Image credit: SEA-KIT International

The North Sea is famous for weather that no sailor should be out in—and soon, some won’t have to be. That’s because work is beginning on a new uncrewed 18-meter ship geodata specialist Fugro has commissioned for North Sea operations from SEA-KIT International, a shipbuilder based in Tollesbury on the United Kingdom’s Essex coast.

The new model will be 50 percent longer than SEA-KIT’s current 12-meter boat, but with three times the tonnage, according to CEO Ben Simpson. It will be able to carry up to 7 tons, and sail in Force Nine seas. The 18-meter vessel will also sail with much more power in its hold, jumping from 36 to 200 kilowatts and commensurately higher voltages.

Simpson, a naval architect and former captain/engineer, began working on uncrewed vessels in 2018. That’s when a team of alumni of the GEBCO (General Bathymetric Charts of the Ocean)-Nippon Foundation ocean mapping training program at the University of New Hampshire approached Simpson “to design their solution for mapping over the horizon.” This, he continued, would involve “unmanned ocean mapping down to about 6,000 meters over a period of about 72 hours, including collecting and processing the data, via satellite, using data collected both on the surface and from an autonomous underwater vehicle.”

After that solution took home the $4 million grand prize for the Shell Ocean Discovery XPrize of 2019, Simpson and some members of the GEBCO team decided to apply that technology toward building uncrewed vessels, and he founded SEA-KIT International.

Rapid Acceptance

The seaworthiness of SEA-KIT’s 12-meter boat has been accepted by insurers relatively quickly, according to Simpson. Backup requirements for coverage dropped rapidly as tests continued.

“We started off with a guard vessel within a few hundred meters, and then within 6 months, they went to 200 meters, then 800 meters, then to the point where we got insurance without having a standby vessel,” he said – even for a recent 22-day mission surveying 1000-plus square kilometer of previously-unmapped ocean floor.

One factor that has quickened that transition is that SEA-KIT engineered the ship to be controllable entirely by satellite. “We set out always to be over the horizon, in a way. All of our data was going to come by satellites, which made us very much unrestricted,” Simpson explained.

“There are a lot of companies out there that are still using line of sight technology or standard terrestrials in 4G, 5G, and that does restrict them quite a lot when you go over the horizon. A lot of them need to have another vessel to be able to get that data to them,” he said. SEA-KIT, on the other hand, designed its ships to communicate with three different satellite systems, ensuring seamless coverage anywhere.

Remote But Virtual

SEA-KIT ships, however, are not yet piloted by artificial intelligence. Simpson predicts they will achieve full autonomy in five to eight years; for now, the vessels are operated remotely by experienced human mariners qualified to captain crewed 12-meter vessels.

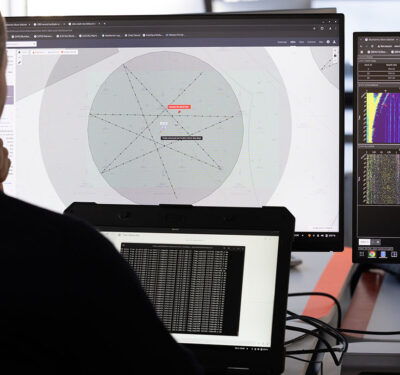

The remote captains’ virtual bridge gives them the same information as a captain on an actual bridge might have, including TV cameras, radar imagery and even sound.

Currently, SEA-KIT is piloting a ship on an oceanographic mission in Australia all the way from the UK, as well as a remotely operated underwater vehicle. In Australia, “we are deploying a 350-kilogram ROV down to 300 meters, and that’s all controlled through the vessel up to the satellites and back down. So, you’ve actually got people flying things under the water, not just scanning, but actually manipulating—doing jobs—and you can control that from anywhere in the world,” he said.

Not only is the commute of a SEA-KIT captain easier, so are the hours: the night watch skipper can steer from a daylit part of the world. “You can certainly organize work patterns to not include a night watch. You can hand that watch of that vessel over to the next time zone, so the dark watch doesn’t really need to be a dark watch anymore,” Simpson said.

Bigger and Better

Work on the hull of the 18-meter model will start in March, with delivery scheduled for early 2023.

But even as the company begins to build its larger ship, Simpson has set his sights on an even bigger challenge: “We have a 22-meter already on the design books and ready to go,” he said.

While the current vessel is a hybrid that can run on either diesel or diesel-charged batteries, Simpson is also beginning to experiment with the use of a hydrogen fuel cell to power the boat for missions that need to run quietly.

Applications on the drawing board include vessels that could serve as a platform to launch and recover remote vehicles such as large AUV/UUVs or ROVs for use in deep-water bathymetry, offshore and subsea asset inspection and hydrographic surveys; naval defense and maritime security operations; and support vessels for giant yachts. An uncrewed support yacht could provide safer and more economical logistical support or, company literature says, carry “a range of tenders and toys.”