Urban air mobility often conjures images of flying cars shuttling passengers around. However, autonomous air transport of cargo promises to be as, or even more, important as an element of UAM.

Cargo drones powerful enough to carry people—and even cars—are now under development and may get certified before any flying car designed for passengers will. They may even pave the way for commercially viable flying cars by showing how safe and useful such large craft can be.

“I think flying cargo is a stepping stone to flying people,” said Dave Merrill, co-founder and CEO of Elroy Air in San Francisco. “The FAA likes to take a ‘crawl, walk, run’ approach, and flying cargo with an autonomous aerial system is much lower risk than flying humans. I definitely see that with air-taxi-sized cargo systems, there is no way that will not come first, and they can help gain operational maturity for passenger flights.”

Not that Merrill and others are developing cargo drones simply as a stepping stone to flying passengers. “Never say never, but cargo is such a big business, and there is so much work to be done in it,” Merrill said. “I can build a 50- or 100-year business just doing cargo.”

HEAVY LIFTING

Most research into delivery drones focuses on relatively small payloads. For instance, in Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos’s 2013 interview with “60 Minutes” he noted the drones Amazon was developing aimed to carry packages up to 5 pounds in size, which he said covered up to 86 percent of the items the company delivered.

In comparison, Sabrewing Aircraft in Camarillo, California, is now developing an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) capable of flying literally tons of payload. “Sabrewing is building the first heavy-lift long-range autonomous cargo aircraft in the world, which includes the ability to travel from any airfield, or even no airfield,” said Ed De Reyes, chairman and CEO of Sabrewing.

The Rhaegal is roughly 60 feet long and 14 feet high, with a wingspan of about 60 feet. The aircraft is powered by two gas turbines, and has a cruise speed of about 205 miles per hour and a range of about 1,120 miles.

“We weren’t interested in batteries or hydrogen or fuel cells—we didn’t want customers to invest in extra technology for one kind of aircraft,” De Reyes said.

Sabrewing’s Rhaegal is capable of both conventional flight and VTOL (vertical takeoff and landing). Conventional fixed-wing aircraft are far more aerodynamically efficient than multi-rotor aircraft, giving them longer ranges, greater endurance and higher speeds for similar amounts of power. On the other hand, multi-rotor aircraft not only can hover and fly at low speed, but can also take off and land vertically without runways or complex launch and recovery devices. Hybrid aircraft capable of converting between fixed-wing and VTOL flight are becoming increasingly popular for a wide range of applications.

The Rhaegal can carry a maximum payload weight of 5,400 pounds during VTOL flight and 10,000 pounds during conventional flight. The aircraft is designed to fly in nearly any weather, including heavy fog, and Sabrewing is currently working on certifying it for the capability of flight into known ice.

When it comes to serving cities, De Reyes suggested the Rhaegal could help shuttle cargo from logistics bases such as the one near San Bernardino, California, to sites in Los Angeles and elsewhere in Southern California in cases where disruptive weather conditions would ground conventional aircraft and snarl ground traffic as well. “The Rhaegal can take off with cargo, drop that off, load more on and do that multiple times before it has to refuel,” De Reyes said. “You can also imagine just-in-time delivery from factory to factory or supplier to factory, to help an assembly line that would otherwise go down due to lack of parts.”

All cargo gets loaded through the Rhaegal’s nose. No special equipment such as a forklift or a pallet jack is needed to load or unload freight. It is designed to accommodate two LD-1 unit load device (ULD) containers, or four LD-2s, or two LD-3s, which are all “the common cargo containers that you would find in the lower depths of a cargo aircraft,” De Reyes said.

The Rhaegal possesses four ducted fans it can tilt for conventional or VTOL flight. Its wings fold to allow the Rhaegal to take off, land or get stored in tight spaces. “They can actually fold in flight during hover,” De Reyes said.

The aircraft is designed for semi-autonomous flight. “It is remotely operated, and if for whatever reason it loses satellite communications with its remote operator, the aircraft can continue its mission, and land even in remote places without having to have the operator in the loop,” De Reyes said. It possesses eight different detect-and-avoid sensors, and maintains six command and control links—two voice, two data and two position channels—to help reduce the chances of linkage loss.

All in all, Sabrewing claims a greater payload and range than common small-crewed freight aircraft such as the Beechcraft 1900, Cessna SkyCourier or Cessna Caravan, as well as 70 percent less operation costs and 50 percent less maintenance costs than those airplanes—not to mention how those fixed-wing craft need runways. At the same time, Rhaegal’s ability to shift to wing-borne flight gives it greater range and payload capacity than comparable helicopters, De Reyes noted.

Sabrewing plans for the Rhaegal to enter service in 2021.

PACKAGE DEAL

In comparison, Elroy Air aims to quickly deliver smaller packages than Sabrewing’s pallets, albeit still with significantly larger payloads than conventional delivery drones. The company’s Chaparral aircraft is about 28.5 feet long and 7 feet high, with a roughly 26-foot wingspan, and has a maximum payload of 300 pounds.

“Customers have requested 300 pounds of cargo because it enables an additional level of flexibility to deliver goods when and where they are needed,” Merrill said. “Most of the packages that we are asked to move are less than 15 pounds. However, when you are able to consolidate to move 10 or more packages at one time, that can fulfill the orders of multiple customers. This additional layer of flexibility means that the customer can deliver products as they are available without needing to wait for a truck or plane to be full.”

The Chaparral is capable of both fixed-wing and VTOL flight, possessing one horizontal pusher propeller and six vertical rotors that lock forward during conventional flight. It has a cruise speed of 130 miles per hour, meaning it can complete a 100-mile flight in less than an hour, “which can be up to three times faster than trucks,” Merrill said.

With its hybrid electric powertrain, the aircraft has a range of three hours and about 300 miles with a full payload in its roughly 40-pound cargo pod. “The most requested mission for us from customers is over 100 miles,” Merrill said. “Since our system would need to be able to deliver goods both ways without fueling, our 150-mile round trip capabilities exceed their requests.”

The Chaparral’s range also help it minimize delays cargo deliveries would experience because of airports. “Airports tend to be a limitation for today’s aerial delivery. They typically add an additional step in the process and limit where shipments can be expedited,” Merrill said. “Our systems enable shippers to fly directly from one location to another without the relying on additional airport infrastructure.”

Merrill added that with a range of 300 miles, customers have told him the Chaparral might rival feeder aviation—that is, the smallest regional airlines, which feed packages to and from airports served by larger aircraft—“and be up to five times faster than their current solutions.”

Elroy Air designed the Chaparral to have autonomous ground operations, including taxiing, as well as loading and unloading of modular cargo pods. “We want to keep the vehicle in motion, operating without waiting around,” Merrill said. “The aim is high throughput and high efficiency with minimal operator input.”

The company has developed technology it has not yet described publicly for the aircraft to identify, locate and navigate to pods to which it is assigned “and engage the pod grasping, lifting and latching robotic system to get the pod connected to the aircraft,” Merrill said. Cheap, lightweight, reusable components on the pod itself help assist in these operations, he added.

Elroy Air sees the main application for the Chaparral as express delivery, “to improve the reach and performance of express logistics in and out of urban centers,” Merrill said. Specifically, the aircraft is designed for “middle-mile” logistics, such as deliveries from airports to distribution centers, between centers or from centers to parking lots for handoffs to last-mile trucking. “We do not expect to deliver ‘last mile’ to the homes of individual consumers, as last-mile is better suited for smaller systems and comes with complexities around safety in handing off cargo to everyday people,” Merill said.

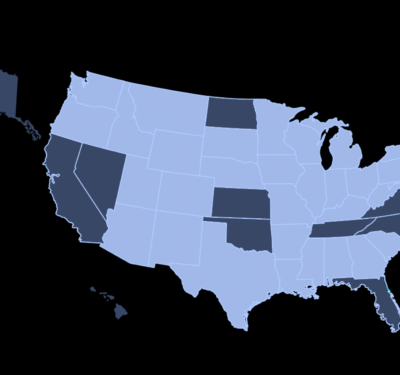

Merrill does not see Elroy Air’s first deployment going in and out of urban areas. “We are likely getting an operating certificate for more remote missions first in more austere, less populated areas,” he said. “As we show a track record there, we will hopefully be able to secure permission to fly over urban areas.”

Serving remote areas may prove valuable beyond being a stepping stone to urban missions. “Amazon is showing everybody what is possible in terms of ratcheting up delivery speed, but 1 billion people in the world do not even have access to good roads, and geographical features such as mountains and valleys can also make it hard for areas to achieve really good logistics,” Merrill said. “We hope to help provide high-performance logistics in places where traffic or other factors make it hard to do by any other means.” To that end, Chaparral can deploy from the ubiquitous Lockheed C-130 Hercules cargo plane to provide humanitarian aid, disaster relief and rapid resupply.

Elroy Air flew a full-scale demonstrator of the Chaparral from last August to October. The company aims to have the aircraft enter service in 2022, Merrill said.

POD TRANSPORT

Aviation pioneer Bell Textron in Fort Worth, which built the first aircraft to break the sound barrier and was the first company to certify a commercial helicopter, is now developing all-electric cargo drones it dubs “autonomous pod transports,” or APTs. In principle, this series of drones could get scaled in size to carry anywhere from a few dozen to a few hundred pounds.

The APT model the company is currently developing is the APT 70, which can fly at an average speed of 100 miles per hour. With a payload of 70 pounds, it has a one-way range of 35 miles and can quickly recharge with a battery swap.

The APT 70 stands 6 feet tall on the ground, sitting on its tail while on at rest, with a 9-foot wingspan. It takes off and lands vertically using four upward-oriented rotors joined by two wings. To convert to wing-borne flight, it pitches its entire body forward until its rotors are resting horizontally. The aircraft can then fly like a biplane. “It is 50 percent more efficient for it to fly wing-borne,” said John Wittmaak, program manager of small-medium UAS (unmanned aircraft systems) development at Bell Flight.

The APTs are not aimed at last-mile delivery directly to customers’ homes or workplaces. Instead, for urban applications, “we are focused on hub-to-hub or hub-to-kiosk flights,” Wittmaak said. “We see it often combining several packages in a single payload.” Delivery services can then bring packages to customers, or customers can visit kiosks for pickup.

Bell Textron had previously tested a smaller drone, the APT 20, which was designed for payloads of 20 pounds. The unit is looking to scale its drones to payloads of 500 pounds or so. “Whatever our customer requirements are, we will adjust to those requirements,” Wittmaak said.

Because its sensors do not rely solely on vision, the APT 70 can fly in the rain and in other low-visibility weather. “It is capable of fully autonomous landings in 20 mile-per-hour winds, and we think that can go up to 35 miles per hour,” Wittmaak said. “One day we will include flight into known icy conditions.”

Bell Textron is currently working on detect-and-avoid and landing zone evaluation systems for the APT 70, among other things, Wittmaak said. The company also is collaborating with Japanese logistics company Yamato Holdings on package-handling systems. “We are working on the ability to autonomously detach payloads,” Wittmaak said. “We are also working on more simplistic solutions where human operators unload payloads.”

The APT 70 achieved its first autonomous flight last August, with it following a preprogrammed flight path, and its first beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) flight in January. “With a loss of data link or communications, it can go to a predefined location and land itself,” Wittmaak said.

Bell Textron is aiming for its cargo drones to enter service in the mid-2020s. “It’s a race to see whether it will enter into service on the commercial or military side first,” Wittmaak said.

FUTURE FREIGHT

Although Elroy Air had briefly considered flying passengers when it started, “we quickly realized that as a startup, for us to quickly scale to operations and revenue in the next couple of years, flying cargo was the way to go,” Elroy Air’s Merrill said.

“The cost to certificate an aircraft to carry people is upward of $100 million, if not more,” Sabrewing’s De Reyes added. “In comparison, the cost to certificate carrying cargo only, no humans, is only about $40 million, which is much easier to raise, much more palatable for investors.”

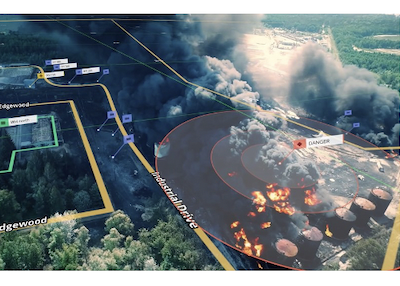

Although the path forward for cargo drones might be easier than that for those carrying passengers, it remains challenging. Aside from many regulatory hurdles, a key factor those developing cargo drones need to focus on is their infrastructure.

“Considerations have to be paid to things such as energy and maintenance,” said Parimal “PK” Kopardekar, director of NASA’s Aeronautics Research Institute in Mountain View, California. “The critical thing is scalability. For example, these aircraft will need periodic maintenance of some kind, like a car, so it will need access to parts and quick access to technicians, because nobody wants to wait around for an aircraft sitting on the ground doing nothing. All that needs to be designed to be situated at a local level.”

That “local level” will include hard-to-supply remote locations as well as urban settings. Sabrewing, for example, has a joint venture with the Aleut community of St. Paul Island in Alaska to order 65 aircraft and test its designs at the 126,000-square-mile St. Paul Experimental Test Range, which is centered in the Bering Sea. Lighter population densities also offers less risk of injuring people, Kopardekar noted.

“We are shifting to calling this field ‘advanced air mobility’ to be more inclusive of the emerging possibilities,” Kopardekar continued. He envisioned cargo drone supply chains connecting farms to restaurants or food banks in cities. Instead of trucks congesting traffic, cargo drones “could deliver materials from ports to as close as possible to their final destinations, significantly reducing times for transport,” he said.

Ultimately, success in the cargo industry field may come not from prime aerospace contractors but from ambitious startups. “Compared to the primes,” Merill said, “small companies and startups have a disruptive advantage because they can move so much faster, since they have very little to lose. A big company gets very risk averse because it costs them so much money to start a new initiative. There are 20 people who can say no in a big company, so things either get shot down or take longer.

“Speaking from firsthand experience, at a startup, once we have learned enough about a problem and what customers want, we can run full speed ahead, and we don’t have to worry about vendor lock-in or commitments to existing product lines. Once we get the first person to say yes to funding, it’s off to the races.”