As more growers embrace precision agriculture and the operational benefits drones can offer, manufacturers are finding ways to more effectively integrate ground and aerial sensors, and to handle all the data increasingly popular advanced solutions are able to collect.

When John Rocconi started flying drones for his customers three-and-a-half years ago, his main goal was to identify fallen corn crops. As a seed provider who breeds corn hybrids, he needed to know which varieties exhibited standability issues during wind events. Deploying RGB cameras on drones, he found, was much more efficient and economical than hiring a pilot to fly manned aircraft over the fields.

Seeing the potential these systems held, he added his first sensor to the payload within a year—making it possible to collect even more data and to try more sophisticated use cases.

Today, Rocconi, who is a product manager and agronomist for Erwin Keith Inc./Progeny Ag Products of Wynne, Arizona, uses solutions from Sentera to monitor crop health and provide status updates for growers. Instead of relying on out-of-date, low-resolution satellite imagery or hiring someone to come in with expensive tools and hardware to analyze the fields, Rocconi flies a drone to quickly gather necessary data so growers can make informed decisions about their crops.

“We collect imagery and plant health data for them during the growing season hoping to save them money inputs,” he said. “Growers are most worried about if there’s a problem in their field. We identify an area or land mass or acreage that has a problem and then go out into the field and determine what happened. Before, we had to send out plant samples, hope to collect a representative sample of the field and then wait for the results to come back from the lab.”

Through these types of missions, unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) have become a critical part of precision agriculture, quickly providing growers, agronomists and companies that serve the industry with high-quality images and data while also offering them vital but previously inaccessible information. Growers are collecting data from ground sensors and using automation to speed up processes and make up for labor shortages, and they’re flying their fields with UAS to check on irrigation issues, locate pests and plant counts, to name a few applications. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and visual and machine learning also play a crucial role in precision ag, especially as the industry calls for more specialization and an easier way to digest data.

“In the next few years agriculture will be totally different. Agriculture will be data driven, which it’s not right now,” said Yiannis Ampatzidis, assistant professor in the Agricultural and Biological Engineering Department at the University of Florida Southwest Florida Research and Education Center, Immokalee. “Imagine all tractors being driven without people and robots doing all the work. With machine learning and AI, you can train the robots, both ground and aerial, to learn from the data to complete specific tasks, which of course helps with efficiency and cost. Automation and AI will change agriculture.”

DIGITAL FARMING, SMART TECHNOLOGY AND AI

There was a time, not that long ago, when growers only could collect the most basic information from their fields, Ampatzidis said. Digital farming makes it possible to obtain very specific data, such as where growers should spray pesticides or chemicals to battle insects and weeds, and where they shouldn’t. Ground sensors collect data about moisture, the weather and machine performance, and GPS enables them to track if they missed an area that should have been sprayed. Software then visualizes the collected data so there’s no need for users to pour through Excel files.

“I can see the soil moisture and decide I want to irrigate the field remotely from my office,” he said. “There are also fully automated systems where a computer will decide to irrigate a field. All these sensors generate a huge amount of data. Our goal is to understand this data and develop algorithms and techniques to help growers manage it.”

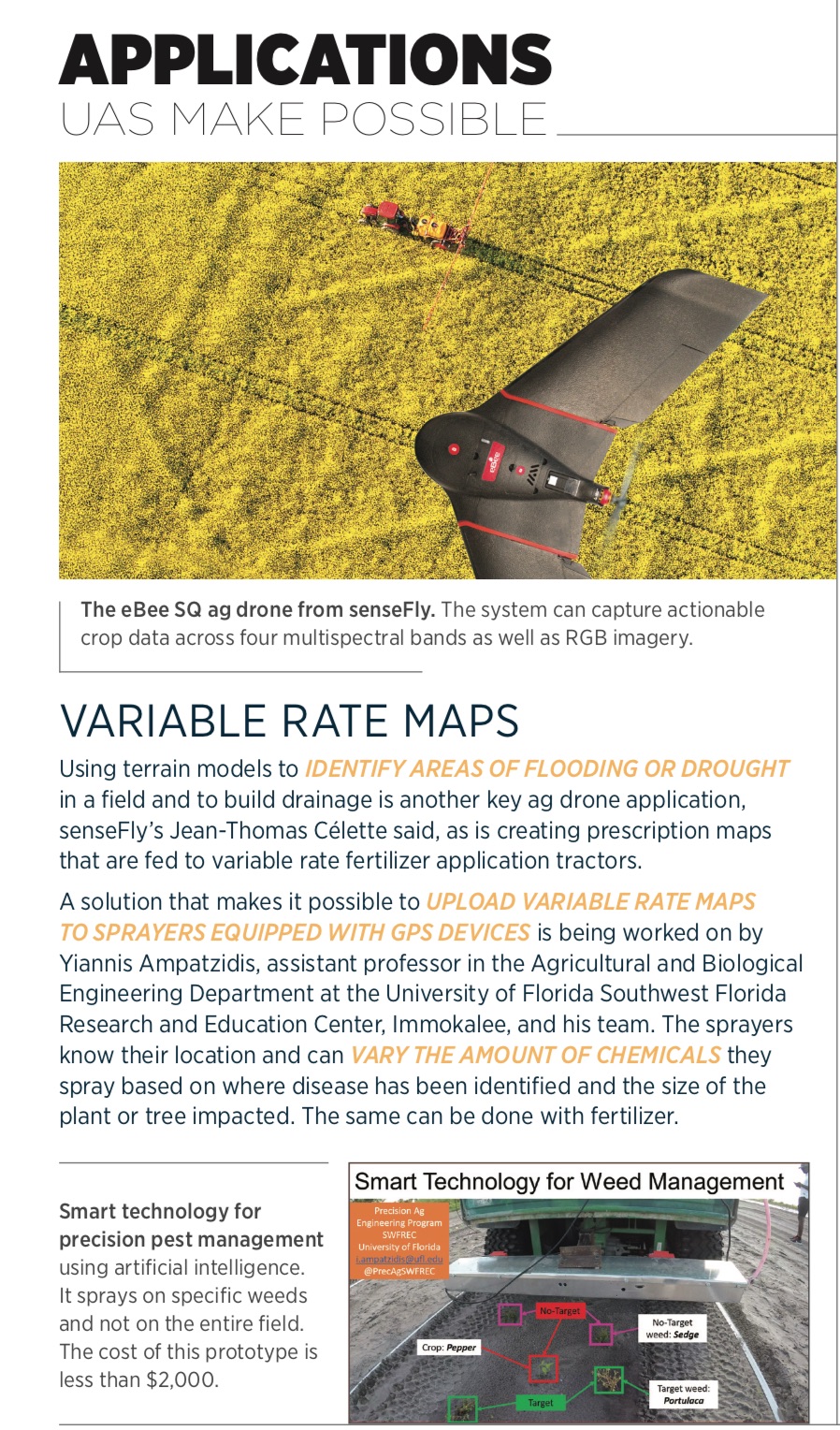

Smart technology, such as precision sprayers, also plays a huge role, Ampatzidis said. Once farmers know where pesticides are needed, they can program the sprayer to cover those areas rather than the entire field—increasing profits while also protecting the environment.

Ampatzidis and his team are working to develop such a system. The AI/vision-based solution distinguishes weeds from crops, and uses that information to spray only where needed. The system can identify three different types of weeds and spray the herbicide that kills those specific species.

The Florida group also is using AI to count citrus trees via drones. Some fields have as many as 10,000 trees of different sizes and ages, making it difficult for growers to keep track of them and to identify which ones may be effected by disease.

“We can count and detect trees and categorize them with more than 99.9 percent accuracy,” Ampatzidis said. “It’s a very practical tool for citrus growers as well as vegetable growers.”

Scouting technology also can create an index that indicates health status and stress for each tree. Multispectral and hyperspectral cameras can detect symptoms the human eye can’t see, allowing them to identify disease earlier. Workers no longer need to walk entire fields looking for problem areas, which is costly and time consuming.

Ampatzidis expects to see more AI-based machines and tools that complete specific jobs in the near future. For instance, one robot will fertilize while another sprays. Fleets of ground and aerial robots will be connected, allowing them to more effectively complete tasks.

DATA INTEGRATION AND COLLECTION

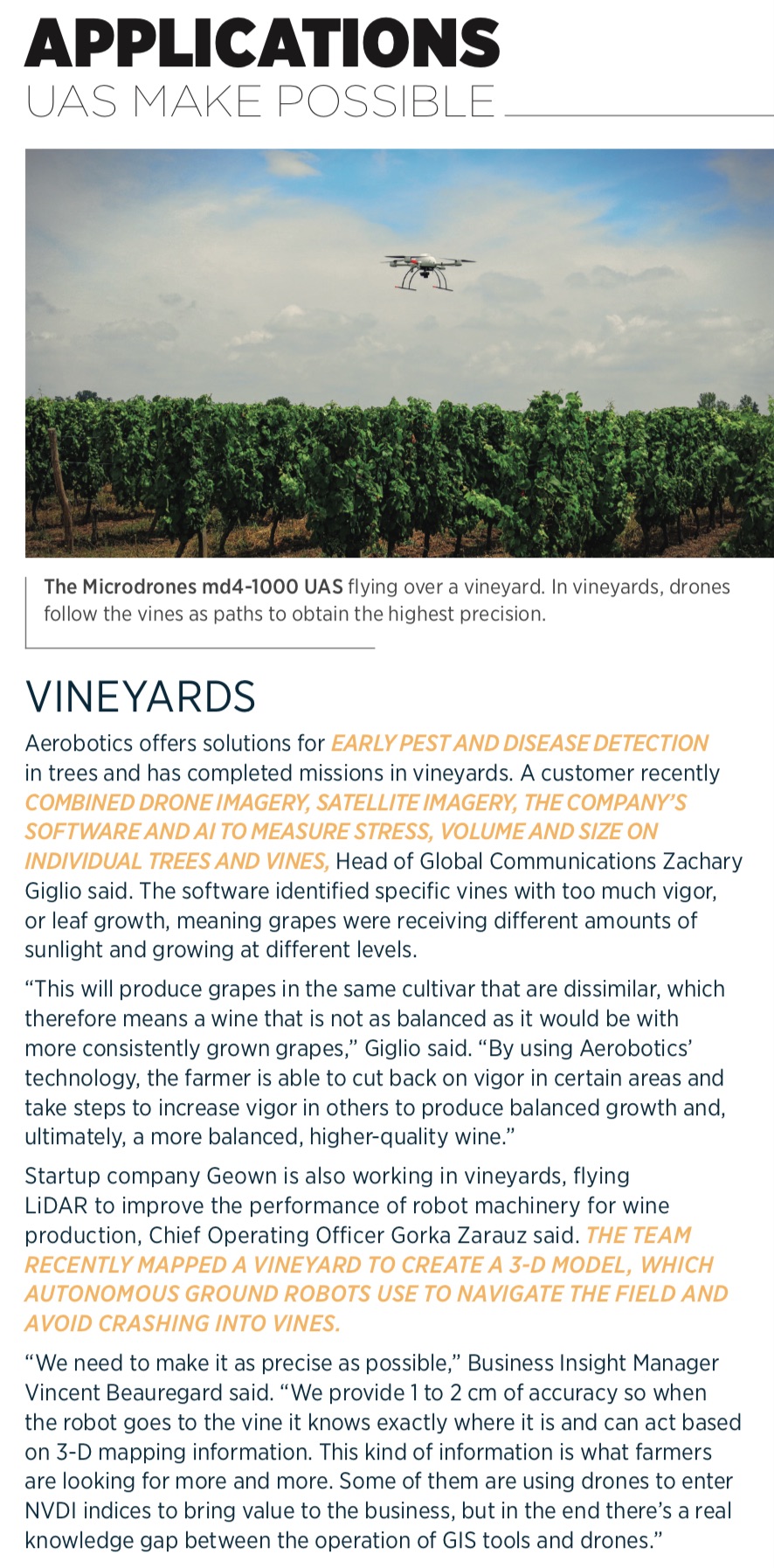

Integrating drone and satellite data as well as ground inputs is the next big step that will advance precision agriculture, said Kevin Lang, general manager of agriculture for PrecisionHawk Agriculture Services, of Raleigh, North Carolina. Combining weather data and analytics with drone data using satellite imagery as the base layer offers a more complete picture for effective crop-management decisions. Information also can be put into machine learning models, helping growers identify damage and disease. Everything will be customized.

That said, growers still need systems that ease data management and enable correlation between what’s measured and what they can do with it, said Jim Love, Light Robotics Manager for Beck’s Superior Hybrids, a retail seed company in Atlanta, Indiana. “The big trick is the data comes from all of these different machines, and a lot of times these machines don’t cooperate with each other,” he said. “We need a system that brings it all together so it’s useful to the farmer.”

Eric Taipale, CEO of Minneapolis-based Sentera, agrees and said customers expect to see data flowing into tools they already use. Instead of standalone products, they want a single digital platform where they can view all their drone data, satellite imagery and weather station analytics.

Additionally, drone pilots should not only know how to use the software and how to keep information secure, they also should be able to identify the best time to fly the fields based on the mission.

“They have to understand the temporal nature of the agriculture industry,” Lang said. “When conducting a flight they might be looking for something that happens in a short window of the plant’s growth stage. We need to be surgical about how we deploy drone pilots and make sure they get it right the first time, because there might not be another chance to get back in the field.”

FIELD MANAGEMENT

Equipment used on farms will continue to become smaller and start to replace people, Love said. He sees fleets of machines handling planting and other field work, leading to greater efficiencies.

“We’ll do a better job of managing the fields,” Love said. “Farmers always wanted to do these things; they just didn’t have the equipment. Now a corn planter will tell you how much seed you’re planting per row, how much down pressure the seeding unit has and what depth the seeding unit is, and it will record all that data as it’s planting.”

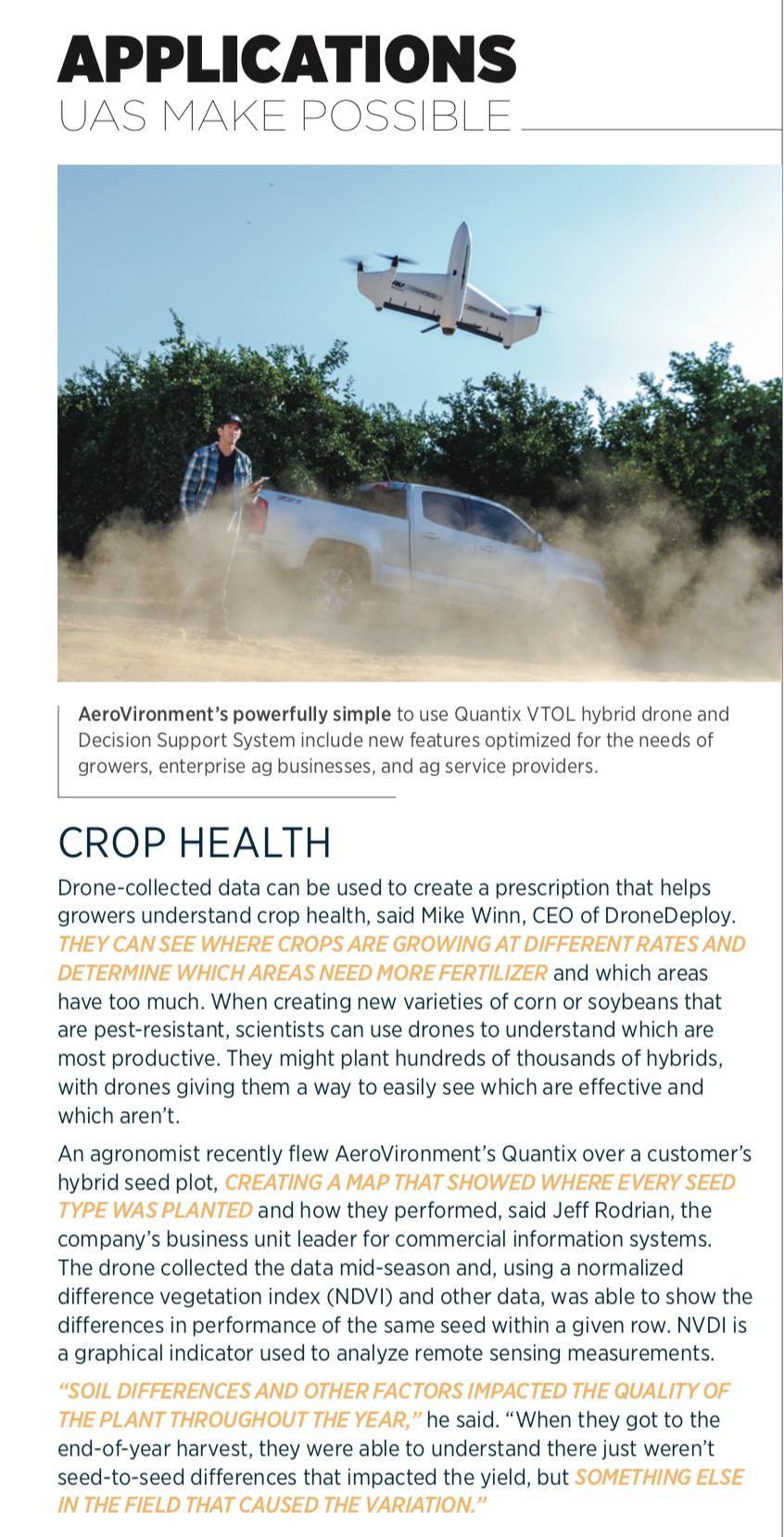

Incorporating automation and drone flights into operations will lead to more objective decision making and “an increased focus on managing farms on a smaller footprint,” said Jeff Rodrian, business unit leader, Commercial Information Systems for AeroVironment, the Monrovia, California, company behind the Quantix drone and the AeroVironment Decision Support System (AV DSS). Before, growers managed entire farms. Now it’s possible to measure yield to the acre or to the row, helping to optimize output.

THE CHALLENGES

While there are many benefits to implementing drones and other technologies onto a farm, agriculture and crop science are complex fields, said Jean-Thomas Célette, managing director of Switzerland’s senseFly. There’s often a learning curve for growers to overcome before they can fully reap the benefits. But as education improves and interest grows, Célette sees a “snowball effect driving adoption” coming in the next one to three years.

When collecting data, the right parameters must be met for it to be useful, Lang said. It’s important to be able to compare flights throughout the growing season. The first analytic has to align to sit on the second analytic and so forth. Most growers don’t know how to do this, which is where education comes in.

Then, of course, there’s managing all that data. Manufacturers are creating complete ecosystems to get over this hurdle, empowering customers to make decisions about the analytics they need.

“The big bug-a-boo right now is this is way more data than 99 percent of farmers know what to do with,” Love said. “They’ve been managing yield data off combines for years and have reams of data stacked up in their office that they’ve never done anything with because agriculture just wasn’t a very quantifiable business. A lot of business decisions were based on emotion. Now we can measure these things, but there’s a fair amount of the population that’s not used to that.”

Having easy access to the data collected, whether via drone or ground sensors, will help ease apprehension about the technology, Rodrian said. The ecosystem approach that companies like AeroVironment take makes it easier to integrate these systems so it’s not overwhelming.

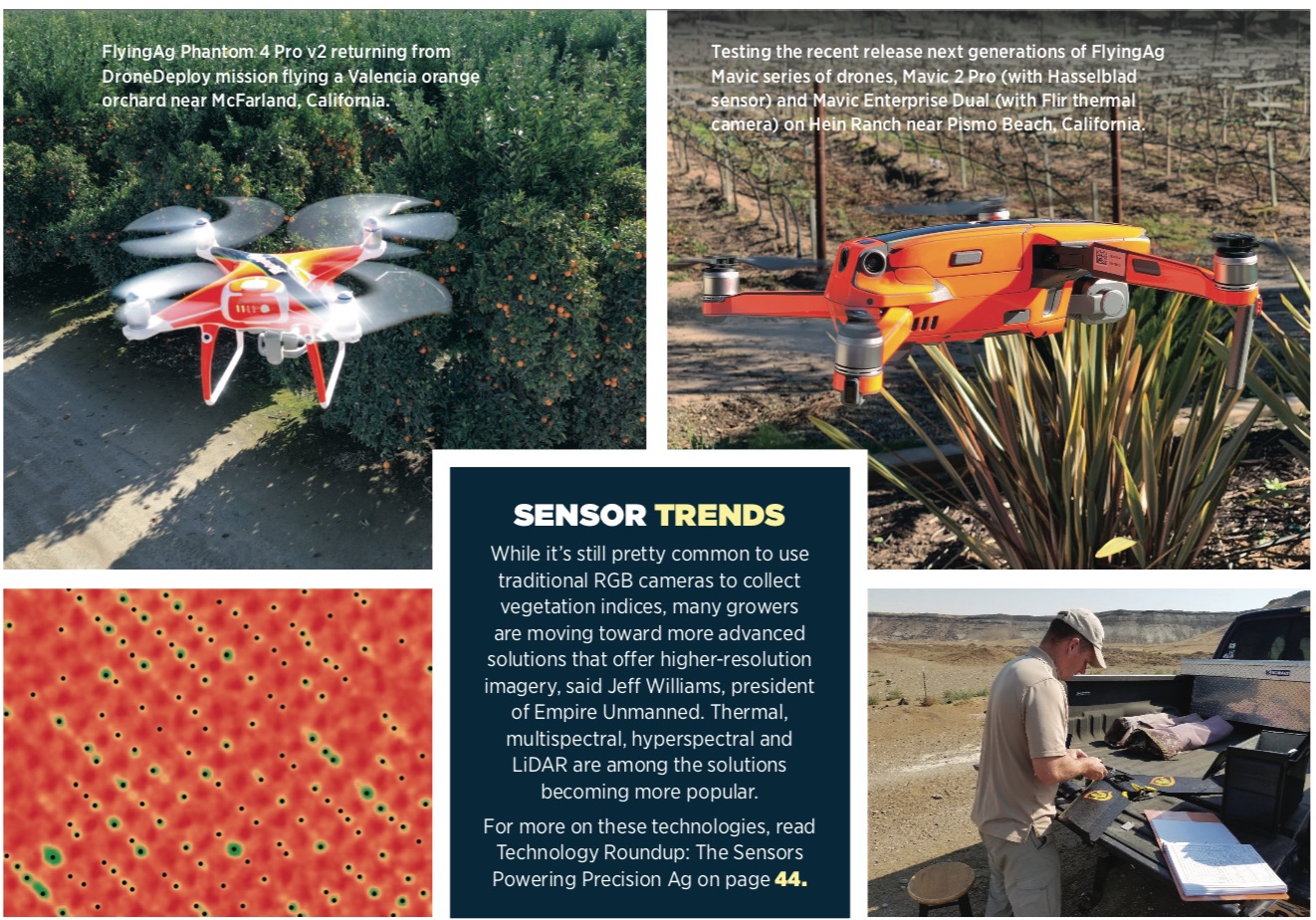

Using AI and deep learning makes it possible to harvest the data and make sense of it, said Jeff Williams, President of Empire Unmanned, of Hayden, Idaho. The data is more manageable when algorithms automatically search and sift through it, pulling out the analytics growers need most.

Speed is another goal. “For drones to be successful in agriculture we need real-time data,” said Chad Colby, owner of Colby AgTech, in Goodfield, Illinois. “Until recently you could fly a drone but you had to process the data somewhere else. Farmers need to be able to get the data as the drone is flying or as soon as it lands so they can make actionable decisions from that data.”

WHAT’S NEXT

• Sensor integration will continue, with more field sensor data being integrated into business processes.

• Sensors and robots, both on the ground and in the air, will be more specialized, Colby said. Farmers and agronomists will be able to collect very specialized data, translating into better information, improved efficiencies and cost savings.

• Continued focus on AI and machine learning. But for such technology to be effective, growers must collect quality data sets and have the right approach to solving the problems they’re trying to overcome.

• Many large organizations will go from a few to hundreds of precision-ag systems. Eventually, drones will be on every job site, taking off on a schedule to capture data and then feeding it back not only to the grower, but directly into ground-based machines.

• More research will be done on using drones to spray chemicals over fields. Flight time, payload and beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) limitations make this challenging, but Prof. Ampatzidis sees drone spraying as the future of the industry. There are already commercial systems developed for this task.

Automation, AI, deep learning and more coordination between air and ground robots as well as GIS will revolutionize the agriculture industry, Williams said. These solutions will become more common as the technology improves and as even the most skeptical growers put more trust in it.

“If growers aren’t using aerial sensing tools to gather data from the field, it will be impossible to compete,” Sentera’s Taipale said. “Humans will still have to go out and touch the crops and walk through the fields, but these technologies will make them as efficient as they can be with their time. They can go directly to areas where there are issues and perform high-value tasks. It will be everywhere.”