Reporters are always looking for just the right picture, that perfect bit of film, to illuminate the size and scope of a story and captivate their audiences. So it only makes sense that news organizations—including major players like CNN, Sinclair Broadcast Group (SBG), BBC News, and Canadian Broadcasting Corp. (CBC)—are increasingly turning to unmanned aerial systems (UAS) to capture video for their broadcasts. They’re able to shoot images from perspectives not possible before, often leading to visually stunning packages.

“If you need to put something in context in a landscape, if you’re covering something that has a large spatial extent where describing it is difficult or photography from the ground is difficult, a drone is the machine for you,” said Matthew Waite, professor of practice at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Drone Journalism Lab. “Even if you’re getting just 100 feet in the air, it can change your perspective on a news event.”

To help ensure reporters are well versed in how to safely, ethically and legally use this new tool, journalism schools are starting to offer programs that focus on drone journalism, while organizations like the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA), the Poynter Institute and Google News Lab are partnering to provide training as well. Even some of the Federal Aviation Administration’s test sites are getting into the mix, with Virginia Tech offering training to a number of top news organizations over the last few years, including SBG.

Drones are proving to be valuable newsgathering tools, and it’s not farfetched to expect them to someday become standard equipment for camera crews. And while they’ll never completely replace helicopters—the perspectives they capture are just too different—UAS do provide more intimate, compelling views at a fraction of the price.

Of course, just like with any other industry looking to implement drones commercially, the benefits don’t come without challenges. Journalists can’t simply buy a drone at a big-box store and expect to use it out in the field the next day. Newsrooms must invest time in policies and training, in becoming familiar with the regulations and even in educating the local community about their intentions before planning that first flight. But once news organizations put in the time, they’ll find they have a tool that helps them do storytelling differently, and that might eventually open up new possibilities in investigative journalism and enable them to serve as even better watchdogs.

Newsroom Applications

Drones can be deployed to help tell a variety of stories, and enable journalists to capture video in areas they can’t reach on foot or by car. Shooting video from a drone after a flood, for example, shows the audience exactly how widespread the damage really is, said Jeff Rose, Chief UAS Pilot for SBG. They can see the washed out roads and the devastation, and understand it isn’t safe to try to drive across town.

Covering car accidents, mapping out a crime scene, flying over building demolitions, taking images of new construction and documenting damage from storms and natural disasters are among the many examples of how newsrooms use drones to give their viewers more context (See Telling the Story page 24).

“That perspective has the power to open your mind to how big something is,” Waite said of the benefit for the audience. “It doesn’t have to be a world-changing disaster. It’s just the ability to put an image in front of somebody that gives them the sense of how big it is. That can really change their perception of the story.”

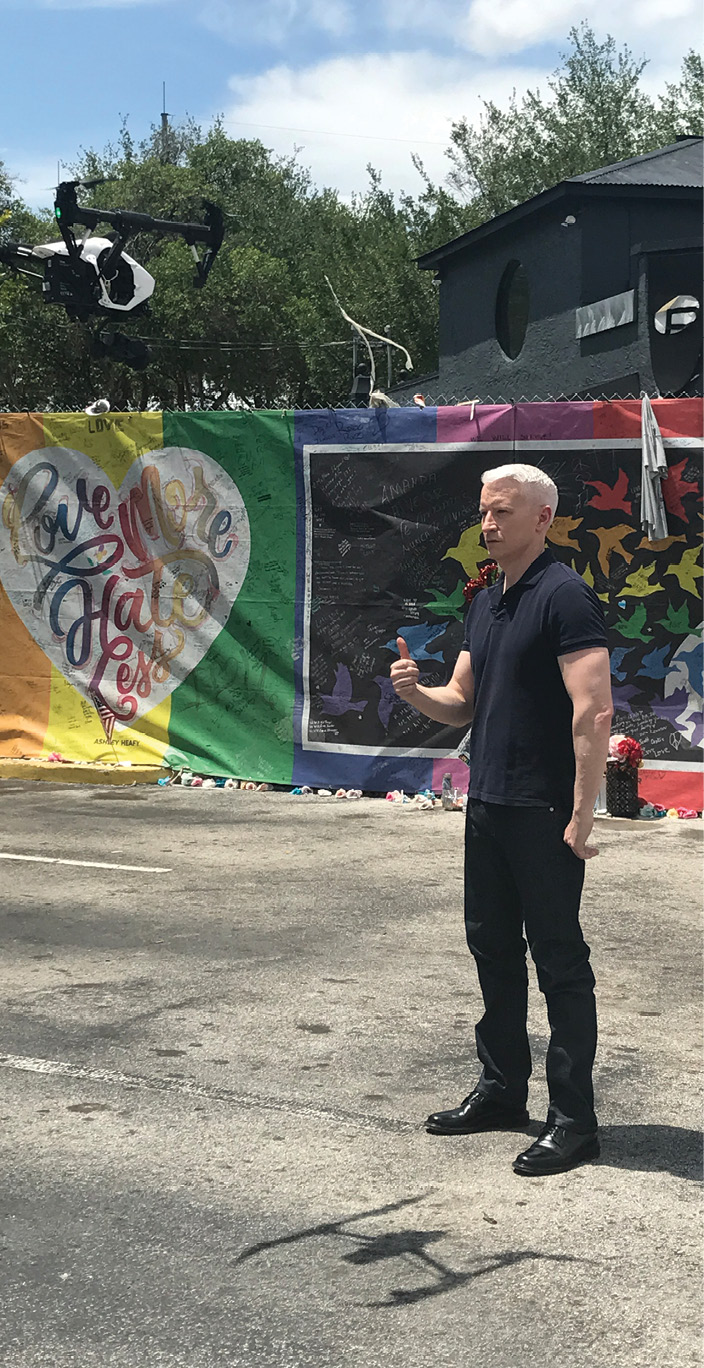

Because these flights take planning and require authorization if the UAS needs to fly in restricted airspace, covering breaking news can be challenging, said Greg Agvent, senior director, CNN Aerial Imagery & Reporting for CNN Worldwide. CNN’s drone program, CNN Air, which marked its first year in August, has flown more than 100 unique UAS missions and has logged almost 200 flight hours. Most of the footage captured during these flights is used for enhanced storytelling, with only about 20 percent of the flights deployed for newsgathering. The footage is used by both Turner and its parent company Time Warner.

Some journalists opt to use their UAS as a second camera, said Todd Ofenbeck, a photojournalist and UAV Pilot in Command for Waterman Broadcasting’s NBC-2 in Fort Myer, Florida. While Ofenbeck deploys his drone a few times a week to capture those aerial shots, another authorized pilot for his company flies his for just about every story, as long as he isn’t in restricted airspace. He uses the Mavic from DJI, a small drone that is easy to transport and to deploy for panning shots. Once he’s done, he simply folds it up, puts it back in his pocket and moves on to the next story.

Drones also make it easier to take more complex, moving camera shots, Waite said. So instead of the static news video audiences are used to seeing, that video can now have a more cinematic quality.

The SBG stations use the DJI Inspire 1 and the DJI Inspire 2, Rose said. The Inspire 2 features a detachable camera lens, giving them the ability to attach a zoom lens to capture what he describes as more natural newsgathering shots, such as a wide shot of a scene.

“We’re increasingly finding uses we didn’t anticipate,” said Al Tompkins, senior faculty for broadcast and online at Poynter Institute. “A lot of drone video isn’t in the sky, it’s six or eight feet above the ground. They’re being used as movable tripods. You get incredibly steady shots even while the aircraft is moving. It’s much steadier than a handheld camera. Instead of taking a walking shot, photographers can shoot with the drone. If you’re shooting video in a corn field you could stand on a ladder or you could fly over it and get really interesting, beautiful shots without interrupting anything on the farm.”

When the team at NBC-2 first invested in a drone, they wanted something that would make it possible to broadcast live, Ofenbeck said, which is why they decided on the DJI Inspire 1 Pro. At the time, it was one of the few UAS that featured a video output on the controller that they could connect to the live truck. The signal isn’t great, however, and the video tends to break up—so while they have the ability to go live during a news event, it isn’t a priority.

Before deploying a drone, it’s important for journalists to make sure they actually add value to the story, said Bill Allen, assistant professor of science journalism at the University of Missouri. The temptation is to fly drones for every story just because they’re available, but if all you get is a pretty picture that doesn’t move the story forward, then it probably isn’t worth it.

“The drone collects video that supplements the story,” Rose said. “The whole story isn’t told with a drone, but in certain cases there are great pictures from a drone that help to tell the story with a big benefit.”

Change in Coverage

Incorporating drones into reporting does tend to impact the way newsrooms cover stories. For WBNS 10TV News Operations Manager Timothy Moushey and the rest of his Columbus, Ohio team, it has become part of their thought process during the morning meeting. When managers, reporters and producers talk about that day’s news, they also think about how they can best use the drone to enhance their storytelling. They deploy UAS multiple times a week, and recently flew to capture video of flooding that resulted from a heavy rainfall, and to cover a promotional event at the news station.

“It changes the way we think about approaching a story,” CNN’s Agvent said. “Drones aren’t right for every story, so it challenges our producer to story board and to think about how it adds value. If we can’t answer how it enhances the story we’re telling, then we tend not to use the drone. For every 100 requests we get, we fly 60 percent and we say no to the other 40 percent. This is not the flavor du jour. It’s not a gadget. It’s a really effective tool in communicating what we need to communicate to our viewers and users.”

These flights require a lot of planning, Moushey said, so the earlier they can get requests to deploy a drone for a story the better. As soon as they receive a request, the team consults a map to see how close the assignment is to the airport, and will communicate with air traffic control to let them know they’re flying.

“It can be a challenge with the speed of news. You can’t always get into locations ethically and safely,” Moushey said. “We always keep that in mind when planning flights.”

When CNN decides to fly a drone for a story, the team then has to determine which drone is best for the job, Agvent said. It’s not one size fits all when it come to the aircraft’s capabilities. Their fleet is made up of very small drones that are easy to deploy, tethered systems and higher end systems for the times when production requirements call for a more stable platform.

No matter what drone a newsroom uses or what story they’re covering, it’s important for the team to listen to the pilot in command, said Mickey Osterreicher, general counsel for the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA). If the pilot says it’s not safe to fly, whether it’s because of weather, airspace restrictions or any number of other reasons, the rest of the team has to respect that decision, just as they would a pilot of a manned aircraft they wanted to deploy. Simply put, newsrooms need to develop a culture of safety surrounding their drone program.

The SBG stations follow a 22 page operations manual that includes FAA guidelines as well as company-wide operations guidelines for pilots, Rose said. The manual covers all their setups in detail and includes checklists that help with pre-flight planning. If any issues come up during or before the assignment, pilots can refer to the manual for guidance. This ensures everyone in the company is on the same page, enabling the news team at every station to operate professionally and safely.

“There’s a real temptation to believe the drone is new and different and changes things completely. That’s not really true,” Waite said. “It’s an extremely useful and flexible tool but it’s just a tool. There still needs to be a story. There still needs to be humanity. You can’t just bust out a drone and get three minutes of aerial video, stick it on air and call it a day. It requires a lot more forethought than chucking it in a bag and heading out to the story.”

Preparing for Drones

As with any other sector of users, journalists need to learn how to properly fly UAS and to understand the FAA regulations, Osterreicher said. They need to invest in insurance as well as put the proper policies and procedures into place, and that includes maintaining the drone and keeping flight logs.

That’s why training programs have started to pop up, as well as courses in journalism schools.

Training at Virginia Tech, an FAA-designated UAS Test Site, consists of a day of classroom work focused on Part 107 rules and two days of hands-on flying, said Matt Burton, flight operations manager. Even though the FAA doesn’t require them anymore, students learn about the role of visual observers, how to perform basic maneuvers to get a feel for what UAS can and can’t do, and have the opportunity to try out different use cases.

This year, Poynter Institute partnered with the Drone Journalism Lab at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, NPPA, The Google News Lab and DJI to provide workshops for journalists. This training was designed to help reporters prepare for the Part 107 exam as well as teach them ethics and drone law. Some local and state governments are trying to regulate airspace, Osterreicher said, which is a challenge drone journalism news teams need to be aware of.

The three-day course also teaches journalists they can do so much more than just capture aerial video with a drone, Tompkins of Poynter said.

“We’re teaching them about 3-D mapping and 360 degree photography using drones,” Tompkins said. “Everyone knows you can hover over a fire or flood and get pictures. We’re trying to help them think about advanced ways they can use the data, such as marrying it with 3-D mapping technology.”

Before any of the SBG stations launch a drone program, Rose goes out to configure the aircraft and to make sure pilots have the proper training, he said. They also schedule a community outreach meeting to talk with police, firemen, EMS, local officials, air traffic control—basically anyone they might come in contact with while operating a drone—to show them the equipment and to determine the best way to communicate with them about flights, which includes sharing cell phone numbers and making sure the assignment desk lets the public information officers know someone is on the way with a drone.

Proper communication with emergency responders is also an important part of Virginia Tech’s training, Burton said. One of their staff members is a medevac pilot, which helps give trainees a unique perspective on potential problems drones can cause during emergencies, including keeping medevacs from landing. It’s important for operators to know to give way to manned aircraft and to never impede emergency aircraft.

A Focus on Safety

For Agvent and the team at CNN, safety is not a goal—it’s a requirement. They take risk management very seriously, Agvent said, which means requiring pilots to complete training that’s beyond what’s necessary to earn their Part 107 certification. CNN has worked closely with the FAA for the last few years through the Pathfinder program, helping lay the foundation for responsible, safe UAS operations for news coverage.

CNN has about 10 trained pilots, two of which are full time and have their own private pilot’s license, Agvent said. They know how to communicate with manned aircraft if it ever becomes necessary. They also perform an IRA, or an initial risk assessment, before every flight and ask if the pilot and the UAS have the ability to perform the mission safely. If the answer is no, they work to mitigate the risk or keep the aircraft grounded.

“You have to hold yourself to a higher standard,” Agvent said. “That means committing to training, and maintenance and flight planning and purchasing the best equipment.”

The nearly 30 SBG stations that deploy drones still require two person operations to help ensure safety, Rose said. That way, there isn’t a pilot flying a drone and operating a camera at the same time. The pilot in command watches the drone and the visual observer keeps on eye on the video feed to make sure the shot is centered and looks as it should. Pilots also have the authority to say no to flying if they don’t deem it safe, without getting pressure from their manager or news director to fly anyway. All SBG pilots receive training at Virginia Tech.

Flying safely also means working with other news stations while on assignment, Rose said.

“Competition goes out the window when it comes to safety,” he said. “If we show up at a scene where a station from across town is flying a drone, we talk to them to establish boundaries before we set up. We tell them what we intend to do. That’s crucial to successful operations. We’re all going to be flying at the same places and at the same time.”

Other Challenges

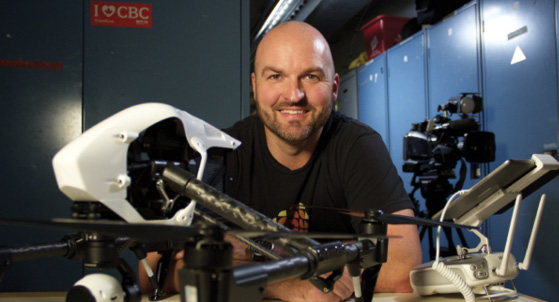

No matter where news organizations fly, the teams have to make sure they do everything by the book, said Ed Middleton csc, videographer

and UAV operator for Canadian Broadcasting Corp. (CBC). That means following regulatory guidelines as well as guidelines put together by their organization.

News teams also have to make sure they fly legally, ethically and that they don’t violate any privacy laws, said Morwen Williams, head of Newsgathering Operations for BBC News. They have to let people know they’re filming them and to ask permission if they need to fly over or from someone’s property to cover a story.

“I don’t shoot anything I wouldn’t shoot from the ground,” Ofenbeck said. “Any of us who shoot for news understand how to maintain privacy. We don’t intrude on people or hover over property without an absolute reason to be there.”

There are some grey areas when it comes to privacy laws, Waite said, which is why the best thing to do is ask permission before flying over a homeowner’s land.

Airspace restrictions also present problems, Burton said, especially the regulation that prohibits flights over people. That’s especially challenging for journalists who cover large cities, and does limit the type of stories news organizations can cover via drone.

“We end up flying in a limited fashion,” Rose said. “The challenge for our individual pilots is to look at what they want to shoot when they get to a scene and then determine if there’s a safe place to launch and fly. They also need to find a secondary landing zone. That’s all part of the setup, checklist and preparation.”

CNN does have a waiver to fly over people, Agvent said, and the team knows how important it is to conduct those flights safely. He wouldn’t take a system off the shelf today and fly it over a large crowd to cover a news event; he just doesn’t feel the predictability is there yet. CNN looks at systems that have ballistic parachutes to slow down the descent in an emergency situation. Agvent also likes propeller cages, and said he works with manufacturers to make sure they’re available. Audible warnings also can be helpful in an emergency situation.

The Future

The drone industry is still very young, and as the technology evolves and the regulatory landscape becomes clearer, even more capabilities for newsgathering will emerge. The systems will become even smaller and easier to transport, and there will be more opportunity for live broadcasts, investigative reporting and watchdog journalism. Eventually every news photographer will have a drone, Moushey said, with the ability to easily deploy a system if a story calls for it.

“Value added images are fine but the real deal is how they can help journalists do their watchdog roll,” Allen said. “It’s going to take some experience and creativity to really think about how that’s going to work. That’s also the fun part of this. What are the applications? What are the stories we can be looking at?”

Through augmented reality, Agvent sees the ability to super-impose live location based information over drone footage, such as street names and buildings. This could add context and understanding to a flooding story, for example. Manufacturers are also starting to recognize the value in developing UAS for specific industries, a trend he expects to continue.

Reporters will become more and more comfortable deploying drones and determining the best stories to cover using the technology. It might get to the point where just about every story has a drone shot, Waite said, but eventually, once the newness wears off, we’ll start to see even more creative uses for drones. The real value will come when reporters start to gather data that will be mapped or tracked over time. They’ll have access to on-demand high-resolution information, which could prove to be really powerful for certain stories.

“The real frontier with drones is in data and investigative journalism,” Waite said. “Some newsroom is going to win a huge prize with this. That’s the next big thing that’s going to happen. A Pulitzer will get won and it wouldn’t have happened without drone photography.”