As the U.S. seeks to contain China, the U.S. Navy is betting big on unmanned systems with some significant budget requests.

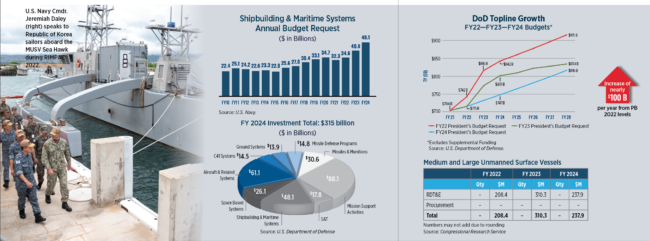

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) recently released its budget request seeking $842 billion for fiscal year 2024. For its part, the U.S. Navy has asked the DOD to allocate 15%, or $48.1 billion, of the DOD’s $315.0 billion total investment budget toward shipbuilding and maritime systems.

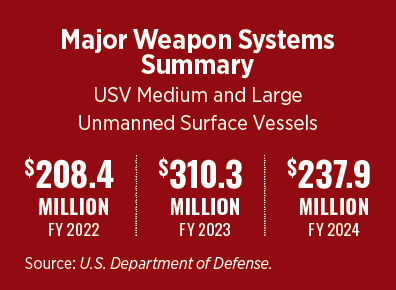

Add to this the seafaring service’s ask for a combined $555 million in research and development funds for large unmanned surface vehicles (LUSVs), medium unmanned surface vehicles (MUSVs), LUSV and MUSV enabling capabilities, extra-large unmanned undersea vehicles (XLUUVs) and core technologies for unmanned underwater vehicles. These big dollars merit a dive into how these maritime unmanned vehicles fit into the larger defense and Navy strategies.

DEEP SEA-TED RIVALRIES

Last Fall, the DOD unleashed the unclassified version of its National Defense Strategy, or NDS. It outlined the main focus of defense efforts as “the need to sustain and strengthen U.S. deterrence against China.”

The strategy frames the challenge presented by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a “coercive and increasingly aggressive endeavor to refashion the Indo-Pacific region and the international system to suit its interests and authoritarian preferences.” This, the NDS says, is both a pacing challenge and the single “most comprehensive and serious challenge to U.S. national security” today.

China’s destabilizing activities along the Line of Actual Control, a notional line of demarcation between China and India, as well as across the East and South China Sea rank high on the list of concerns swirling around the country. According to the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations, China continues to claim sovereignty over the sea, along with its estimated 11 billion barrels of untapped oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. Among other actions it has taken, China has physically increased the size of islands or created new islands by piling sand onto existing reefs to bolster its claims. China has constructed 27 outposts in the form of ports, military installations, airstrips and even deployed fighter jets, cruise missiles, and a radar system across the Paracel, Spratly and Woody Islands.

This grey zone remains red hot. The Associated Press reported just two months ago that China threatened “serious consequences” after the U.S. Navy sailed its USS Milius guided-missile destroyer near the Paracel Islands.

THE STRATEGIES HAVE FLOWED

And so, to tackle these PRC challenges, as well as others including threats posed by Russia, North Korea, Iran and violent extremist organizations, the NDS outlines four top-level defense priorities. They include:

- Defending the homeland, paced to the growing multi-domain threat posed by China

- Deterring strategic attacks against the United States, allies and partners

- Deterring aggression while being prepared to prevail in conflict, when necessary; prioritizing the challenge posed by China in the Indo-Pacific region and the Russia challenge in Europe

- Building a resilient joint force and defense ecosystem.

The three ways the department intends to advance those priorities include integrated deterrence, campaigning and building an enduring advantage across all theaters, across the full spectrum of conflict and all domains.

The 2023 National Defense Science and Technology (S&T) Strategy, titled “Sharpening Our Competitive Edge,” molded itself around these priorities. It posited “accelerated technology advancement and innovation” as key elements to achieve them. The S&T Strategy outlined three main lines of effort.

The first was a focus on the joint mission: establish systems and processes to make cross-service threat-informed S&T investment choices because “any future fight will be a joint fight.”

Next was create and field capabilities at speed and scale: foster the defense innovation ecosystem to accelerate the transition of new technology into the field.

The third was ensure the foundations for R&D: focus on talent, infrastructure (physical and digital) and stakeholder collaboration in direct support of national security.

That said, even before these high-level strategies flowed, the Navy had been thinking about these same goals, including how a healthy mix of unmanned systems could contribute to its overall joint capabilities. Two years ago, it revealed the Unmanned Campaign Framework, a first-of-its-kind pronouncement to “make unmanned systems a trusted and sustainable part of the Naval force structure…in support of the future maritime mission.” Its goal: to forge human-machine shipmates to enable distributed maritime operations (DMO) for the Navy. DMO is all about using dispersed forces to deny freedom of movement along key sea and air lines of communication. Unmanned systems are a key component of this approach.

And now, in support of the NDS, S&T Strategy and its prescient Unmanned Campaign, the Navy has asked Congress to invest in the uncrewed tools to help secure the nation.

THE WAVETOPS ON USV AND UUVS

Besides the Navy’s request for the third largest slice of the DOD’s investment pie chart ($48.1 billion) for shipbuilding and maritime systems, it also has asked for millions more in support of uncrewed systems R&D. Specifically, the Navy seeks $117.4 million for LUSV programs, $85.8 million toward MUSV programs, $176.3 million for LUSV/MUSV enabling capabilities, $104.3 million in XLUUVs plus $71.2 million for UUV core technologies.

So, what are these vehicles and why are they important, in the context of current strategies? A Congressional Research Report on the Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles reveals the Navy hopes to use these vehicles to launch a distributed fleet architecture. Diversifying with these assets will help move the service further away from traditional approaches that focused on just a few high-dollar ships. And so, the Navy seeks to procure low-cost, high-endurance, reconfigurable unmanned surface vehicles.

One type of such vehicle, the LUSV, is a semi-autonomous or optionally crewed ship. They run about 200 feet to 300 feet long and weigh about 1,000 tons to 2,000 tons when fully loaded. Building on the DOD’s Strategic Capabilities Office Overlord LUSV prototype effort, the Navy envisions these reconfigurable ships will carry multiple modular vertical launch systems, or launch tubes, for anti-ship and land-attack strike payloads. Designed to have operators in-the-loop or on-the-loop, these systems will include autonomous navigation, transit planning and COLREGS-compliant maneuvering, as well as automated propulsion, electrical generation and support systems.

In early 2022, the DOD transferred the four LUSVs created as part of the Overlord project to the Navy’s Surface Warfare Development Squadron. Ever since, the Navy has been using these prototypes to develop deployable concepts of operations.

Now the fiscal 2024 budget projects LUSVs to be procured as follows: one in FY 25 at $315.0 million; two more in FY 26 for a total of $522.5 million; three additional in FY 27 for $722.7 million and another three in FY 28 for a total $737.2 million.

The smaller MUSVs will measure approximately 45 feet to 190 feet in length and weigh in at about 500 tons, similar to current patrol craft.

The Navy originally awarded L3 Harris the $35 million MUSV contract in July 2020 for the MUSV prototype with delivery of the initial prototype in the fourth quarter of FY 24 and the option to purchase eight more in the future. Currently, no funding exists for MUSVs funded in the FY 24-FY 28 Future Years Defense Program. The Navy is asking for those funds to be secured now.

To complement these innovative uncrewed surface ships, the Navy seeks funding for its subsurface uncrewed vehicles, or XLUUV, as part of its Orca program. A bit too large to be launched from a crewed submarine at 84 inches in diameter, the idea is to launch these submarine-like vessels from a pier.

The Navy already has five of the XLUUVs, previously funded in FY 19 through its R&D line. It selected Boeing for its prototype, which it dubbed the Echo Voyager. Boeing’s product sheet indicates the Echo Voyager is roughly the size of a subway car. At 51 feet in length, its rectangular cross section measures 8.5 by 8.5 feet. It weighs 50 tons (out of water) and can roam up to 6,500 nautical miles, even with a 34- to 85-foot payload.

The Navy now seeks another XLUUV in FY 26 for $113.3 million; another in FY 27 at $115.6 million and a third in FY 28 for $117.9 million.

WILL THE FUNDING TIDE ROLL IN?

The Navy’s budget justification for these systems explains their criticality to securing the maritime environment and anticipated return on investment. It states, “LUSV is a key enabler of the Navy’s DMO concept, which includes being able to forward deploy and team with individual manned combatants or augment battle groups.

“In that DMO context, LUSV will complement the Navy’s manned combatant force by delivering increased readiness, capability and needed capacity at lower procurement and sustainment costs and reduced risk to sailors.” LUSV, the justification continued, will be capable of weeks-long deployments and trans-oceanic transits and operate aggregated with Carrier Strike Groups, Amphibious Ready Groups, Surface Action Groups, and individual crewed combatants.

The smaller MUSVs will also play a key role in the Navy’s DMO concept. Instead of surface warfare payloads like the LUSV, the Navy will use MUSAVs for battlespace awareness. They will carry intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance and electronic warfare payloads and deploy for weeks-long trans-oceanic transits either alone or alongside Carrier Strike Groups and Surface Action Groups.

For DMO, ASW capabilities supplied by the XLUUV remain strategically important to protect joint forces against the lethality of submarines in the joint fight.

Clearly, the success of distributed maritime ops will rely on Congress’ distribution of funds for these uncrewed maritime assets. Only time will tell if those with the power of the purse believe in the power of uncrewed sea power.