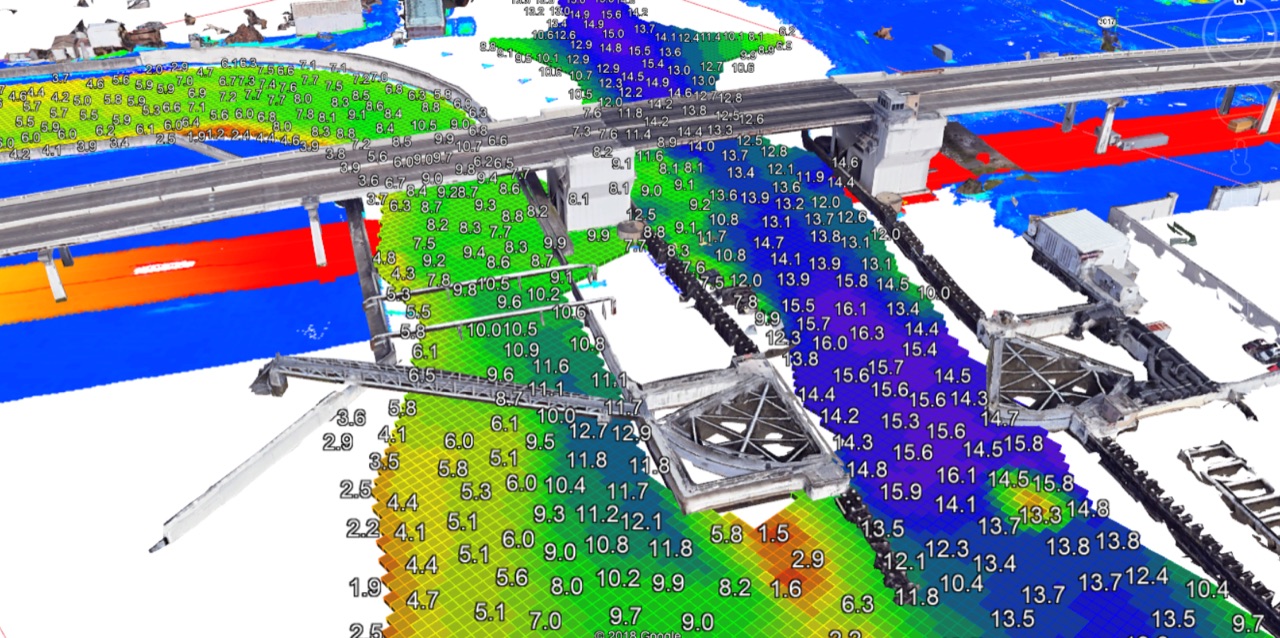

An A-frame mounting system on the Catamaran provides front and rear anchors for GPS and LiDAR. LiDAR data was gathered by driving around the closest edges and center edges of the bridge structure. Sonar data was amassed to calculate the area to be dredged.

Poche: “He got some areas that we couldn’t get to with our equipment. We could have used our 22-foot boat, but some of the locations were isolated, behind fenders, remote. Since he was out there, we had him do it.”

Three days later, Triad delivered a 360-degree point cloud to BFM that combined aspects of the captured land, air and water LidDAR data.

RETURN ENGAGEMENT

Another day in the water came a month later. “We ran that same dual frequency, single beam sonar to calculate the volumetrics of the sediment layer,” Lambert recalled. Then the route was replicated, running a Humminbird™ Fish Finder “patched with some custom software that knows how to reinterpret and make a map out of it.”

Post-hydrology analysis replicated the previous process: XYZ coordinates, extrapolating contour lines in CAD for volumetric data. The sidescan, Lappert explained, allowed for “a giant ortho image for review.”

One finding yielded an unpleasant but important surprise for a channel frequented by ships with fairly deep drafts. “There was a spot they thought was 25 feet deep; it turned out to be 13.”

FORWARD MOTION

“Customization,” said Kamyar Shah, who joined Triad as COO in June, “requires more effective and efficient solutions, cutting edge at reasonable cost.”

To both hone and expand its niche, Triad now offers about 10 customized or unique products. Coming full military circle, Lappert has sold a Catamaran and the larger Trimaran to the Navy. Lappert designed the plans in CAD, collaborated with a manufacturer in Hawaii for the hulls and then did the wiring. “Next version, I’ll 3D print the whole boat.”

Lappert just sold an optionally piloted, 12-foot survey boat with bigger sonar to another customer. “Projects with extremely high safety criteria need a second, rescue boat. Now, with one boat, “they can manually drive, then be autonomous from shore in safety zones, meshing data sets without a break. He’s also returning to his aerial roots, building “a giant, long-endurance hexacopter. The goal is an American-made platform, 40 percent larger and with better flight characteristics than an M600.” To that end, he’s using a Pixhawk2 Blue Cube autopilot, which also is made in the U.S.

Over at BFM, the company has been able to extract data from the point cloud to comply with an LADOT notification that it would accept particulars only from “hard surfaces” such as the bridge’s concrete and its asphalt roadways. And Poche, the EVP, remains a satisfied collaborator. “It’s a high-profile job, a feather-in-our-cap job,” he said about the overall bridge experience. And Triad’s role? “We’re very satisfied with their work, and the project is going very, very well. The final delivery will be awesome.

“We enjoyed their work so much that we’re buying a drone from them,” Poche continued. This time, it’s a Sentinel, an aerial drone customized with high-accuracy PPK photogrammetry and a VMAP PPK receiver to augment the company’s already-existing LiDAR capabilities.

“The value is not just in the drone,” Lappert noted about Triad’s capabilities. BFM “sent four guys out here [Tampa] for training on the platform and to learn how to process the PPK telemetry.”

Triad’s also subcontracting PASCS—Precision Aerial Compliance Solutions—to BFM, “to collect massive terrestrial data on a car.” Lappert noted an irony of the information age: “Before, the bottleneck was the field crews; now it’s the data processors.”

Being a one-stop shop, Lappert concluded, is key to running a small AV company. “It’s about being that Jack of All Trades, a technical expert, understanding process and end goals. And saving time, money, lives.”