Russia’s fleet of Tu-22M Backfire, Tu-95 Bear and Tu-160 Blackjack strategic bombers can launch nuclear-armed cruise missiles capable of annihilating a city or military base. And over the last three years, they have launched thousands of conventional cruise missiles that have brought terror and destruction to cities in Ukraine.

But on June 1st, the buzz of tiny motors heralded the onslaught dozens of small FPV kamikaze swooping down on Russia’s bomber fleet with havoc on the agenda. On the ground, the dated but powerful Cold War dinosaurs are vulnerable to the smallest and cheapest of precision weapons.

Ukraine’s SBU intelligence agency shared videofeeds showing the drones swooping over bombers and crashing into them, with several aircraft visibly destroyed, damaged or on fire in the background. Russian civilians posted videos showing plumes of black smoke rising from the bases.

Almost 5000km from Ukraine, a Ukrainian drone operator takes his time in choosing the perfect point of impact to destroy this Tu-95 strategic bomber that regularly rains missiles on the cities of Ukraine. pic.twitter.com/CqDcHqY35I

— Kyiv Insider (@KyivInsider) June 1, 2025

Ukrainian drones struck Russian strategic aviation at the Belaya air base in Irkutsk – 4,800 km from Kyiv. pic.twitter.com/UBAi7znioR

— Michael MacKay (@mhmck) June 1, 2025

Russia’s military announced fives bases had been attacked, claiming Dyagilevo, Ivanovo and Ukrainka airbases escaped damage, while admitting aircraft casualties at Olenya airbase in Murmansk and Belaya airbase in Irkutsk, respectively 1,150 and a staggering 2,700 miles away from Ukraine.

Video showing drone launched from truck. https://t.co/mf8ErnLKNf pic.twitter.com/0MbXD7fKo6

— Def Mon (@DefMon3) June 1, 2025

Meanwhile, the SBU claimed its Operation Spiderweb struck 41 strategic aircraft (presumably either damaged or destroyed), with President Zelensky subsequently claiming 34% of the cruise-missile carrying bombers landed at the targeted bases were hit.

Covert drone infiltration

Operation Spiderweb was not, say, simply an unusually successful long-range strategic drone raid of the kind launched continuously since 2023. Rather, it was a covert operation executed by small short-range drones (reportedly built exclusively from indigenous or Chinese parts) infiltrated deep into Russian territory. Though Moscow claims to have detained Ukrainian perpetrators, Kyiv says all its personnel were already safely returned to Ukrainian territory.

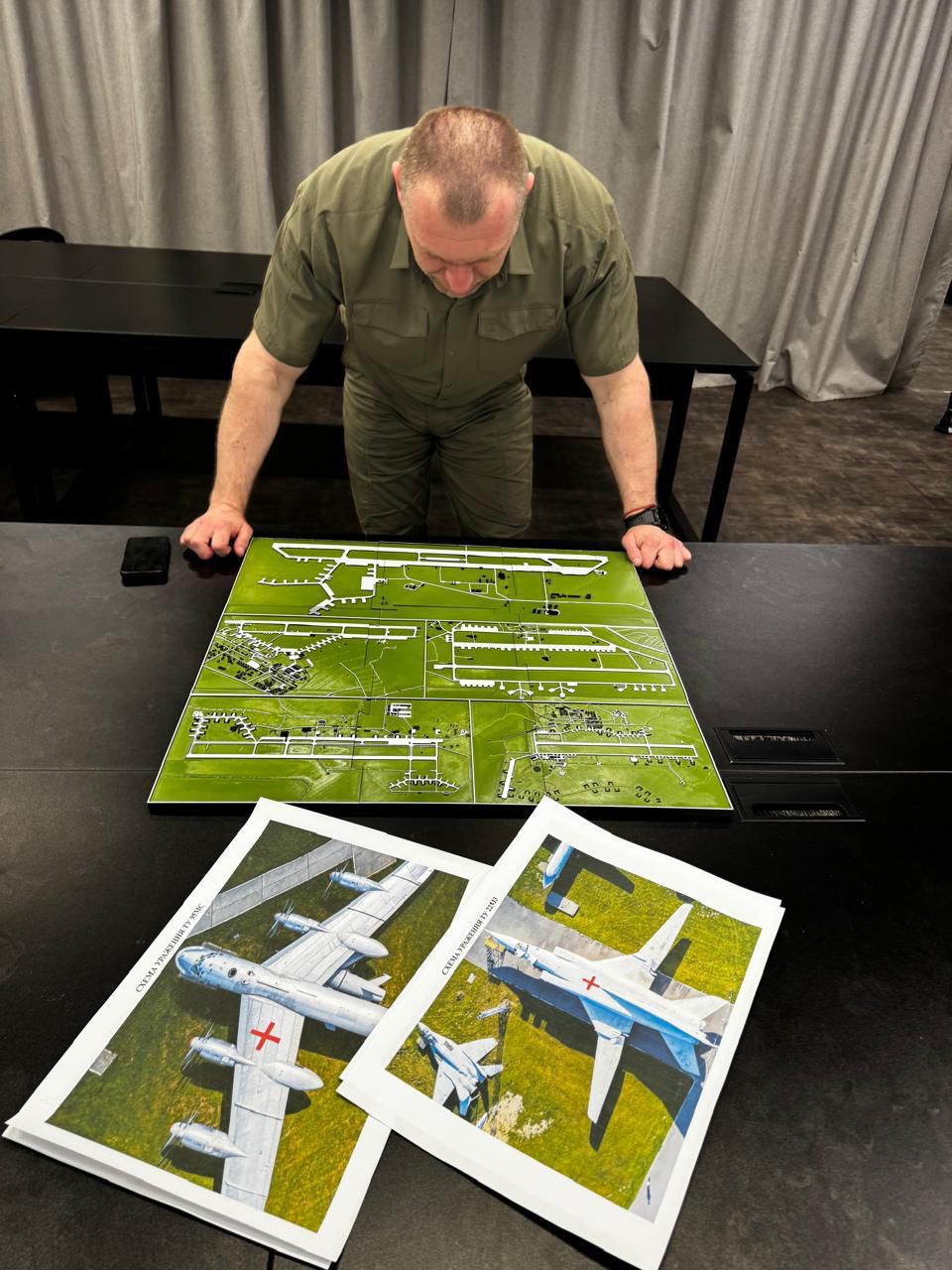

On social media, President Zelensky claimed planning for Operation Spiderweb began over 18 months earlier (ie. December 2023). To get short-range drones into strike range, the SBU first separately snuck 117 FPV drones and transportable wooden sheds separately into Russia (likely through Kazakhstan). Then in a rented Russian warehouse, the drones were installed for concealment under the roofs of the sheds. These were then loaded onto semi-trucks and “delivered” by unwitting Russian drivers to locations near the five strategic bomber bases.

On D-Day, a signal caused the roofs to open, allowing the drones inside to takeoff and attack. Some Russian civilians witnessing the drone launches were recorded climbing on trucks attempting to stop the drones. Two of the drone-launch sheds were also recorded exploding, the one near Ukrainka reportedly before it could launch its attack.

Russia’s Fighter-Bomber Telegram channel noted the drones popped up within the minimum engagement range of Russia’s surface-to-air defenses.

How bad was the damage?

Militaries historically often overestimate their successes, so it’s worth determining how many aircraft losses can be confirmed using open-source means.

First, you can see a satellite photo taken of Belaya the day prior packed full with over 80 aircraft, including 42 strategic bombers. Meanwhile, four heavy bombers and three Su-34 jets were visible at Olenya.

Initial recordings shared by Ukraine show the destruction of an An-12 cargo plane and two Tu-95s bombers at Olenya, another Bear damaged, and a fourth visibly damaged and possibly destroyed by fire. Some early satellite photos taken after the raid show the carbonized remains of three more Bears and what appear to be at least three supersonic Backfires.

The revetted parking positions. pic.twitter.com/WNFYnlEZDz

— Chris Biggers (@CSBiggers) June 2, 2025

There remain unverified claims of strikes hitting a huge Tu-160 bomber and an A-50 radar plane at Ivanovo. More imagery will surely follow.

Even just the loss proven so far constitute substantial damage to the air-based component of Russia’s nuclear deterrence triad, particularly as Moscow currently lacks the ability to build replacements for its Cold War bomber fleet.

Russia began the war with 128 heavy bombers in service, and prior Ukraine attacks using various kinds of drones already confirmedly destroyed at least three Tu-22Ms and damaged two more bombers between 2022-2024, compelling the withdrawal of bombers from Engles airbase located closer to Ukraine. Age and operational use have reduced mission availability rates considerably, perhaps explaining a significant decline in cruise missiles launched at Ukraine in 2025.

Guidance from afar

Given the challenges of controlling small drones from over 2,000 miles away, it’s worth considering exactly how Ukraine directed the drones on their attack runs. SUAS are usually tethered to short-range command-links, an attack using SUAS might ordinarily involve drone operator(s) located near the target.

And the videofeeds suggest the SUAS were remotely piloted (or at least pilot-able), not just following pre-programmed instruction—though autonomous UAVs can send back videofeeds too.

Defense analyst Dmitri Alperovitch wrote that Ukraine used the Ardupilot open-source flight software to control aircraft using unencrypted 4G/LTE connections—taking advantage of the local civilian cellular network to execute the attack. Russia’s Shahed/Geran kamikaze drones are also known to have tapped into Ukrainian cellular networks. Telecommunication providers may eventually be required to develop countermeasures to rapidly identify and exclude actors 4G to conduct drone attacks.

Use of satellite uplinks also seems possible, though given significant costs, these might have been installed in a minority of infiltrated UAVs (or the sheds they were concealed in), with the uplink systems relaying commands and video feeds from the other drones.

Lastly, the extent that autonomy played a role is unclear. The SBU claim use of “AI” for navigation to airbases and to acquire strategic bomber targets. Operators or AI were also apparently trained specifically to detonate the drone’s shaped-charge warheads targeting wing-mounted missile pylons and their nearby fuel tanks.

The threat from infiltrated SUAS

Remotely piloted FPV drones already account for an estimated 70% of battlefield casualties in Ukraine. Clearly large numbers SUAS could eventually become even more destructive as software and miniaturized sensors evolve to enable autonomous cooperative swarming attacks.

But no matter how evolved, small, low-cost SUAS face significant “delivery” issues when it comes to threatening tempting targets beyond ground frontlines like large military bases or warships at sea. Such small systems intrinsically lack the range to reach them—ordinarily.

To circumvent range limitations, various projects are developing ways to release SUAS from missiles or mothership vehicles. However, infiltrated SUAS will remain a persistent threat wieldable by state and non-state actors alike.

Operation Spiderweb represents the most spectacular, but by no means the first large-scale SUAS attack on a military airbase. Ironically, Russia was first to experience one in January 2018 when infiltrated Syrian rebel SUAS assailed Khmeimim airbase in Syria, damaging warplanes and causing one KIA. And since 2022 its bombers have repeatedly come under various kinds of drone attacks from Ukraine.

The methods allegedly used to defeats attack on the three other Russian bases bear study. But clearly, Moscow failed to appreciate how it’s more distant bases were vulnerable to attack too.

Russia’s vulnerability, however, is mirrored in many U.S. bases, as well as those of allies. Given that effective FPV drones can mostly be manufactured through civilian parts, border controls cannot eliminate this threat. For that matter, civilian cargo ships could effectively conceal hundreds of SUAS in shipping containers. One can imagine schemes to unleash concealed, pre-positioned SUAS assets to conduct Pearl Harbor-like surprise attacks.

Without doubt, Operation Spiderweb will be studied widely by friend and foe alike, and various actors across the globe will seek to replicate its methods. To manage the threat posed by infiltrated SUAS, valuable assets must be systematically protected by C-UAS defenses, including both radar and optical detection systems, electronic-warfare defeat methods, kinetic kill and energy-weapon short-range air defenses, and interceptor drones. Layering multiple detection and kill solutions helps ensure flexible means to deal with varied threats, such as un-jammable autonomous or fiber-optic UASs.

Beyond that, Operation Spiderweb is yet another reminder of best practices in shielding expensive military aircraft from attack: protecting and concealing them inside hardened concrete shelters, and presenting multiple convincing decoy targets to divert enemy fire.

Russia has also tried placing tires on top of landed bombers hoping to confuse automatic target recognition systems, a countermeasure observable in the recordings of burning strategic bombers.