As the war continues into its third year, how is the domestic drone industry in both countries supporting their war effort, and who currently has the upper hand?

Both Russia and Ukraine have cadres of highly motivated and educated civilians who, outside the bounds of the defense industry, have rapidly developed, hand-assembled and delivered to military units in volume deadly UAS that have transformed the battlefield.

Russian volunteer groups struggle to receive support from Russia’s federal government, which prefers dealing with large, politically influential defense conglomerates. Ukraine’s Ministry of Digital Transformation and its energetic minister Mykhailo Fedorov, on the other hand, have created an R&D and procurement apparatus with heavy use of crowdfunding separate from Ukraine’s traditional defense-industrial complex.

The ministry’s approach, for good or ill, has been to support a wider range of solutions rather than to focus on a small number of champions—an approach evident in its procurement of UGVs.

In February, President Zelensky also inaugurated a new military branch—the Unmanned Systems Forces, dedicated to all classes of unmanned systems. The inauguration on the Unmanned Systems Forces increases, but also simply reflects, the political clout unmanned systems have acquired in Ukraine due to their prominent military successes. This service was formally stood up in June starting with 3,000 personnel and commanded by a Colonel.

A typical R&D cycle can see new drones devised over a few months’ time and rapidly transited to combat tests in the field with specific Ukrainian brigades rather than being facilitated through national-level agencies. The ensuing product demo videos don’t involve 3D animations, but actual combat footage in kinetic environments.

Beyond the businesses and non-profits, Ukraine’s “People’s FPV Program” reportedly recruited thousands of civilians for manual assembly of FPV drones, which can be done at a table at home with only a soldering iron and screwdriver. One Ukrainian professor described to Forbes building 21 FPV drones over two months in his spare time using parts purchased through online fundraising. One would expect significant quality control issues, though allegedly 80% of drones built via the program pass inspection.

Through various channels, Ukraine by early 2024 had reportedly doubled sUAS production to 100,000 systems monthly, which should suffice to attain the goal stated by President Zelensky to procure a million drones in 2024.

Ukraine’s diversified non-profit and small business UAV builders still face many challenges and have developed their own ecosystem of supporting system builders specialized in drone controllers and munitions production. For example, Steel Hornets, which has styled itself as the Amazon of drone-sized munitions, delivered anti-tank and personnel bombs with everything but explosive fillers.

At the same time, Ukraine continues energetic purchases of Chinese civilian drones and drone parts through middlemen despite a Chinese ban on drone exports to Ukraine or Russia. In late 2023, Ukraine’s prime minister claimed Kyiv had purchased 60% of DJI drones ever produced.

NIGHT TERRORS: UKRAINE’S BABA YAGA HEAVY BOMBER DRONES

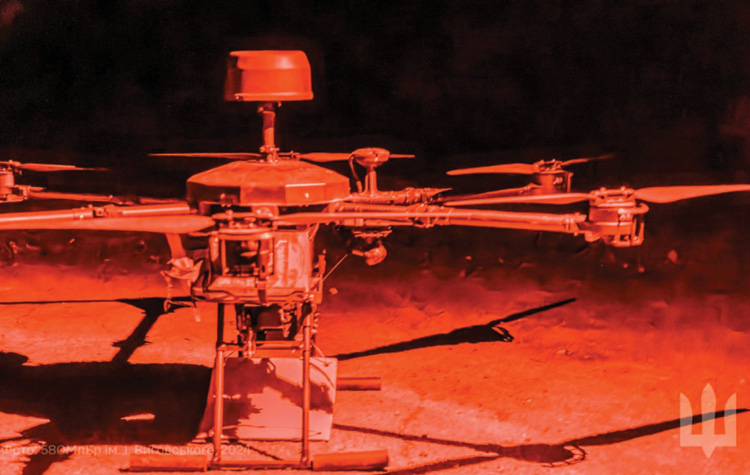

A uniquely Ukrainian drone warfare capability comes from its fleet of heavy bomber drones collectively referred to as “Baba Yagas,” which bring destructive force at night like the eponymous forest witches in Slavic folklore. The heavy bombers are noisy and easily spotted, hence their nighttime deployments always with thermal cameras.

The original Baba Yaga was the indigenously built R-18 octocopter, but these have been complemented by popular DJI Matrice 300s, Kazhan 620 Bats and the smaller Vampyr hexacopter. A crashed Baba Yaga inspected by Russian soldiers had a Starlink satellite uplink, a Raspberry Pi computer but also a surprising quantity of indigenous Ukrainian components like two-way radios and video transmitters.

Their gravity-dropped payloads can range from a half-dozen mortar bombs to TM-62 anti-tank mines rigged with contact fuses—weapons that can blast through defenses effective against FPV drones. Broadly, they achieve 60% accuracy at an altitude of 260 feet. Furthermore, a Baba Yaga downed in August mounted a curious 5” diameter BK-30F weapon, perhaps including components of the Soviet Kobra tank-launched missiles or Ukraine’s Korsar ATGM.

Baba Yaga night attacks “inflict heavy damage to our soldiers and fortified areas,” one Russian soldier writes on social media. Russian sources also alleged Ukraine has developed an acoustic-stealth Baba Yaga.

The bombers have proven difficult to down with jamming, though it’s not strictly impossible. However, Russian posts online reveal two more successful counter-tactics: interception by more agile FPV drones, and shootdown by snipers equipped with infrared goggles using aimed single-shots. Ukrainian operators in turn deploy smaller quadcopter FPVs to escort the valuable Baba Yagas. These escorts intercept Russian FPVs attacking the Baba Yaga and attack ground-based air defense systems that open fire, providing additional surveillance and target acquisition.

One Chechen officer claimed online that Baba Yagas were used to carry away wounded soldiers at night. They cannot, but Baba Yagas have employed grabbing systems to snatch equipment such as encrypted radios, assault rifles, crashed FPV quadcopters and even, once, a grounded Orlan-10 fixed-wing drone. Initially, Ukraine’s 128th Brigade devised a triple-hook system built from used grenade rings, but now they employ 3D-printed grabbing claws.

RUSSIAN DRONES AND “JUDGMENT DAY”

Russian FPV manufacturing likely exceeds Ukrainian output at this time—and is supported by diverse volunteer efforts across Russia. A turning point came in the Fall of 2023 when Russia’s Defense Ministry decided it was time to finally pour state resources into FPV production. It essentially took over and scaled up the privately funded Sudoplatov Group, choosing to mass-produce its VT40 drone for its “Judgment Day” program.

By December 2023, Sudoplatov claimed it was hand-assembling more than a thousand VT40s daily, and footage of warehouses with buzzing 3D-printers and stacks of hundreds upon hundreds of FPV drones supported the assertion.

The crushing scale of the Russian FPV mass-production machine is deadly—but it’s reportedly much less deadly than it could be due to inferior technical quality, organizational dysfunction and less

sophisticated tactics per accounts of Russian drone operators on social media.

“An operator who launches 30-40 drones a day and has zero hits is a very typical story,” one operator lamented. David Hambling wrote at Forbes that Ukrainian operators report hitting targets 20-50% of the time. Russian operators appear less successful in staying ahead of Ukraine’s electronic warfare (EW) capabilities, and often wastefully expend individual drones against EW “walls” until one finds a gap through dumb luck.

But a Russian source also said electronic friendly fire is inflicting up to 50% of losses of Russian drones due to often non-existent communications with neighboring units outside their chain-of-command vertical. One Russian wrote on social media, “The lack of a sane communication and control system at the platoon-company level creates the impossibility of guaranteeing the safe flight of your reconnaissance quadcopter form the rear to the front line and further to the enemy.”

It seems the shortcomings of Russia’s centralized FPV production compared to Ukraine’s “thousand flowers blooming” model has made its way to senior leadership. By fall, Russia’s new defense minister Belousov—and later Putin himself—indicated they wanted to pivot toward supporting more diverse UAV production efforts. Dubbed the “People’s Defense Industry Complex,” including a new tech accelerator called RIVIR. Russian media published and then retracted a quote by Belousov claiming 4,000 FPV drones were being built daily, i.e., 1.4 million annually.

VT-40: MANUFACTURING SUCCESS, BATTLEFIELD MEDIOCRITY?

Sudoplatov’s VT-40 FPV kamikaze has decent performance on paper: a maximum range of 4.3 to 6.6 miles, and payload of 7 pounds, typically an RPG warhead. Ostensibly it’s built with 90% indigenous components. And there’s no shortage of footage of their effective use.

But by spring, Russian volunteer drone-makers had grown bitterly critical of Sudoplatov, arguing that Russia’s defense ministry was devoting all its resources to an inferior product. Though these were hardly unbiased critics, accounts by Russian operators tend to support their assertions. One Russian instructor of Storm-Z assault troops writes, “Assembly quality [is] so poor with [the] least expensive components possible, one-third on average simply won’t take off, requiring resoldering of defects.”

Such critics also claim Ukraine has tailored their jamming efforts specifically to disable VT-40s, which failed to evolve in response. The same instructor wrote, “They reach the target only if [jamming-free] windows appear. A common practice is to hit a target with only one drone from a series of several units, the rest simply fall.”

GHOUL AND EXTENDER

Beyond Sudoplatov’s output, Samuel Bendett, an analyst at CNAS told IUS, “Russian soldiers are using Ghoul (Upyr), Ovod, Piranha, Horetnisya, Joker, Gastello, Molniya fixed wing and many other [drones] that don’t get a lot of news or Telegram coverage. Some of these are supplied only to specific units and formations, others are more widespread across the force.”

An allegedly “good” FPV drone cited by critics of the VT40 is the Ghoul, which completed combat tests in April 2023. Two Ghoul operators were credited by Russian media with the destruction of an Abrams tank at Berdychi, near Avdiivka, in February with hits to the top and side turret.

Designed by an engineer in Yekaterinburg, Ghoul is produced from molded and pressurized thermoplastic, fiberglass beams and 3D-printed parts at a unit price of $552. Distinguished by its prominent antennas, it attains a 66 mph attack speed and can deliver its 4.4 pound warhead out to 7.5 miles, though its control links is limited to 3-5 miles.

Ghoul’s full range is achievable using a repeater relay drone known as Udlintel (“Extender”) that increases control range by 6-10 miles. An Extender accidentally shot down by Russian troops who displayed it on social media revealed a mix of customized plastic parts and foreign components such as an Express LRS video/transmitter system.

LANCET: FLAWED YET EFFECTIVE?

Lancet (detailed in IUS Oct/Nov 2023) is one of Russia’s rare technological success stories, including kills of Leopard 2 and Abrams main battle tanks and landing MiG-29 jet fighters and numerous Western-supplied artillery systems. Gen. Valeriiy Zaluzhnii highlighted in an article that Russia used Lancets “quite effectively” in a counter-battery role.

Yet Russian and Ukrainians accounts make clear that Lancet has major flaws—achieving kills with direct hits isn’t guaranteed. One Ukrainian PzH-2000 armored howitzer reportedly survived three hits. Towed gun crews often overhear Lancets and escape before being hit.

In 2024, Russian operators typically post 140-180 Lancet video per month, save for a surge of 302 recorded strikes in May. Pro-Russian website Lost Armor enthusiastically collects statistics on these videos—and their figures are not particularly self-congratulatory.

Out of 2,365 videos posted by September 8, they confirmed kills in 666 of them (28%), damage in 1,223 (51.7%), clear misses in 7.4% and found 13.2% undeterminable. These are only the videos that operators chose to post online. Attacks on moving targets are very rare, just 5.3% of total. Yet, Lancet’s medium-range capability set and scale of production make it a deadly weapon against valuable targets despite its high failure rate.

Lancets are often sold for far above their cost-to-produce. Due to high demand, the now-sanctioned Vostok Design Bureau has developed a lower-capability Scalpel drone costing one-tenth the price, roughly $3,300, to complement Lancet. This drone nonetheless looks capable on paper with a 25 mile range and 12 lb. payload. Its builders have worked on improving catapult launch systems and ISR capability but were not yet able to integrate automatic target lock-on as originally hoped.

AMERICAN DRONES SUPPLIED TO UKRAINE: A DISAPPOINTMENT?

Donated Western drones have received less and less coverage over time as Ukraine’s indigenous UAVs are produced in numbers overtaking donations in importance—and in many cases, capability.

Skydio Executive Adam Bry told The Wall Street Journal that his UAVs “were not a very successful platform on the frontlines” and that “the general reputation for every class of U.S. drone in Ukraine is that they don’t work as well as other systems.” WSJ characterized U.S. drones as “expensive, glitchy and hard to repair.”

Lack of hardening against EW is clearly an issue. Furthermore, manufacturers particularly blame the U.S. regulatory environment and Pentagon procurement culture, which bans rapid software upgrades made without military approval. A ban on affordable Chinese components used ubiquitously by Russians and Ukrainians also makes drone development much more expensive, which some builders argue hurts more than helps the U.S. drone industry.

U.S. UAS are indeed very expensive compared to Ukraine’s. But are all U.S. drones performing equally poorly? For example, an operator of Switchblade-300 munitions told Ukrainian media that while their small warheads aren’t optimal for the conflict, they serve a useful niche role targeting high-value personnel and equipment because of their ability to precisely fly through building windows. Further afield, Ukrainian drone operators also appear fond of medium-level ISR drones built in Poland and Germany and have adapted Australian drones for long-distance strike missions.

SECRET IDENTITY REVEALED: ATLAS, DOMINATOR AND PHOENIX GHOST

The U.S. has likely transferred well over 2,000 Phoenix Ghost loitering munitions produced by Aevex Aerospace to Ukraine. Early Congressional reports total 1,801 drones given, but subsequent transfers did not specify quantity. Reportedly they’ve proven successful, with Ukrainian presidential adviser Oleksii Arestovysch stating they achieved a 60% hit rate. These were born of the Pentagon’s innovative Big Safari program, but their appearance remained a secret. That has likely changed.

In April, California-based Aevex announced at an Army Aviation expo in San Diego that more than 4,000 of its Atlas and Dominator drones had been delivered to Ukraine where they were “combat proven” and the “No. 1 U.S.-government provided loitering munition to Ukraine.” These loitering missions with pusher piston engine propulsion feature autonomous navigation and recognition technology and can be reconfigured for ISR and EW missions. They were designed on open-architecture principles to enable easy introduction of third-party software and payloads and reportedly conduct autonomous operations aided by sensor fusion, using computer vision to autonomously identify landmarks and navigate relative to them without GPS, or per company literature, “navigate, make decisions and complete missions without direct intervention.”

According to Aevex, it is building 300 drones per month for Ukraine, and thousands more are on order. A new facility opened in October 2023 boosted total monthly capacity to 450 aircraft on 1.5 shifts, or 1,000 with three shifts.

Resembling a bowling pin with swept wings and an upward canted V-tail, Atlas’s described missions sets include ISR, detect, identify, locate and report (DLIR), Electronic Warfare, and “precision attack.” It has long range for a Group II drone.

The typically gas-powered Dominator instead has a twin-boom tail configuration and boxier hull. It can be launched and recovered from a short runway or catapult.

NATIONAL UAS PROGRAMS AS THE WAR PROGRESSES

Ultimately, small business and volunteer groups have played a critical role for both Russia and Ukraine in designing and producing UAS that now have an overwhelming impact on the battlefield. Ukraine, however, has seemingly done a better job in maximizing output by its “popular” drone sector by creating parallel, national-level structures dedicated to shepherding innovation into testing and production, exterior to the established defense procurement bureaucracy in government-to-corporate contracting. This has allowed Ukraine to repeatedly innovate, and scale deployment of new designs faster than Russia has—though the innovation advantage is always temporary due to Russia’s ability to observe and replicate methods used against it.