This summer, five orange unmanned surface vessels (USVs) set out from the US Virgin Islands, equipped with ruggedized hurricane wings to operate in winds over 70 mph and waves over 10 feet. Their destination: the heart of tropical storms wreaking havoc in the Atlantic. Their mission: to collect scientific data where it’s never been collected before.

This summer, five orange unmanned surface vessels (USVs) set out from the US Virgin Islands, equipped with ruggedized hurricane wings to operate in winds over 70 mph and waves over 10 feet. Their destination: the heart of tropical storms wreaking havoc in the Atlantic. Their mission: to collect scientific data where it’s never been collected before.

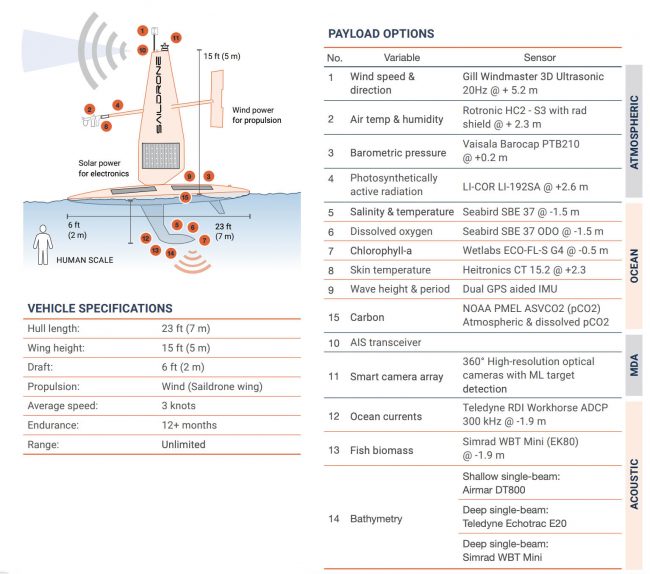

Saildrones, made by the Alameda, California-based company of that name, are autonomous ocean vessels designed to study the environment. They are highly maneuverable, wind- and solar-powered vehicles designed for long-range data collection missions. They collect meteorological and environmental data above and below the sea surface and can withstand the extreme winds and sea state present during a hurricane. The hurricane model is 23-feet long and carries four cameras, a dual GPS with inertial measurement unit (IMU) and several other sensors (see diagram at bottom of this article).

Saildrone USVs are under the constant supervision of a human pilot via satellite and navigate autonomously from prescribed waypoint to waypoint, accounting for wind and currents, while staying within a user-defined safety corridor.

Collaborating on the hurricane-huntijng missions are the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL) and Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML). This summer, the Saildrones took up stations in areas of the Atlantic Ocean that have historically seen a large number of storms. Scientists from PMEL and AOML worked together to pilot the vehicles into a series of hurricanes for testing and sampling. This mission created a foundation for PMEL and AOML to deploy a larger fleet of saildrones as part of a major field campaign for hurricane observations.

The biggest challenge to hurricane forecasting is rapid intensification, which can have a huge impact if a storm intensifies just before landfall. Hurricane Ida, which struck the Gulf Coast before traveling to the Northeast recently, grew from a Category 1 to Category 4 storm in less than 24 hours. Scientists need to understand the ocean processes that are occurring as intensity increases, which means collecting data immediately before and during a hurricane.

A tropical cyclone is a generic term for a rapidly rotating tropical storm with a low-pressure center and clouds spiraling toward the center of the system. In the Atlantic, they are also called hurricanes; in the Pacific they’re called typhoons.

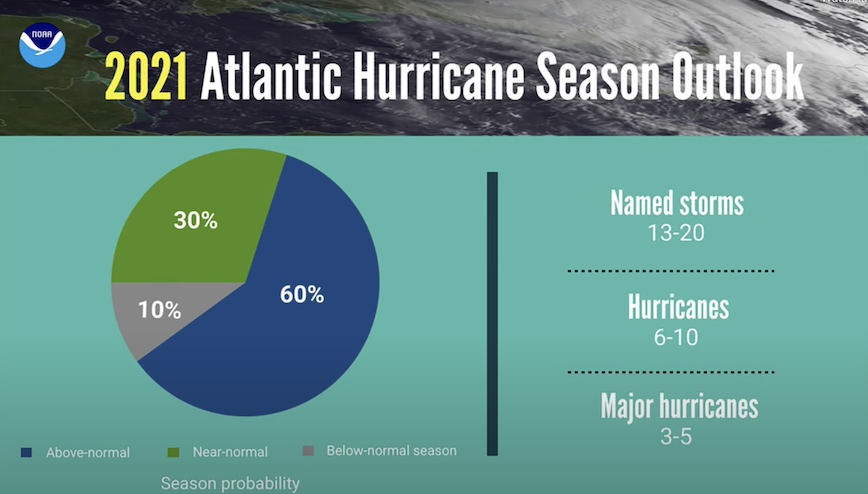

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center predicted a 60% chance that the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season will be above-normal, with 13–20 named storms. About half of those are expected to become hurricanes, and 3–5 of those are expected to become major hurricanes, Category 3 or higher.

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center predicted a 60% chance that the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season will be above-normal, with 13–20 named storms. About half of those are expected to become hurricanes, and 3–5 of those are expected to become major hurricanes, Category 3 or higher.

“The biggest gap in our understanding of hurricanes are the processes by which they intensify so quickly, as well as the ability to accurately predict how strong they will become. We know that the exchange of heat between the ocean and the atmosphere is one of the key physical processes providing energy to a storm, but to improve understanding, we need to collect in situ observations during a storm. Of course, that is extremely difficult given the danger of these storms. We hope that data collected with saildrones will help us to improve the model physics, and then, in turn, we will be able to improve hurricane intensity forecasts,” explained Dr. Jun Zhang, a scientist in the Hurricane Research Division at NOAA/AOML.

The 23-foot Saildrone Explorer is typically equipped with a 16.5 ft (5 m) rigid wing sail for forward propulsion. This wing is optimized for a wide range of sailing conditions, from very light to moderately heavy wind speeds. In November 2020, Saildrone began a five-month test of the first hurricane wing, shorter and ruggedized, in an area of the North Pacific where winter storms are frequent. Having proved itself, this model sailed the Atlantic hurricane season in summer 2021.

[Image above: Saildrone Explorer equipped with a hurricane wing, is a shorter, ruggedized wing optimized for tropical storm wind events Category 1 (74–95 mph/118–151 km/h) and above on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. All images courtesy Saildrone.]

[Image above: Saildrone Explorer equipped with a hurricane wing, is a shorter, ruggedized wing optimized for tropical storm wind events Category 1 (74–95 mph/118–151 km/h) and above on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. All images courtesy Saildrone.]

The USVs transmitted meteorological and oceanographic data from the eastern tropical Atlantic in real time including air temperature and relative humidity, barometric pressure, wind speed and direction, water temperature and salinity, sea surface temperature, and wave height and period. The data was also sent to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO)’s Global Telecommunication System (GTS) and disseminated to all of the major forecast centers—some 20 agencies worldwide, including NOAA.

The data will also be valuable to other groups, including the National Weather Service (NWS), and the National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS). NWS will use the Saildrone data to improve forecasting. NESDIS will align findings resulting from the Saildrone data with that of other observing platforms, such as gliders.

Saildrone has made about 100 vessels and plans to make more, including larger vehicles. The company’s USVs have logged over 10,000 days at sea and 500,000 nautical miles sailed from the Arctic to the Southern Ocean. In addition to the Atlantic hurricanes, Saildrones this year are engaged in other studies in the Atlantic, Pacific, Great Lakes, and a year-round mission to study air-sea carbon dioxide exchange in the Gulf Stream.