On-the-fly solutions by Duke Energy and Southern Company helped repair storm-damaged transmission lines, spurring innovation and expansion at two major power companies.

Jacob Velky, Duke Energy’s manager unmanned aerial systems, was in his Charlotte, North Carolina, office, but part of his focus was concentrated across the state. In Wilmington, a truck that was essentially “a mobile tool box, including a line-stringing drone,” stood ready should Hurricane Dorian reprise the damage it had just visited on the Bahamas. If so, lessons learned during 2017’s Hurricane Maria could again come into play.

When Maria roared across Puerto Rico in September 2017, its 175-mile-an-hour winds triggered more than 3,000 deaths and $90 billion-plus in damages, including numerous downed power poles and lines. Eventually, drones flown by, among others, Duke Energy and Southern Company, would play innovative roles in power restoration.

UAS ROOTS

Duke Energy’s emerging technologies group began conceiving UAS use late in 2014. Over time, Section 333 and Part 107 authorizations were secured, and UAVs began inspecting solar panels, turbines and power lines. Maria would stretch that bandwidth toward data collection and power restoration.

Beginning in January 2018, Duke Energy answered Puerto Rico’s mutual assistance request by putting 220 workers into a ravaged, mountainous environment. “Vegetation made it difficult to even assess where the lines were or where they were supposed to be,” recalled Velky, whose leadership role had been formalized the year before. “Outside of line stringing, we were using the drones to recon, mark locations, survey how linemen could access those locations.”

UAS were not a panacea. “The 55-pound limit and battery life made drones difficult to use over time in the field,” Velky noted. “Helicopters could do 10-12 runs; drones, one or two. Small drones could be repowered from car chargers, but larger ones were more difficult to energize once teams left their hotels.”

Yet UAS usefulness soon manifested itself. Towers and poles could be up to 1,200 feet apart, and wire had to be run next to and through both sides of structures. It was linemen themselves who signaled that drones could be useful, and safe, in these tight situations.

“The idea to use a drone to pull a light line came after a [fatal] helicopter accident in northern Indiana,” Velky explained. The in-place helicopter protocol involved “pulling steel cable up to the structure, clipping a long ‘needle’ onto the center phase, detaching it, flying to the other side, reattaching it and pulling the needle and corresponding wire through the center of the tower. “Stringing transmission lines was amazing,” he continued, “but absolutely a dangerous job.”

Velky’s thought: “Use the helicopter on the outside phase, but could a drone fly through the center phase with a light line without having to use this needle?”

Velky, who holds degrees in aeronautical science from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and business administration from Wake Forest University/Charlotte Center, brainstormed with two UAS colleagues. “We weren’t even a formal team.” Over a weekend, the idea that emerged involved stringing lightweight nylon parachute cord as a guideline to attach permanent steel cable. UAS Sensor Specialist Isaac Medford suggested that an electromagnet could be remotely triggered. Sourcing parts from the internet, he created his own element to tie to the drone, attach a metal clip to the cord and magnet, flip the [magnet-controlling] switch and drop it accurately on the other side. He used his private 3D printer to build a housing for the components.

“The system provided a safety mechanism too,” Velky added. “We could separate from a line if it hung up and still recover the drone.”

The concept was tested in Indiana, and then in a swampy area of North Carolina. Once in Puerto Rico, an AceCor Technologies’ ZOE quadcopter drone was used to connect poles on two different mountaintops. The ZOE can be folded from both its front and back, lift payloads of up to 6.5 kilograms and sustain winds of up to 35 knots per hour. Maximum flight time is put at 40 minutes.

The team did 10 pulls over a week, stringing 9,000 feet of cord via drone. It also provided proof of concept. “It made our jobs easier, more efficient and a lot safer because now we don’t have to put humans in the ravines and gorges to try to find the old wire,” Rufus Jackson, then VP distribution, construction, maintenance, told the company’s in-house magazine. “Basically, we have the new pre-line hung up, and now we have something to connect and to finish the restoration.”

For Velky, the first wire pull was especially poignant. “We flew in a backyard of a house on a hill, and a mother and son came out to watch us. Pulling our line that was going to this specific house absolutely made it special.”

SOUTHERN “STEROIDS”

“Southern Company did it on steroids.”

Velky was referring that energy giant’s subsequent work in Puerto Rico, where the Atlanta-based company’s 30 pulls strung more than 13 miles of wire during an approximately two-month deployment.

Southern Company’s UAS implementation also was conceived in 2014, and flying debuted the next year. As at Duke Energy, that was after a fatal helicopter accident, in which a Southern Company employee and a contract helicopter pilot died. The company’s first UAV, an Aeryon SkyRanger, was able to conform when Southern became the only utility with a section 333 authorization granted when it applied. Utilization from examining electrical transmission to early fault detection followed.

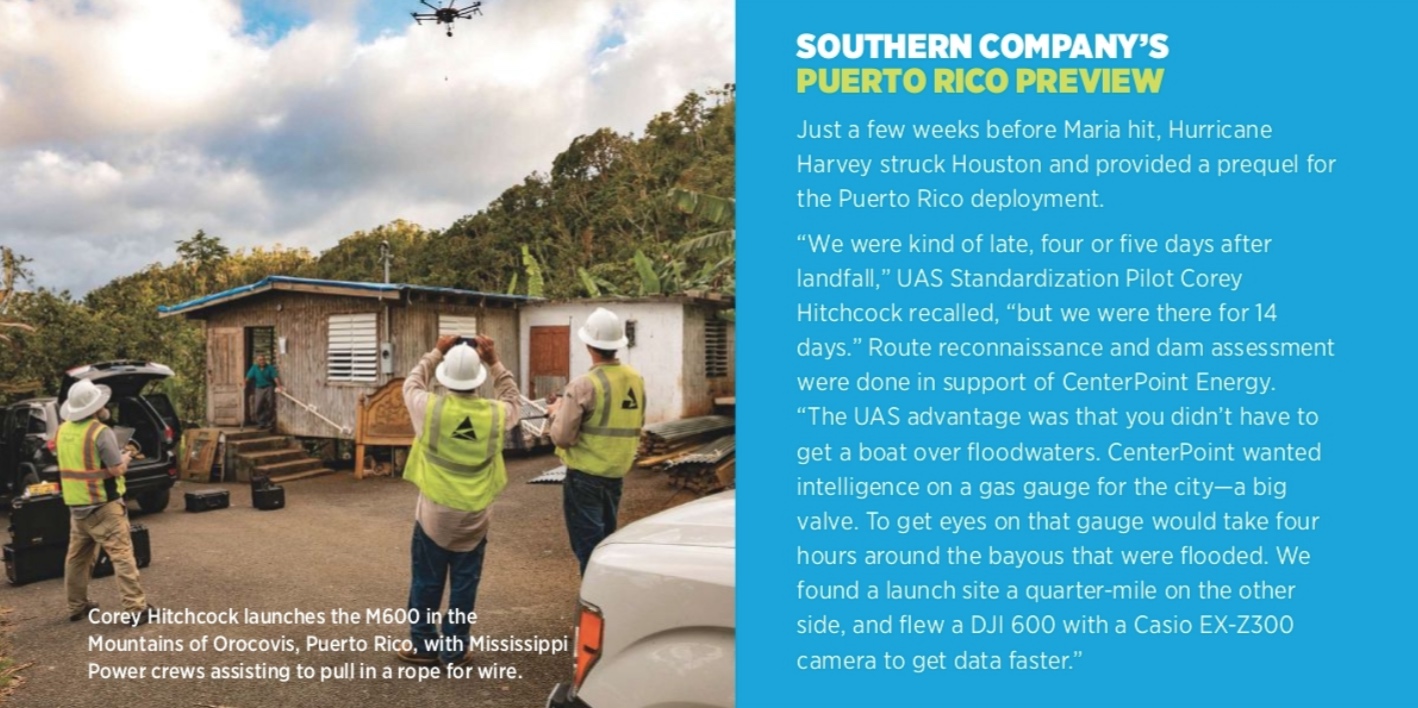

In 2016, Corey Hitchcock became a UAS standardization pilot after 16 years with Southern subsidiary Georgia Power and participation in the overall UAS effort. A 2011 airborne accident during a stint in the Georgia National Guard had ended Hitchcock’s career as a lineman, ironically spurring an interest in UAS and leading him to work toward a BS in unmanned aircraft systems applications from Embry-Riddle. He’s now the main trainer for UAS. At the end of 2017, when Southern Company’s UAS effort was fully defined, Dean Barefield became the UAS program manager, following an army career that included flying Boeing AH-64D Apache helicopters.

Once the assistance request brought Southern Company to Puerto Rico, a sophisticated technique for stringing lines was shelved. “We quickly realized the challenges of pulling rope in a jungle environment,” Barefield recalled from a company hangar. Southern Company’s innovation involved a modified DJI Matrice 600 stretching out a lightweight test line, then a bull line, alternately pulling a conductor. Unlike Duke Energy’s electromagnets, this method used radio-controlled, servo-actuated releases. “The launch team would communicate by radio, and the pilot directly communicated with the receiving team,” Barefield continued.

Hitchcock shared fond technical memories. “Once, we dropped water off to our people on top of a mountain. We also put wire in a guy’s hand on a pole. The pole was on the top of a little hill. A bucket truck was blocked by a landslide. The lineman climbed out of the 65-foot-bucket stretched out all the way, climbed another 20 feet. He kinda stood by there to receive the rope, tied off the base, pulled in a bigger rope and then the wire.”

Drone deployment in Puerto Rico yielded significant cost savings for Southern Company and took months off time to completion, Barefield estimated. Now, more than 100 Southern Company pilots are flying 127 aircraft, mainly DJI products, with “a couple of senseFly eBees being used for mapping by the GIS department.”

LESSONS LEARNED

Expanded UAS use: A series of vertical and linear applications reduce employee risk during missions from solar inspection to assessments within confined, GPS-denied environments such as cooling towers. Cameras with 30x optical zoom and thermal readings are augmenting data acquisition.

Cross-company expertise: “We’re already seeing the first step,” Velky said about Duke Energy’s UAS growth. Velky’s six-person drone team now has three UAS pilots and a sensor specialist. Bryan Williams, who’d worked alongside Velky in Puerto Rico, is UAS coordinator of internal development. Overall, Duke Energy now fields 70 drones: “smaller, shoebox China drones, larger quadcopters from Canada’s Aeryon and octocopters from Netherlands’ AceCor,” Velky said.

“We had zero linemen in a transmission organization using drones in Puerto Rico. We’ve trained 90 linemen, not to pull lines, but to operate a very small inspection drone.” Velky called it “crawl, walk, run.”

Duke Energy’s action plan, Velky said, asks linemen to “use these drones before they drive, to see if there are hidden hazards—holes, creeks—covered by vegetation.” Another 30 linemen are slated to be trained by year’s end. Velky: “You start seeing a subset becoming power users, helping to preach how this is useful. A snowball grows on itself.”

Integration: It’s important to integrate UAS with other corporate aerial resources. Duke Energy helicopters patrol more than 32,000 miles of line; Southern Company operates seven regulated utilities with about 200,000 electrical transmission and distribution lines and tens of thousands of miles of natural gas pipelines to inspect.

Duke Energy’s dedicated drone team and the company’s working helicopter personnel are now integrated. “It’s a strategic move,” Velky noted. “When I joined the aviation services organization, the helo pilots didn’t know how to approach me. I can tell them that we can complement and learn from each other, and build Duke Energy. We had to have that conversation.

When the FAA allows me to do BVLOS, I’ll understand the camera and the data because I’ve worked with the manned assets. Don’t dismiss your aviation department: it can be a key resource in helping you leverage and deploy drones in your organization per a base level of knowing how to operate in the national airspace.”

At Southern Company, a “self-dispatch” team approach now supports UAS fleet management. Barefield: “Our ability to self-dispatch speaks to having trained internal pilots, transmission engineers and distribution employees who are certified and are out where they are needed for damage assessment and restoration.”

Storm Deployment: Trained pilots, while necessary, are not sufficient. “Before there’s a storm”, Southern Company’s Hitchcock noted, “you need to be planning your response, getting the emergency managers to know and trust you. Plan exercises with different public safety entities so everyone can get warm and fuzzy, and know that we’re on the same page.”

When Hurricane Dorian reached North Carolina, Duke Energy fielded 15 contract drones and two internal teams with large electromagnets, spools—what Velky called “all the pieces of the equation.” Fortunately, “damage in North Carolina was not as much as anticipated, but the deployment—one day of assisting with damage assessment—was a valuable exercise in preparation.” Southern Company also has maintained its hurricane presence.

Flying a Safe Future: Southern Company has partnered with Skyward, a Verizon company, to enhance its fleet management. “Pilot information, historical data and mission overview are captured at a high level across the system,” Barefield noted. “This leads to operational expertise and performance-based excellence.” The resulting standards, Hitchcock added, “position ourselves for what we believe will be the features of the regulatory environment”—including eventual BVLOS flights.

As we concluded our conversation, Hitchcock mused about a, well, empowered future for UAS. “It’s gotta be adaptable, adoptable, scalable, and we can replace manned fixed wing and rotorcraft for inspections once the regulatory environment becomes more favorable.” And it can be safe. “One life is too many.”