Best known for its drone deliveries, Wing started under Google X in 2012. It was housed within Alphabet’s Moonshot Factory, where the mission is to advance “radical new technologies to help solve the world’s hardest problems.” Driverless car Waymo and Verily, a global health care data accessibility initiative, emerged from the incubator, and so did Wing. In 2018 Wing became a full Alphabet subsidiary with the transformative goal of redefining transportation, reducing road congestion and expanding economic opportunity.

Moonshot businesses have to show commercial potential to be emancipated, and Wing has now conducted more than 100,000 flights over three continents. But in 2019, the FAA noted a key issue, remarking that the existing air traffic control systems “cannot cost-effectively scale to deliver services for UAS. Further, the nature of most of these operations does not require direct interaction with the ATM [the FAA’s Air Traffic Management system].”

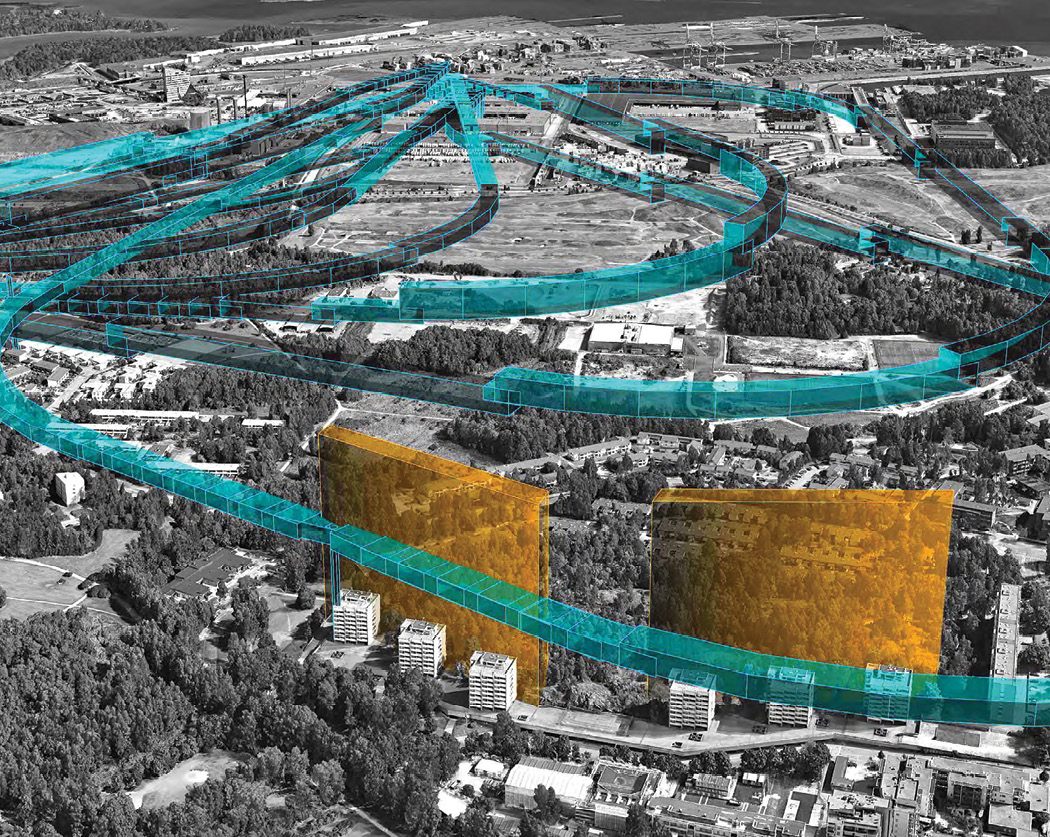

One Wing solution is OpenSky UTM (Unmanned Air System Traffic Management) technology, which engages in real time route planning and management of its drone deliveries. The tool is part of Wing’s mission to foster an ecosystem of approved and shared safety communication standards between multiple operator types and airspace authorities. Safety at scale, deconfliction/“no-fly” notification are system precepts.

Wing has worked with the FAA, NASA and international organizations to create standards and technology for interoperability and remote ID. The FAA has put forth a UTM Concept of Operations 2.0, and the EU is building out a U-Space autonomous drone integration counterpart, and Wing is collaborating with both agencies. Wing also has brought together UAS Services Suppliers (USS) to support interoperability throughout the flight cycle. Wing staffers were active within ASTM International (formerly the American Society for Testing and Materials) to develop the group’s consensus Standard Specification for Remote ID and Tracking that was put forward in January.

To learn more about Wing’s UTM efforts, Inside Unmanned Systems spoke with Reinaldo Negron, a Wing/Google veteran who, as head of UTM at Wing, is charged with addressing how air traffic management can evolve beyond individual flight controllers and, as the division puts it, “solve for equity.”

Negron’s thoughts follow, edited for space and to add definitions.

The Vision

We believe in empowering everyone to safely access the sky. For us, that falls into several ways. “Empowering” means making it easier and simpler for operators to fly and know how to be compliant, and to enable more people to take their drone operation and do what they want to do.

That goes beyond Wing. How do we collaborate with other industry partners also looking to serve operators? How do we have a collaborative and open sky that enables us to work together for the benefit of all operators? And how can we do that in a way that enables this industry to continue to grow for the very diverse set of operators that exist there?

For us, we’ve been building the technologies, policies and frameworks to enable that open airspace system to happen. We recognize that we have to move to a digital world where people are not looking at every drone, as is in air traffic today. And we recognize the diversity, again, of not just the drone but the types of operations beyond the ATC [air traffic control] we see in traffic today.

The Rationale

For us, investing in UTM is really critical because the alternative’s not great. If you look at the existing aviation system that manages tens of thousands of flights and billions of dollars, not only is there a cost, but the innovation cycles, the rate, the length it takes to get something new out there, that can be decades-long plans in an industry that changes annually. From that perspective, we can’t live in a world with that pace of innovation.

It’s really prescriptive. Most planes fly pretty similar. Drones are not the same way at all. It’s going to be a new type of battery, obstacle sensor, a new way to do point cloud-based navigation, and that will push us to a very, very different paradigm very frequently.

For us, investing in a system that supports multiple companies, a range of operators specialized in certain operations, is necessary to ensure we further this industry, in a cost-effective way but one that supports the best safety outcomes.

Wing is a pioneer in drone delivery, UTM technology and collaboration

Partnerships

Wing has a very highly automated aircraft. It knows how to fly itself, it knows how to get from A to B, it knows if it is healthy or not. That automation complements our UTM work. We recognized that if we’re going to have a fleet in the air, we’re going to need a way to manage it. To do that, we built on concepts like strategic conflict detection. We make sure that before our aircraft takes off, that it’s conflict-free and closely aligned with the ASTM standard. We’ve been doing that for almost five years now.

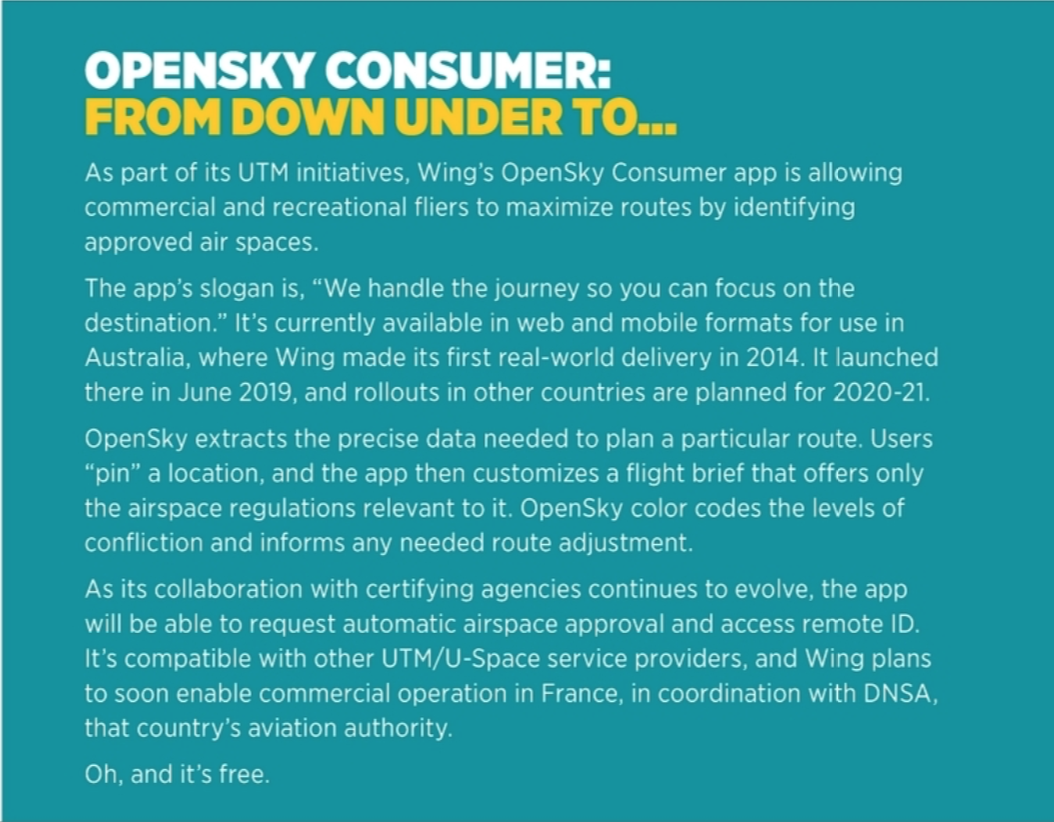

We’ve also been very excited to publicly launch our capabilities. Last year, we launched an approved public safety app in Australia that enabled operators to know where they can and can’t fly [see sidebar]. It helped set the precedent for other apps to come. We took a single app to market, plus working with the regulator on a framework to build a lot of LAANCs and open it to three other companies [LAANC stands for the Low Altitude and Notification Capability that provides automatic authorization to access controlled airspace at or below 400 feet through FAA-approved UAS Service Providers/USS]. We’ve continued to take some of that learning from Australia and are now working with France and the U.K.

We are part of the European U-Space program. We’re working with them to have a LAANC-like ecosystem with multiple service providers, and looking to going beyond the services supported by the ASTM standards like remote ID and strategic deconfliction. We’re bringing the same capabilities and technologies to help the U.K. to set up an ecosystem with multiple providers, and helping them to improve it, to prove out the concepts of operations in the U.K. context.

It’s really great to see how the momentum of an ecosystem can quickly take root. In Australia, it took basically less than six months to have an ecosystem of apps and also the acceptance of concepts more broadly across many areas of operations. We’re also working very closely with Switzerland. By the end of the year, they’re going to be launching a national remote ID.

These are all spots where our technologies will have some helpful tools for regulators to help launch and manage these ecosystems, but also bringing our technologies and our open skies systems to support drone operators in a range of ways as well.

InterUSS Open Source Project

If you think of UTM a bit like the internet, you need to have ways to know who to talk to and when as part of the work that you’re doing. The ASTM standard has defined something they call the Discovery and Synchronization Service, which in a rough way is kind of DNS [Domain Name System] for UTM. We helped pioneer that concept in some of the early NASA trials, supporting that capability and proved it out in TCL 3 [NASA’s Technology Capability Level testing—safe space] and brought it more into TCL 4 [urban area/delivery operations]. The InterUSS platform moved to an open source but standard-compliant version of that part of the ASTM standard for USS.

We were very excited to see it launch in The Linux Foundation in August of last year, and for it to be available to the entire community. Open source in aviation is a critical component for us to see rapid innovation and diversity.

InterUSS has taken off: it’s now in the U.S. in both UPP [The FAA’s UTM pilot program to define the initial industry and FAA capabilities required to support UTM operations] and UAM [urban air mobility] activities. We’re seeing multiple companies using it, and we’re seeing it adopted and leveraged in multiple spots around the world.

Strategic Deconfliction

Given where we are today, we’re very focused on strategic deconfliction. “Strategic” in the sense that you have an intent that you’re sharing. We think that’s important for lots of reasons. Drones don’t fly in standard ways; the position of a drone is not necessarily as well-understood as the position of a [manned] aircraft. “Intent” lets you know where an aircraft’s going to go; it lets you have a further-out trajectory of where the drone’s flying. You can go ahead and have more optimal use of the airspace; you know where they’re going, so you know how to specifically avoid that.

We also know that each drone flies different, so the type of performance, how close they fly to their intended path, all that is different. We needed a way to incorporate that. And so, sharing this operational strategic intent is a way of achieving that. You get more efficiency, more effective operations and you still get a level of safety.

We do see over time that there is a “defense in depth” approach that could exist, and for us we’re excited to look at, for example, the range of drones that is incorporating ADS-B onboard for deconflicting with manned aircraft. [Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast uses satellite navigation to determine and broadcast an aircraft’s position, allowing it to be tracked].

We do see tactical cooperative separation with manned aircraft. But for us, interoperability only works if you have a harmonized approach that works between companies and between industries and across the country, and globally.

We’re starting global harmonization. You don’t want to be in the realm of cellular, where you couldn’t take your phones to different countries. We want to start early and often with this global harmonization and thinking about global standard versus regional standards to make sure we’re not in that situation. Because drones do travel. We need to make sure that operators have a fairly consistent and holistic experience, and global harmonization is a key path to get there.

Innovation

As we react with communities in new and better ways, we need to continue to learn and improve. More than that, we have performance-based regulation that enables us to continue to get better. One of the things we learned in Australia is that because there wasn’t a prescriptive way on how you flew on the routes, we had to innovate and go ahead and change the way we flew very quickly. Now we don’t have a single, deterministic answer for routes; they’re more random, and we found that’s better way of engaging the community. If you would have asked anyone in aviation if that would have been their path, they would not have picked that as the answer. You need that innovation to react to the world.