uAvionix Miniaturization Opens the Airspace for UAS

Integration of unmanned systems into the National Airspace System is a long journey. Leading the way, uAvionix has progressed from hobby-grade equipment to certified avionics in general aviation, then for unmanned systems, and finally for defense products. The company has moved the UAV industry forward, placing FAA-certified products on the market and enabling the regulatory environment within which the rules for manned and unmanned air systems’ interactions will be made.

Along its way, uAvionix has enabled both general aviation (GA) and UAS to participate in the benefits of Automatic Dependent Surveillance– Broadcast (ADS-B) without the high costs of installation. ADS-B is a surveillance technology in which an aircraft determines its position via satellite navigation or other sensors and periodically broadcasts it, enabling it to be tracked by other craft. uAvionix’s many products from pingRx to tailBeaconX integrate GPS with communications links to ensure all aircraft in the sky know their own position and those of others around them.

The company has also pioneered command-and-control (C2) technologies for extended UAV flights beyond visual line of sight, recently conducting a 40-mile demonstration f light.

“In the very beginning, our founders were deep-seated in the remote control [RC] industry,” recalled uAvionix President Christian Ramsey. “[CEO] Paul Beard invented Spectrum RC, which took the RC industry from being able to use only a couple of frequencies, so only a couple of aircraft could be flown at one time, or they’d interfere and crash. He invented a frequency-hopping technology that revolu- tionized the whole RC industry.

“Prior to that, he was CTO of Cyber Silicon, a chipset manufacturer. As a designer in the ASIC world, he had knowledge of component miniaturization. He was also a helicopter pilot. He noticed a convergence happening. In 2014, when the new mandates required him to purchase ADS-B for his helicopter, he saw the evolvement of hobby drones into more intelligent craft. ‘If I can miniaturize ADS-B technology,’ he said to himself, ‘it’s going to be important in keeping drones from hitting my helicopter.’”

“We realized quickly that if you’re going to be sharing airspace with manned aircraft,” uAvionix COO Ryan Braun said, “you have to achieve some level of integrity. There are certain quality metrics, design assurances about the data output from your GNSS equipment, that’s part of the regulatory environment.

“Safety assurance in anything that moves, and especially anything that flies, that’s what we’re concerned about and focused on,” he added.

A FIRST BIG STEP

The company’s initial funding was for min- iaturizing the technology inside a 5-pound box in a GA aircraft into something small enough for drones. With backing and an influential first customer—Google—uAvionix quickly achieved that goal for what became Google Wing. It then began to build other products based on that technology.

To miniaturize ADS-B transponders, uAvionix engineers designed and purpose-built their own GPS chipset, a significant achievement within the GPS industry but virtually unheard of outside it.

“We had gone to all the GNSS manu- facturers and told them what we wanted,” Braun recalled. “They said ‘It can’t be done. Our smallest box is bigger than your beacon that it’s supposed to go inside.’

“That was the impetus for us to do it: Size, weight, power and cost [SWaP-c], your typical motivation in a lot of electronic miniaturization.”

uAvionix spun off an entire effort to build and certify a GPS to go into its products—and succeeded wildly. It is now the No. 1 or No. 2 GA product supplier in the U.S., something that occurred in the last 18 months, and it is No. 1 in the UAV market.

“Trying to shrink down some of these high-integrity GNSSs was essentially a nonstarter,” Braun continued. “We specialize in miniaturizing a lot of these RF technologies to put into unmanned systems. We brought in front-end technologies from the commercial sector and integrated that with our hardware and software algorithms, all done internally here, to obtain receiver-autonomous integrity monitoring (RAIM) and satellite-based augmentation systems.

“Put it all into a single package, the size of a silver dollar: the GPS receiver, patch antenna, the power, lightning protection, everything you’d want to put in an aircraft GPS that weighs grams, not pounds.”

The uAvionix receiver is capable of calculating GPS plus another solution simultaneously; it can support four different constellations plus SBAS. What has become known as the “truFYX” GPS has been TSO-C145e certified in skyBeacon, tailBeacon, tailBeaconX, and for the first time ever, as a standalone GPS receiver.

NEXT!

“We went from those chipsets and OEM modules for Google to developing stand-alone products,” Ramsey said. “We kept moving up the ladder over the years from receivers like pingRx to transceivers, and then farther upward in terms of transponder technologies, increasing the complexity of the solutions.”

Transmitting on ICAO-regulated aviation frequencies requires FAA approval. With agency guidance, uAvionix learned the certification process and produced equipment on the required tolerances. The FAA acknowledgment of its expertise, an important milestone for drones, occurred in 2016.

At the same time, the FAA was coming to grips with rulemaking necessary for UAV integration into the National Airspace System (NAS). The agency became very interested in what uAvionix was doing in its Bigfork, Montana facility. “We worked closely with their Policy and Innovation Group,” Braun said. “They develop issue papers or policy, saying here’s how you prove a system meets a certain safety assessment. Some things are very clear, and some things are very fuzzy: you must prove you meet the safety cases.

“For example, how do you prove, how do you integrate new, modern technologies into avionics? We spent a long time focus- ing with them on how they wanted that done and integrating that with all that’s been developed in the commercial sphere over the last 10 to 20 years.”

“You have to prove that the function you’re offloading is going to operate in all conceivable circumstances,” Braun said. “Proving it through enablement and disenablement of certain functions. Taking the system, poking it with certain inputs and seeing the outputs.”

Common to all uAvionix products is the idea of placing the devices somewhere on the aircraft that already has power and also has the perfect position for an antenna. The equipment can be installed in less than an hour, and at relatively low cost to the owner or pilot.

“We have had a number of simultaneous projects that have been released in a short, very active period recently,” Ramsey said, “using synergies between various products to bring them to market in a short time-frame.” ADS-B has been put it into 10 dif- ferent form factors by uAvionix, from the very traditional to the very unique.

DEFENSE

“Simultaneously we came across the opportunity to develop Mode 5 Identification Friend-or-Foe [IFF] technology for defense markets,” Ramsey said, “using the same architecture, but with added complexity. So, now we do technical standard orders [TSO] certifications for UAS and GA and AIMS for the defense market. We look at everything from a multi-market perspective.

“We’ve been very successful in each of those, although the market is still a bit early for some of those products. Airbus Zephyr, the world’s leading solar-electric UAS, is a good customer for ping200x. All those guys need a certified GPS or certified transponder, or both. There’s a lot of opportunity for us out there; it’s still an early market.”

“The algorithms themselves were all developed internally,” Braun said, “completely from scratch. They came out of a study of what the requirements bound us to, and what we could bring in from the industry.

“It was a thrilling thing to watch it come to life. We continued to build up accuracy, making it better and better. From development kits to building up our own systems and passing the battery of tests—that’s kind of an engineer’s dream, building something from scratch.”

THE FUTURE

uAvionix sees a strong need for ground C2-based infrastructure that those airborne radios communicate with. This, too, has a very high bar of safety to meet. The company has produced a software and services package called Skyline, an infrastructure managing the health of the network, the handoffs, gauging capacity and taking care of failures. The investment in managed infrastructure service is increasingly necessary for pipelines and railroads, the early customers.

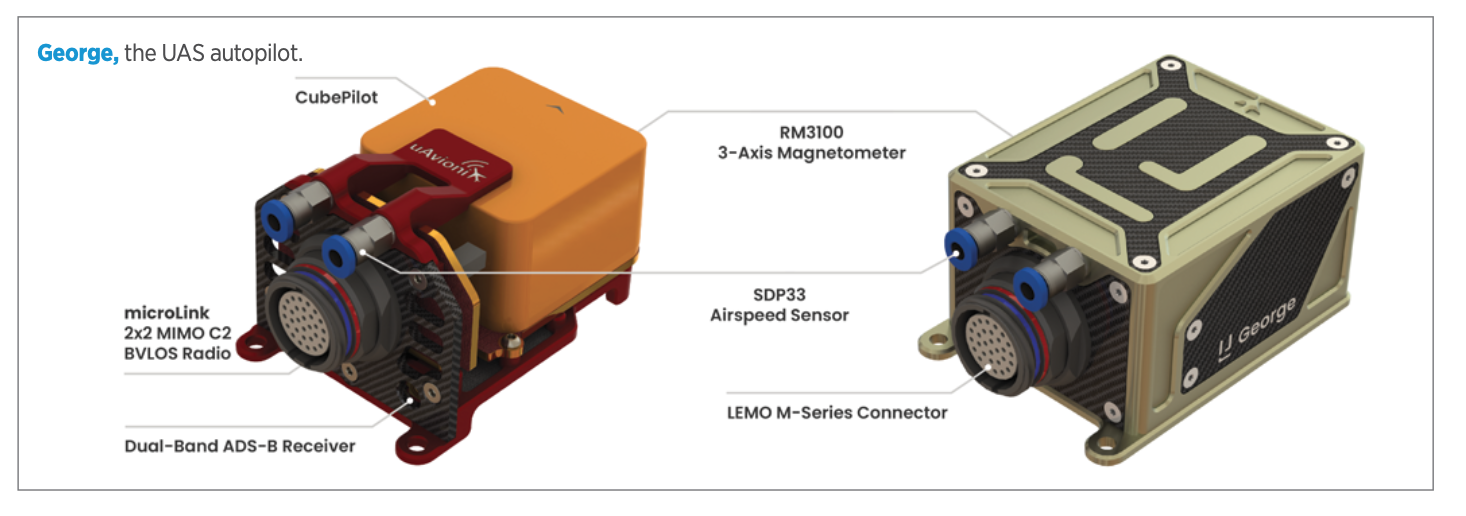

Another important market is autopilots. How will autopilots be certified in the future for unmanned systems? uAvionix has a candidate for that: George, now test-flown and entered onto the market. George combines a decade’s worth of innovation from the open-source community with uAvionix’ knowledge of certification capabilities.

“There isn’t a TSO out there for drone autopilots—yet,” Ramsey said.

“We’ll wrap that in a layer that includes design assurance; DO254 level C is what we’re targeting, with high levels of RF and EMI testing.”

Overall, the company is moving beyond core radio technology into ecosystems, raising the bar for quality and integrity of GPS in all unmanned systems. This enables more applications with different requirements in diverging market sub-sectors.

For the future, Ramsey sees detect-and-avoid capabilities becoming a critical enabler for UAVs and envisions a company venture into that space. “The individual sensors that address that, all the components still have challenges, each one of them. You’ll need a layered approach of different technologies with complementary capabilities, that plug each other’s holes.

“If you go back to the very first FAA roadmap,” he concluded, “it identified detect-and-avoid as the big technology to develop. It’s still the primary key technology that needs to be developed to unlock the airspace for unmanned air systems.

“We’re well suited to get there. We learned from our foray into the GA space that we can move faster than the industry. We’ll develop the technologies to meet those needs.”