The North Carolina Integration Pilot Program (IPP) team plans to use drones for faster and more economical delivery of medical samples, emergency supplies and takeout meals as well as for completing safer and more efficient inspections of infrastructure.

There is nothing routine about flying drones over people, beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS), at night and through bad weather. But that may change under the FAA’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Integration Pilot Program (IPP). North Carolina’s IPP team, led by the state’s Department of Transportation (NCDOT), is working to conquer these obstacles and provide the FAA with the data it needs to move forward with much-needed rulemaking for complex flights.

Basil Yap, UAS program manager for NCDOT, said IPP has brought about a total change in how the agency interacts with the FAA. Instead of submitting waivers and waiting, there is now a dialogue. “Now when we submit a waiver the FAA has an expectation of what they are going to see in the safety case,” he said. “Dialogue expedites the process.”

DRONE DELIVERY OF MEDICAL SAMPLES AT WAKEMED

Even before North Carolina was chosen from more than 140 applicants to be one of the 10 IPP teams, WakeMed, a large local provider, had been working with drone delivery supplier Matternet.

Dr. Stuart Ginn, medical director of WakeMed Innovations, surgeon and former aviation professional, could see the potential for drones to address a growing problem for the hospital—delivery of medical samples to labs across an expanding health care system. Third party couriers who transport medical samples represent a costly line item for the hospital and often leave doctors and patients waiting hours for lab results. “It really wreaks havoc on our operations,” Ginn said.

WakeMed and Matternet used a framework they had already developed in the application for the IPP. At first, they envisioned using drones exclusively for urgent needs, but they soon realized the system could accommodate most of their needs.

In a fully implemented system, most flights would fall into the 10- to 15-kilometer range. While WakeMed is still modeling what the final system will look like, it’s clear the cost savings will be significant. Equally important are the faster turn-around times.

“We’re looking at significant improvements in lab turn-around time, which will help clinically,” Ginn said. “While it can take several hours for samples to get to the lab using the current methods, drones can transport samples in just minutes.”

FIRST FLIGHTS

The first drone delivery test flights at WakeMed were conducted in late August, over people and within visual line of sight. Simulated medical packages were transported from Raleigh Medical Park, located across from the WakeMed Raleigh Campus, to the main tower at the hospital. The three-minute flight over a busy road successfully demonstrated the efficiencies of drone delivery. The safety case for flying over people had to prove the reliability of the aircraft and that the chance of failure was low, Yap said. The flight pattern minimized the time spent over people to approximately 20-30 seconds. Take-off and landing areas were secure. In the event of a failure, a parachute would be deployed. The next step will be flights of longer distance and BVLOS.

“The big focus is going to be to detect and avoid,” Yap said. “How do we detect and avoid other aircraft while we are flying beyond visual line of sight? We have been fortunate to have partners such as Zipline, Flytrex, and Matternet, who have a lot of data and flight hours overseas.”

While these are Matternet’s first flights in the United States, the company has flown more than 1,800 medical delivery flights over Switzerland. “Our company and technology are fundamentally optimized to support applications within urban health care,” said Ben Hansen, business development executive for Matternet.

To win FAA approval, the current concept of operations for the WakeMed deliveries calls for a safety pilot and onsite technician to be on hand for autonomous flights, with the goal of moving toward full automation.

“We hope that in the not too distant future we will be able to implement a fully automated technology stack (drone and landing infrastructure) and can start removing those operators,” Hansen said.

“The transformative power of the drone has to do with reimagining the supply chain,” he said. “We know the speed at which we can transport is tremendously faster and more economical than roadway transportation.”

EMERGENCY MEDICAL DELIVERIES IN RURAL NORTH CAROLINA

Another objective of North Carolina’s IPP program is emergency medical deliveries. Zipline is the drone delivery partner that will test distribution of emergency medical supplies to remote areas of North Carolina. After orders are sent via text to Zipline, supplies will be expedited from a central distribution center to the remote location in a matter of minutes. The packages will be deployed via parachute to a designated drop area. The Zipline fixed wing aircraft is designed for flying longer distances and BVLOS.

Zipline is fully operational in Rwanda and has been successful flying in a variety of weather conditions, but, Yap said icy conditions can still ground drones.

Drones encounter different hazards in rural and urban deliveries. “While rural areas have lower risk due to low traffic volume and fewer people,” he said, “there are still potential hazards from crop dusters and military training routes, as well as other obstructions, such as cell towers. In contrast, urban flights encounter densely populated areas, increased air traffic and a variety of obstructions,” Yap said.

T-mobile will ensure drone flights maintain connectivity. The North Carolina team hasn’t had any issues with getting a cellular signal at 200 feet. Instead, it is a matter of making the sure the drone attaches to the closest signal. There is also a secondary communications backup.

FOOD DELIVERY IN HOLLY SPRINGS

NCDOT is also overseeing the testing of food delivery by drone in Holly Springs, N.C. For these tests, they will use Israeli drone delivery company Flytrex. Flytrex has conducted drone delivery in Iceland and is delivering food to a golf course as member of the North Dakota IPP team.

Flights over people and traffic (but not BVLOS) were expected to begin at the end of 2018. Customers will order from participating restaurants through a mobile app and, in certain locations, will be able to select delivery by drone. The first flight will carry food from restaurants in a shopping center in Holly Springs to a local park. To address privacy concerns, the drone will not fly over homes or be equipped with a camera. Drones will lower the food to the ground or to an attendant via a wire drop system. A unique code will allow customers to access their food.

“The safety case is going to be easier if there is one route versus multiple routes,” Yap said.

The drone delivery is expected to take about five minutes, compared to about 22 minutes by car. For the first few months, an attendant will manage the drop site.

ADDING INFRASTRUCTURE INSPECTION

In a new development, NCDOT requested and received permission to expand its initial IPP plans to include infrastructure inspection. NCDOT will be using drones to monitor the quality of new construction projects, as well as existing roads, bridges, ferry terminals, airports and rail facilities.

Cameras mounted on drones provide a detailed view without putting someone on a hoist, lift, or bucket truck, greatly increasing worker safety. A key focus will be on the linear inspection of roads.

While NCDOT has previously used drones for infrastructure inspection, under the IPP, they want drone inspections to become routine.

UAS TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT

UAS traffic management is key to the expansion of drone operations and AirMap will be offering UAS Traffic Management (UTM) services to the North Carolina IPP and five other IPP teams. Bill Goodwin, head of AirMap’s legal and policy teams, envisions a future where multiple UTM systems manage hundreds of thousands or even millions of flights a day. He says that while the concept of one-to-one air traffic management works in the current environment, it will not be enough to manage the complexities of a world served more fully by drones.

“A profusion of drones can bring enormous benefits but requires an enormous amount of services to ensure they don’t run into each other, don’t annoy people on the ground, don’t cause a safety risk to people in the air or on the ground, and deliver commercial benefits as promised without violating the privacy or private property rights of the communities where they are operating,” Goodwin said. “To balance all of that, you need a tool like UTM that allows for that complexity and solves it safely.”

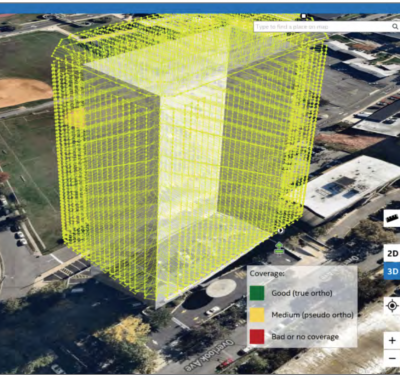

In North Carolina, an AirMap UTM system will integrate information about who else is flying in the airspace, whether it’s commercial aircraft, helicopters or other drones. It will help operators perform BVLOS flights by providing information on airspace and ground conditions. A UTM system can also alert operators or reroute drones to avoid an area that has become unsafe.

“By integrating data from cell phone providers or other IoT (Internet of Things) networks you can get a dynamic heat map of where people are and you can route your drone around crowds of people and put it in the least risky environment,” Goodwin said.

PrecisionHawk, another North Carolina IPP partner, brings expertise in BVLOS flights. As part of the FAA’s Pathfinder project, they were involved in outlining a comprehensive safety case and standards for flying drones BVLOS. Flying BVLOS is seen as the key to many commercial drone applications. PrecisionHawk’s focus is unmanned traffic management with the low altitude traffic and airspace safety platform (LATAS).

Allison Ferguson, PrecisionHawk’s director of airspace research, believes IPP projects represent a real leap forward for the industry. “Most of FAA’s Pathfinder research was done in a rural setting,” Ferguson said. “Now we are operating over people, in controlled airspace and using a lot of automation. The IPP timeline is quite short from a research perspective.” IPPs have just 24 months to achieve commercialization and provide a blueprint for local businesses thatwant to take on more complex operations.

COMMUNITY OUTREACH

An important component for IPP teams is public outreach because information on public sentiment surrounding drones is something the FAA currently lacks. The IPP could be a good test of public sentiment on drones including what applications they will and will not welcome. Beyond safely integrating drones into the airspace, public feedback may be the most important result of the program.

“We really wanted to engage with the community,” Yap said.

However, after two public outreach events primarily attracted drone enthusiasts who want to learn more about the industry, NCDOT realized they will have to alter their strategy. Their target audience is average citizens who don’t necessarily have an interest in drones.

“We didn’t expect that we would have to reevaluate the way NCDOT has traditionally done community outreach,” said James Pearce, public relations officer, North Carolina Department of Transportation Aviation. “We are looking at new ways, through social media and other methods, to get the public educated, more engaged and more invested in this project.”

Ginn believes seeing drones in operation will have a positive impact. “Once people actually see the technology, and watch it operate, their opinions of it changes very rapidly.”