Editor’s Note: Christian Ramsey, uAvionix Chief Commercial Officer, provides context on existing technological safeguards that can help prevent aircraft collisions like the one near Washington, DC on Jan 29. A regional jet and Army Black Hawk helicopter collided close to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA).

“I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” – The Psychology of Science: A Renaissance, Abraham Maslow (1966)

At uAvionix, we try to walk a line between advocating for what we think is the right solution and appearing too commercially motivated. We strive to be trusted, to be the responsible aviation stakeholder voice with experiences as pilots, as ATC, as enthusiasts, as advocates for the next era in aviation, and having foundations in National Aviation System (NAS) modernization. In the tech industry, it’s a common refrain that someone has the hammer that is going to nail down the world’s problems – if only the world would listen. We really try not to be “that guy.”

But this time, forget that. We just lost 67 people in a midair collision that I feel I’ve spent the last 15 years of my life building a hammer to prevent. My family can tell you that I took it personally and it has made me angry, sad, and motivated to be more outspoken.

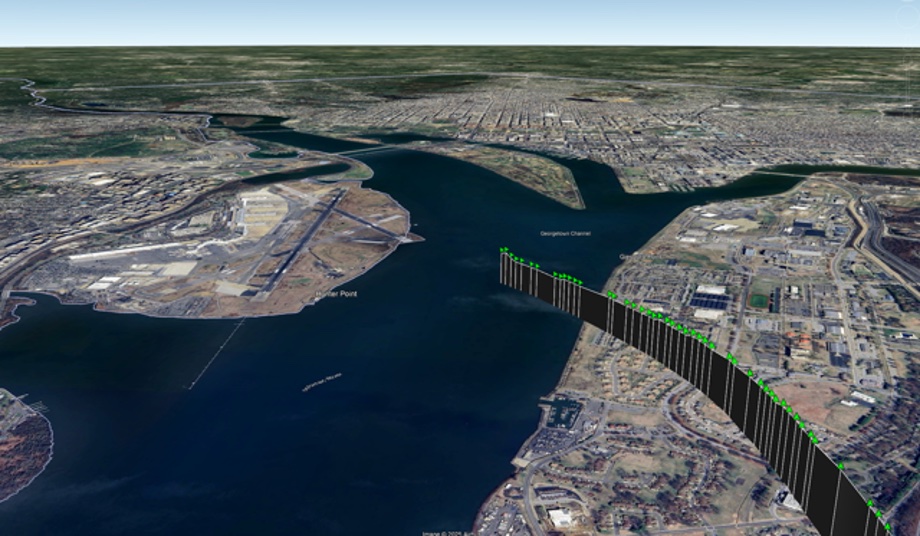

Within minutes of the first news reports about the collision, members of our uAvionix team produced the image below showing the flight path and last moments of AAL 5342. We pulled this from data from a private ADS-B receiver we had previously installed about a mile from the collision point. The most obvious thing? No flight path of the helicopter was present, meaning it either didn’t have its ADS-B system turned on, or didn’t have one at all.

Nearly a week later, this was confirmed publicly by the FAA. The installed system was turned off, and Senate Commerce Committee Chair Ted Cruz rightly railed that “there was no compelling national security reason for ADS-B to be turned off.”

It would be a bit audacious for me to say that had the helicopter had ADS-B enabled the crash would have been averted – there is no way to know that. But we know the aviation safety system is made up of “layers of safety” constructed in a way that if one layer fails another is there as a backup. In this case, one layer of safety was present but removed.

ADS-B works two ways – there is a transmitter on the aircraft (in the industry called “ADS-B Out”) and a receiver that can exist anywhere really, on an aircraft, on the ground, on a drone – the receiver is called “ADS-B In”. The signal is intentionally not encrypted to maximize safety and encourage everyone to use it. A study published in 2019 shows that the combination of ADS-B Out and ADS-B In can reduce the probability of a fatal midair accident by 89%, yes that’s 89%!

Much has been published about what the pilots of each aircraft could ‘see’…with their eyeballs. Does it not seem absurd that we are relying on the naked human eye at this point in time in both the busiest and safest airspace in the world? It certainly does to me.

In the US, ADS-B Out is legally mandated in controlled airspace – since 2020, which accounts for the airspace above 18,000 feet and around our busiest airports including DCA. But that leaves a lot of geographic airspace where it is not required. There are also a few exemptions, including military aircraft and aircraft that do not have electrical systems like gliders, balloons, and some vintage aircraft. ADS-B In is not mandated at all, but this turned out to be good because not having a mandate enables commercially available receivers priced as low as $200 to be used with iPads in the cockpit.

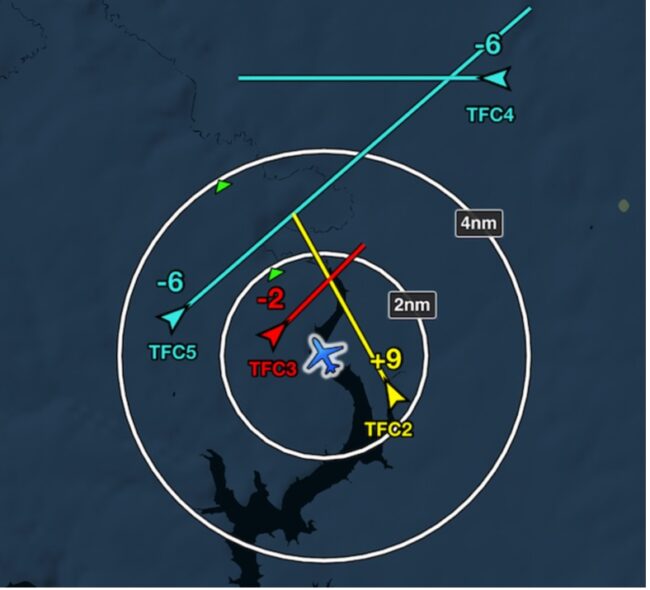

If one of these were in use in the helicopter, I honestly do feel strongly that the accident could have been averted. Take a look at the image below of one of our receivers, the Sentry, and the iPad image it generates. This clearly distills the operational picture down to the information that the pilot needs to know. Ownship, meaning the plane where the receiver is installed, is represented by the blue aircraft and other aircraft in the vicinity are clearly shown with relative altitude and range.

Despite the improvements in safety these mandates have achieved, the patchwork of airspace and specific aircraft exemptions has created safety gaps. The FAA publishes ADS-B equipage levels on their website, and as of Jan 1, 2025 – nearly 170,000 aircraft have ADS-B Out installed. What they don’t tell you is how many aircraft are NOT equipped – frankly, because it’s not entirely clear how many aircraft there actually are – but the general consensus is that it may be around 200,000 aircraft, leaving 30,000 unequipped aircraft out there.

Why aren’t they equipped? It comes down to two things – cost and privacy. There have, to date, been some pretty successful industry lobby groups fighting what we call “universal equipage” on those grounds.

It costs a minimum of a couple thousand dollars to equip a general aviation aircraft with ADS-B Out. Here’s what I have to say about that – it’s cheaper than a funeral. Even so, uAvionix has pioneered portable ADS-B systems in other countries that are not legal in the U.S. that cost about $750. So let’s take those 30,000 aircraft and say an average of $1750 per aircraft to equip with either installed or portable ADS-B Out, and you end up with a price tag of about $50M. That’s a big number for sure, but the total cost of the DCA accident will likely fall in the several hundred million dollar range due to hull loss, investigations, operational disruptions, recovery efforts, lost lives, and the activities that will follow for years to come on what went wrong and how to move forward.

Privacy? We need to get over it. There are too many instances in our country of safety mandates overcoming privacy concerns in public safety, telecommunications, commercial vehicles, etc. and it is just time to get past it.

In the name of Government Efficiency

Finally, the Air Traffic Control (ATC) system and government efficiency has been topping the news cycles lately. Lots of discussion about the antiquated myriads of systems out there holding the National Airspace System (NAS) together.

The problem is that we are now stalled in achieving the full promise of ADS-B in the NAS because of these gaps and exceptions. We are essentially running NextGen technology and OldGen technology simultaneously, and the lack of universal ADS-B Out equipage introduces additional costs and inefficiencies that ripple through the NAS. Here’s a short list to name a few:

- Ongoing radar maintenance and infrastructure costs – because not all aircraft broadcast ADS-B, the FAA cannot fully retire or downsize traditional infrastructure, resulting in high maintenance costs, inefficient duplication of surveillance, and slower modernization.

- Inconsistent surveillance data and ATC workload – due to different systems in place in different locations – some controllers receive lower fidelity updates for aircraft, creating blind spots and increased workload to conduct position checks.

- Inability to fully optimize separation minima – one of ADS-B’s major benefits is the potential to reduce separation minima in airspace where all aircraft broadcast reliable data. However, if even a few planes lack ADS-B, controllers must maintain larger separation minimums for the entire stream or revert to radar-based standards, preventing the NAS from achieving peak throughput. This also results in higher fuel-burn and arrival delay instances for the aircraft involved.

- Slower integration of new entrants into the airspace – millions are spent by the Uncrewed Aircraft System (UAS) industry trying to develop and qualify effective technologies to detect aircraft not equipped with ADS-B (known as non-cooperative aircraft). If all aircraft were equipped, a simple ADS-B receiver could suffice.

We’ve got a hammer, and while we can’t fix everything, we surely can make a meaningful improvement in safety using technology that exists today at a cost per aircraft that can be counted in hundreds or single-digit-thousands of dollars each. ALL of that cost will be recovered, and more, in efficiencies gained by a homogenous, streamlined NAS.