Counter-UAS systems are combatting a vertical security gap when it comes to smuggling contraband into prisons.

Prisons are designed to keep inmates inside. But over the past decade, an array of nefarious drones has added a dimensional threat—the airspace above correctional facilities. Increasingly, quicker, high-flying, longer-range, payload-enhanced drones can commit illegal acts from a distance.

Aerial assaults have featured a cornucopia of contraband:

• Drugs dropped into an Ohio facility sparked fighting in the yard.

• Contraband delivered over a Maryland prison was collected by an inmate dog-walker.

• Dropped drugs were hidden inside a pigeon in California.

• A handgun was flown into a high-security prison in Canada.

• More than $1 million in contraband was delivered over numerous flights in the United Kingdom, with inmates grabbing deliveries from their cell windows.

“Drones pose a serious threat to the safety and security of the BOP’s institutions, inmates and staff,” announced the conclusions and recommendations section of the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ 2020 threat report.

“It’s stunning,” said Mary-Lou Smulders, chief marketing officer and head of government affairs for global airspace security company Dedrone, describing “the new asymmetric threat.

“Forget that cake with the knife in it. Since the beginning of time, people have been trying to secure their fortress. But you can’t build a wall high enough to protect you from something that can simply fly over you.”

A MULTILAYERED STRATEGY

Current federal and state laws severely limit the use of drones to mitigate other drones. Consequently, today’s full C-UAS correctional facility program needs a comprehensive sequence involving legal means to detect, react to and legally counter threats from above. The protection sequence can involve a threat assessment; an “airspace audit” to diagnose exposure; real-time detection to identify drone type; capabilities integrated into existing protection; and an alert system to buy time as authorities trace the flight path to locate and deter the pilot. Lessons learned can then harden future security.

All this requires a considered approach to deterrence, said Casey Flanagan, president and co-founder of AeroVigilance, a counter-drone consulting and training company based in the greater Richmond, Virginia, area. “The process is to discuss with our customer where their problem is, what they are seeing, if they have any detection technologies already, but also to implement a multilayer strategy,” he said.

As with so many things, nothing’s perfect. “No one drone detection technology is a panacea; they all have strengths and limitations,” wrote RTI research forensic scientist Neal Parsons in the June 2023 report “Addressing Contraband in Prisons and Jails as the Threat of Drone Deliveries Grows,” published by the National Institute of Justice.

Parsons, who also leads the Criminal Justice Technology and Evaluation Consortium’s counter unmanned aircraft systems research, testing and evaluation effort, endorses a multilayered approach to “overcome the performance gaps of an individual technology.

“Producing a very thorough counter-UAS system,” he told Inside Unmanned Systems, “has to employ multiple different sensors to overcome gaps in performance. Radar covers a wide area, but you don’t want your team to be notified when anything is flying in the air.

“The next layer would be to interpret what that actual notification is. An EO/IR [electro-optical/infrared] camera can hone in on that drone and the operator can identify competently that a drone is inbound. If you want to go to the third or fourth layer,” Parsons said, “then you’re adding additional modalities like RF solutions.”

Flanagan, who served on the FBI’s counter-UAS team, addressed another set of requirements. “If you don’t build the supporting policies, procedures, response tactics, staff training and personnel, then the technologies can only do so much,” he said. To that end, AeroVigilance operates the C-UAS Hub as a portal for the security information community.

Dedrone’s Smulders noted yet another elephant in the correctional C-UAS room—budgets. “I would even argue that our largest competition is simply not having the line item.”

“Public safety is already doing more with less,” Flanagan added. He suggested crunch-easing tactics: “How else can your equipment be used? Can you enable drone first responder operations? Some special events support? Get more mileage.”

APPLICATIONS

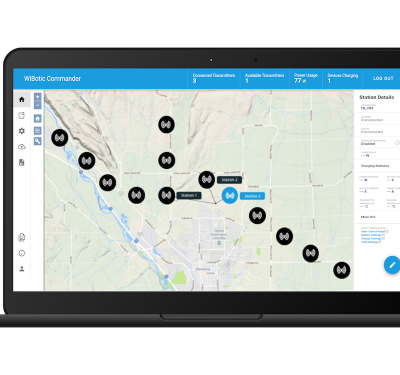

Dedrone’s DedroneTracker.ai detects, identifies and locates unauthorized drone threats, automatically sending alerts to security teams. Connecting to DedroneSensors and allied technology allows for tracking a flight path.

“Security gets better as you add more layers,” Smulders said. “We take the input from the camera, lots of AI imaging software supplied from the RF sensor radar and we decide two very simple questions: ‘Is it a drone?’ ‘Where is the drone?’ That applies an additional level of behavior modeling to give you a more accurate picture of where exactly the drone has been, where it is right now, even a small prediction of where it will be in the future.” A heat map can identify favorite launch locations and facility hideaways, especially in older prisons rife with nooks and crannies.

“You can see the data and understand what’s going on in your airspace, how you need to respond.”

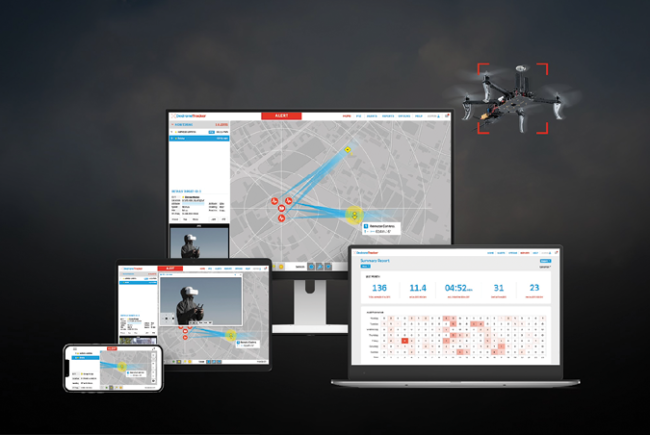

DroneShield is an Australian-U.S. company that operates primarily in the defense space but is tapping into correctional needs with sequential fixed, mobile and body-worn solutions. RFAI, a passive detection capability embedded on all DroneShield sensor products, can detect and classify UAS via communications signals to pilot controllers. “With our C2 software, you can draw areas of interest and set those up for multiple alerts, with fewer false alarms than radar and the ability to hold track when drones hover,” U.S. CEO Matt McCrann said.

DroneOptID and its AI-powered optical detection, ID and tracking system also record camera footage to use as evidence, while DroneSentry C2 is a graphical interface that “merges all sourced detection data onto one screen, with mapping and zoom capabilities.”

Though the FCC currently precludes use of RF-disruption systems beyond the U.S. government or its representatives, DroneShield’s roster of fixed, mobile and handheld disruption products like DroneGun Mk4 and the rifle-style DroneGun Tactical can be used by select federal law enforcement in cooperation with correctional staff. “With customers that have the authority to mitigate or defeat, you can send the drone home or drop it right there,” McCrann said. (Dedrone and Israel’s Phantom Technologies are also among those developing drone guns.)

“A layered approach and multiple options,” McCrann concluded.

NEXT STEPS

Deploying detection systems at scale is becoming cost-effective, especially across larger states. Operator training is expanding. Federal and state legislation continues to evolve, if slowly.

AeroVigilance’s Flanagan seeks balanced growth. “My hope is that the authorities take a ‘whole of government’ approach so we can enable drone operations for the betterment of society but also protect it from the nefarious use of drones. That would include expanding detection authority down to the SLTT [state, local, tribal and territorial] level,” he said.

Dedrone’s Smulders reiterated her protect-all-dimensions perspective. “If you had a big hole in your wall at the prison, you’d go, ‘Wow, that’s kind of a problem.’ I think it will be generally understood that not having an airspace security solution is like having a big hole.”