The Deadly Drone Arms Race in Ukraine

The grinding war in Ukraine resembles warfare from bygone years in some respects,

but drones of many types are showing new ways of waging war.

Sixteen months in, the character of Russia’s foundered invasion of Ukraine has surprised analysts for the way it has come to resemble the muddy trench and artillery battles of World War I rather than fast-paced modern maneuver warfare. Furthermore, ground-based missiles have sharply reduced the effectiveness of air and sea power dramatically, reinforcing the predominance of old-school artillery and entrenched infantry.

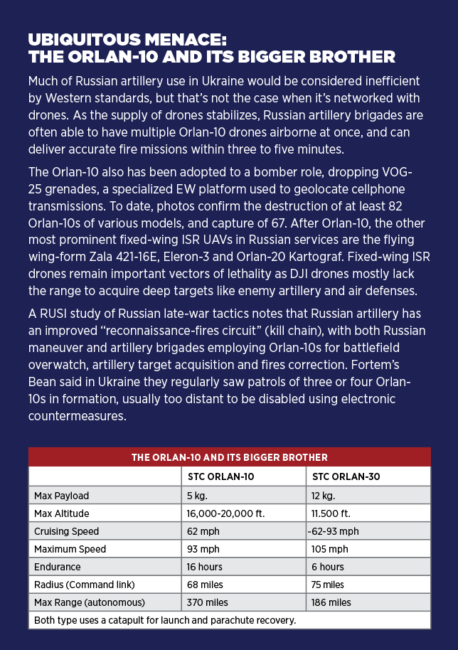

One of the more dynamic elements in the resulting grinding war of attrition has been the impact of unmanned systems, which in sheer volume are substituting for reconnaissance, close air support and even strike missions by manned aviation.

The impact is felt both at the tactical level by infantrymen and tank commanders benefitting from an eye in the sky, and on the strategic level, with both the Ukrainian and Russian capitals coming under attack by kamikaze UAVs (although Kyiv is suffering from that on a much greater scale.)

Moreover, importing or domestically building drones in a useful timeframe is much more feasible than other systems of military value, leading to a research and development and manufacturing race between Ukraine and Russia.

Since Inside Unmanned Systems’ first article on the role of drones in Ukraine’s war a year ago, some salient features have remained consistent, such as the huge role of civilian commercial quadcopters—with thousands donated by civilian donation drives—the frightening lethality of the drone/artillery team, and the importance of electronic warfare to support drone threats.

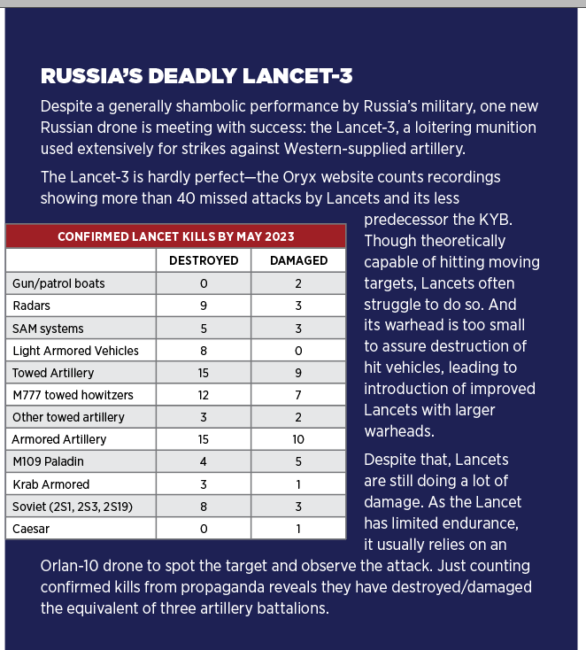

Other elements like large missile-armed unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) like the Bayraktar, have faded from public view, while new technologies have emerged in prominence, notably including first person view (FPV) drones and jet skis converted into long-range kamikaze craft.

RUSSIA’S STRATEGIC DRONE WAR

Late last summer, Russia began importing thousands of Shahed-136 kamikaze drones from Iran, along with similar but less capable Shahed-131 and a few Mohajer-6 UCAVs. That fall, Shahed-131s and -136s (designated Geran-1 and Geran-2 by Russia) entered action first against tactical targets in Kherson and Kharkiv, but then in massive assaults on Kyiv and other major Ukrainian cities in coordination with missile attacks to further strain air defenses.

The overall concept of these campaigns—largely not directed at targets of military value—recalled Hitler’s V-missile bombardment of London, aiming to wear away Ukrainian public support for the war effort through monotonous terror and fatigue, and compelling its targets to divert precious resources away from the frontline.

The Shahed, which cruises at around 75 miles per hour, isn’t hard to shoot down but it was so numerous and cheap at an estimated $30,000 apiece that Ukraine could not afford to expend its non-replenishable arsenal of Soviet air defense missiles on every one. Supposedly, Russia was setting up to begin license-building Shaheds in volume too, though the status of that project is unclear. That meant as many other alternative methods for downing them had to be explored as possible.

There are, fortunately, many kinds of less-expensive assets that can defeat an aircraft that moves slower than a World War I biplane fighter, but because of their shorter range, they must be distributed broadly to defend key target areas, and they require early warning so mobile assets can be pre-positioned and cued to the vector of their approach.

Those methods included radar-guided, self-propelled anti-aircraft guns, interceptor drones with nets, GNSS jamming and others.

In addition to radar, Ukraine has deployed an early-warning cellphone app allowing vetted observers to post reports of visual contact with drones and missiles—a high-tech version of the civilian Royal Observer Corps the United Kingdom relied on during the Battle of Britain to report movements of Nazi bombers overland after passing coastal early warning radars.

While Russia has also sought to adapt its Shahed tactics, Ukraine’s improving means and methods have increased the kill rate sometimes to 100%, or close to it. A massive strike on May 27 by 54 Shaheds saw 52 shot down, though the two downed “successfully” killed one civilian and injured another.

In theory, even ineffectual Shahed strikes might still contribute to Russia’s war effort by depleting valuable Ukrainian air defense munitions (the exhaustion of which would “unlock” Russian manned airpower), increasing the penetration rate of harder-hitting and more expensive Russian missiles, and generally stress Ukrainian defenses. But Ukrainian tactics and Western aid transfers have seen rapidly diminishing returns for Russia’s drone terror attack strategy.

Going forward, any credible air defense system near a hostile power must have a plan to deal with a high-volume threat like the Shahed drone without relying on powerful air defense missiles that may come with multimillion dollar price tags.

DRONE INTERCEPTORS

Given that drones like the Shahed cost way less than most ready solutions capable of defeating them, some have long argued the obvious solution is another (relatively) cheap drone. Already, footage of several “jousting” dogfights between commercial vertical-lift drones have been recorded over Ukraine, with usually one UAV managing to ram another until it crashes. But specialized UAVs could obviously counter enemy ones far more effectively.

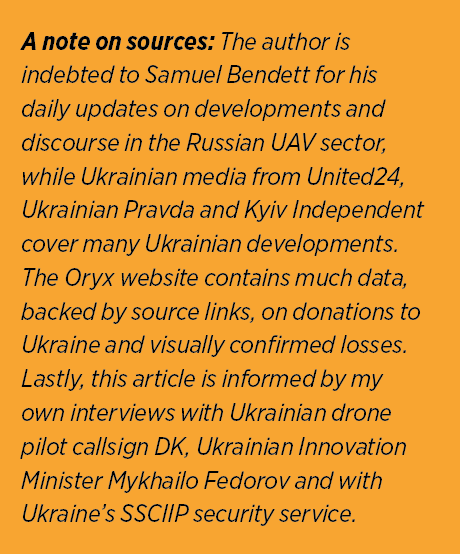

Indeed, such drone interceptors have been combat-tested in Ukraine today, including the F700 DroneHunter interceptor from Fortem Technologies.

Company Chief Operating Officer Tim Bean spoke with Inside Unmanned Systems just after returning from Ukraine, and made the case that relying entirely on electronic warfare methods to jam and hack drones was shortsighted as more serious operators, such as state militaries or well-funded terrorists, increasingly adopt autonomous drones with inertial navigation systems that can still perform without satellite navigation and command links. He also said GPS jamming and spoofing likely affect a drone shortly before it strikes its target, at which point a fast-moving drone is unlikely to change course much before impact.

At least six F700 UAS (also known as “Shahed Hunters”) are believed to have been deployed in Ukraine. Bean said these achieved a 90-100% success rate against group 1-3 drones, and complete most missions in two to three minutes.

Bean said the F700 had proven “very effective” against Orlan-10 and Shahed drones, though he couldn’t comment on whether they worked versus Lancet-3 loitering munitions, citing operational security concerns.

For now, Fortem is seeking to supply Ukraine with F700s both through direct sales, donations and via U.S. military aid. Looking ahead, Bean said counter UAS systems will increase in importance as much in the civilian as military domain. He believes a focus on long-distance sensors is myopic given that many smaller distributed sensors (“put ’em every 500 meters”) aggregated in a network are more effective in complex urban environments. Radars like the R20, currently priced in the $20,000 range, are highly scalable in price if ordered in sufficient volume using commercial, off-the-shelf components and could therefore become “the CCTV of the sky.”

OTHER ACTIVE INTERCEPTORS

The F700 is not the only drone-interceptor being combat-tested in Ukraine. Anduril has reportedly deployed the 12-pound Anvil drone interceptor, which can attain a speed of 100 miles per hour. These are deployed in launch boxes with two UAS each near points of interest.

MARSS’s NiDAR system can detect Class I and I UAS from 15 miles away, or mini-drones out to five miles. This may have included the company’s Interceptor UAS, noted for high maneuverability and maximum speed of 180 miles per hour thanks to its four ducted fans. It can destroy multiple small drones three miles out from its launch point.

Ukrainians have engineered their own shorter-range Fowler interceptor, with a maximum range of a mile, and which targets drones traveling up to 111 miles per hour at up to 3,300 feet. This 3.3-pound hybrid quadcopter-horizontal flight vehicle can be reused by attacking targets with a net, or operated as an expendable munition. The intended target set includes civilian Mavic-style drones and larger Eleron-3 systems.

George Dubynskyi, the deputy minister of digital transformation for Ukraine, said the need for counter-drone systems is “live or die. After Russia, in October of last year, started to attack our critical infrastructure, civilian infrastructure, and we were suffering from blackouts during the winter…any person in Ukraine will tell you we need these counter-UAS systems for that.”

He said Ukrainian officials believe they are “kind of a new European Israel, from the point of view of technologies,” for testing new systems and supporting companies that want to develop them.

“We welcome companies…we are ready to provide them with all necessary services to develop new tactical technologies in Ukraine because we need it right now and we believe that we will need them for decades, and that’s why we want to establish some powerful industry in Ukraine.”

UKRAINE’S STRATEGIC DRONE CAMPAIGN

Ukrainian attacks on Russian soil and occupied Crimea date from early in the war, typically involving low-flying manned aircraft, ballistic missiles and converted Soviet reconnaissance drones. But such long-distance drone attacks, using more replaceable UAVs of varying origin, have picked up sharply in frequency since the winter.

Notable incidents among many include: On May 30, between 16 and 36 Ukrainian long-range drones swarmed down upon Moscow between 5 and 6 a.m. Five were allegedly downed by Pantsir-S systems and three landed off target due to spoofing. The rest caused minor damage to residential buildings without loss of life. Some were carrying 4-pound KZ-6 shaped charge warheads.

Numerous attacks began last August on Russian bases and infrastructure in Crimea, destroying some aircraft on the ground and blasting the Black Sea Fleet’s headquarters with a Mugin-5 Pro drone; a Dec. 5 strike by converted Soviet target drones hit Diaghelivo (100 miles southeast of Moscow) that seriously damaged a Tu-22M3 supersonic bomber and killed a pilot and two technicians; in February, drones used by Belarussian opposition reportedly damaged the radar dish on a valuable A-50 Mainstay AWACS plane while landed in Belarus; on May 3, an attack with likely symbolic intentions by kamikaze drones in Moscow detonated directly above the spire of Putin’s Kremlin residence, the Senate Palace, while he was elsewhere.

These attention-grabbing strikes differ greatly from Russia’s drone attack strategy. They are low-volume precision strikes relying more on stealth than overwhelming numbers to avoid Russia’s powerful air defenses, and have caused few civilian casualties. It is likely that some of the attacking drones are launched by agents infiltrated into Russian soil. Others involve long-distance drones based in Ukraine relying on their low radar cross sections and low-altitude flying to evade detection. Some may still depend on infiltrated observers for terminal guidance.

RISE (AND DIVE) OF THE FPV DRONE

FPV drones, piloted using goggles projecting high-resolution wireless video feed from the drone itself, grew in popularity among drone hobbyists in the early 2010s, particularly for drone racing. They were improvised into kamikaze weapons early in the war, but their use was sporadic and a Russian source denigrated them as requiring too much skill to be practical for donation to frontline forces.

But in the winter of 2022-2023, Ukraine’s special operations branch demonstrated they had been sharpening their skills considerably when they began executing mass attacks by FPV drones. During a failed Russian offensive targeting Avdiivka begun that December, Ukraine’s Omega unit (ordinarily a counter-terrorism force) managed to knock out four Russian BMP fighting vehicles in a massed attack by FPV drones armed with conical RPG-7 warheads.

Since then, the frequency of footage showing FPV drone kills has risen considerably, and Russian drone operators believe they need to adopt them at scale too. Reportedly, Russian buyers were dismayed to find that Ukrainian agents had bought out much of the available international inventory of hobby FPV drones. Once again, DJI’s FPV racing drone is a popular base product, though Opterra’s E-flite and design by Rotor Riot have seen combat use too. American drone maker Red Cat Holdings Inc. recently said it will provide 200 long-range, high-speed FPV drones to Ukrainian pilots under a new purchase order from an unnamed source.

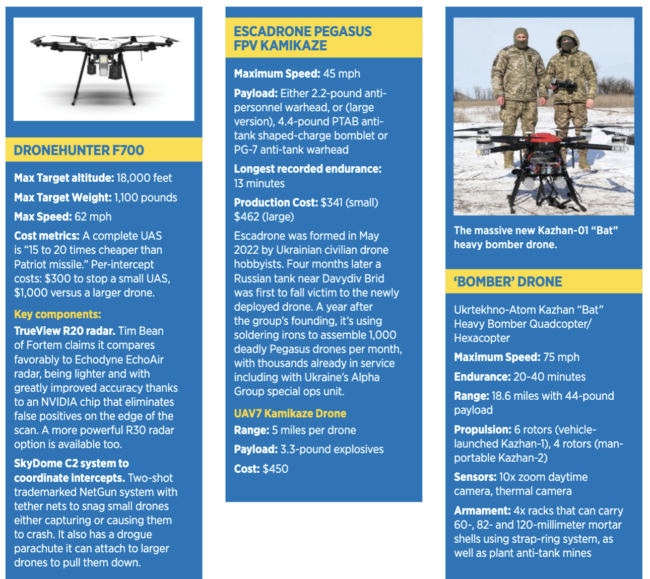

It has also become evident that Ukrainian companies are starting to build intentionally weaponized FPV drones on a huge scale, and that they are seen as an important offensive weapon. A Russian-aligned iniative in Zaporizhya is seeking to churn out hundreds of FPV drones per month as well.

Of course, an FPV drone is effectively a flavor of loitering munition like a Switchblade or Israeli Harops drone. They are faster than quadcopters (100 miles per hour or more) and thus more likely to evade defensive fire. They differ in their interface too, which is useful for targeting moving vehicles or indoor targets. However, Ukrainian and Russian commentators agree they require a much greater level of skill and training to effectively operate than a Switchblade or Mavic.

The author would postulate the large-scale adoption of FPV drones is a matter of cost and supply, with new, purpose-built FPV drones being built by Ukraine for just $250-400 apiece per various sources, while the most expensive parts of these drones—the goggles and controllers—are of course reusable. (Russian DIY-built FPVs appear pricier at about $1,250 for suggested components.) Thus, the resource intensiveness of FPV-operator training is seen as an acceptable price to generate volume in contrast to more expensive but far easier to use purpose-built loitering munitions. However, a Russian article notes that ineffective attacks by FPV drones are usually due to “human factors” and advocates further automation as the solution.

THE DJI WARS

On the battlefield, cheap civilian quadcopters continue to play major roles both as vital short-range reconnaissance/surveillance assets, and secondarily, as attack platforms usually dropping small grenades, or more rarely mortar shells.

Despite some Western drone donations, those built by Chinese company DJI continue to predominate due to lower cost despite a ban by Beijing on sales to Ukraine or Russia. Generally, field units prefer larger quadcopter or hexacopter drones with thermal cameras like the DJI Matrice.

Russian sources evaluating alternatives found there were none, judging the affordable Xiaomi 2 to have limited range, a weak camera and unreliable battery life indicators, the Autel EVO to be too vulnerable to electronic warfare, and the 3V-Copter Falcon unstable in heavier wind conditions and lacking a strong enough zoom.

Attacks with DJI drones can be seen picking off individual soldiers, and sometimes are effective even against main battle tanks with a number of videos showing drones dropping grenades (fitted with 3D-printed fins for accuracy) being dropped through a static armored vehicle’s open hatch, leading to combustion of its ammunition. This leads to drones also being frequently used to destroy immobilized vehicles that aren’t recoverable due to overwatching enemy forces. Russian propagandists have lamented on social media a “flock of [quadcopter drones] will break any Russian offensives. It’s painful to watch.”

Mavic drones have also been used very closely in cooperation with tanks on both sides, providing a vantage to spot entrenched enemy troops. Both sides now view overwatching drones as essential for spotting and providing command-and-control for armor operations.

C-UAS: 10,000 DEAD DRONES A MONTH?

Recently, Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) analyst Jack Watling reported that due to improved C-UAS tactics and technology, Ukraine is losing 10,000 drones per month. Subsequently on social media, he clarified he could not verify the figure but was told that by a Ukrainian official.

Interestingly, a Ukrainian drone pilot with callsign DK told me he believed drone losses had declined since last summer (when Watling reported the typical drone lasted only eight days of frontline use) due to operators implementing best practices and technical solutions to avoid losses to electronic warfare.

Watling’s report again highlights the effectiveness of Russia’s truck-based Shipovnik-Aero system, but also discusses how increased use of GPS-jamming and spoofing is degrading effectiveness both to drones and satellite-guided weapons. Ukrainian Minister Fedorov likewise emphasized electronic warfare as the most useful C-UAS system, and a priority for local R&D.

What seems clear is the electronic warfare environment, combined with deployment of C-UAS guns down to tactical units, results in a likelihood of loss for civilian drones that have not been hardened versus electronic attacks. According to the pilot, purpose-designed military unmanned system must be able to autonomously complete their mission or return to safe harbor upon loss of the control signal to reduce the effectiveness of jamming.

UKRAINE’S ASTOUNDING DRONE INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX

Through its United-24 fundraising platform, Ukraine has martialed an unprecedented global fundraising apparatus soliciting non-governmental donations that will directly go to equipping frontline units with drones. Ukraine’s innovation minister Mykhailo Fedorov told me in an interview early in May that it had procured 3,857 UAVs with a value of $113 million through financial donations or mailed-in physical “dronations.” Stunningly, he indicated those amounted to “equal numbers” with drones purchased by Ukraine’s defense ministry (though likely those included more expensive UAS).

Meanwhile, as the mass production of FPV drones reveals, Kyiv has been fostering development and production of many new types of UAVs from diverse manufacturers, including a project to develop an indigenous DJI substitute.

The director of Ukraine’s Security Service claimed the number of indigenous companies developing or building new UAVs had tripled from 30 pre-war to 90, each, he claims, building as many as five different varieties. Kyiv overall is devoting 40 billion UAH (roughly $1 billion) to drones in 2023; a modest sum by the standards of the Pentagon that goes a very long way in Ukraine.

When I asked Ukraine’s SSCIIP security service which Ukrainian-built drones were of greatest importance, a source cited several new drone designs I was unfamiliar with from my knowledge of Ukraine’s drone inventory at the onset of hostilities, including the Carboline Mara-2, Cetus minidrones and the Kazhan drone bomber.

Ukraine also has been custom-assembling increasing numbers of larger six or eight-rotor “bomber drones” capable of dropping multiple heavy munitions as large as 120-millimeter mortar shells.

Kyiv’s success is only possible thanks to a parallel program to train thousands of drone pilots, which began before the war. Since then, Ukraine’s Army of Drones program reported that by May it had trained 10,000 new drone operators. Furthermore, there’s a culture welcoming inputs from civilian volunteer organizations such as Aerorozvidka, which eventually became part of Ukraine’s military and built the Predator R18 drones, Ukraine’s OG drone bombers.

With all this activity, Ukraine’s drone industry could be positioned to prosper post-war in both civilian and military domains.