Thousands of years ago, intrepid sailors used the day’s leading-edge aids—landmarks and constellations, evolving nautical charts and sounding weights—to address the challenges of navigating the Mediterranean. Now, in that same region, UAVs are being recognized for their potential to deliver intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance (ISR) to tackle thorny issues such as competition for natural resources, the fights against terrorism and transnational organized crime, climate change and migration, reducing human workload while augmenting capabilities.

Many of the companies engaging in drone-based ISR in the Mediterranean are reluctant to discuss their activities, especially given sensitivities around current border-related issues. Schiebel and Leonardo are not.

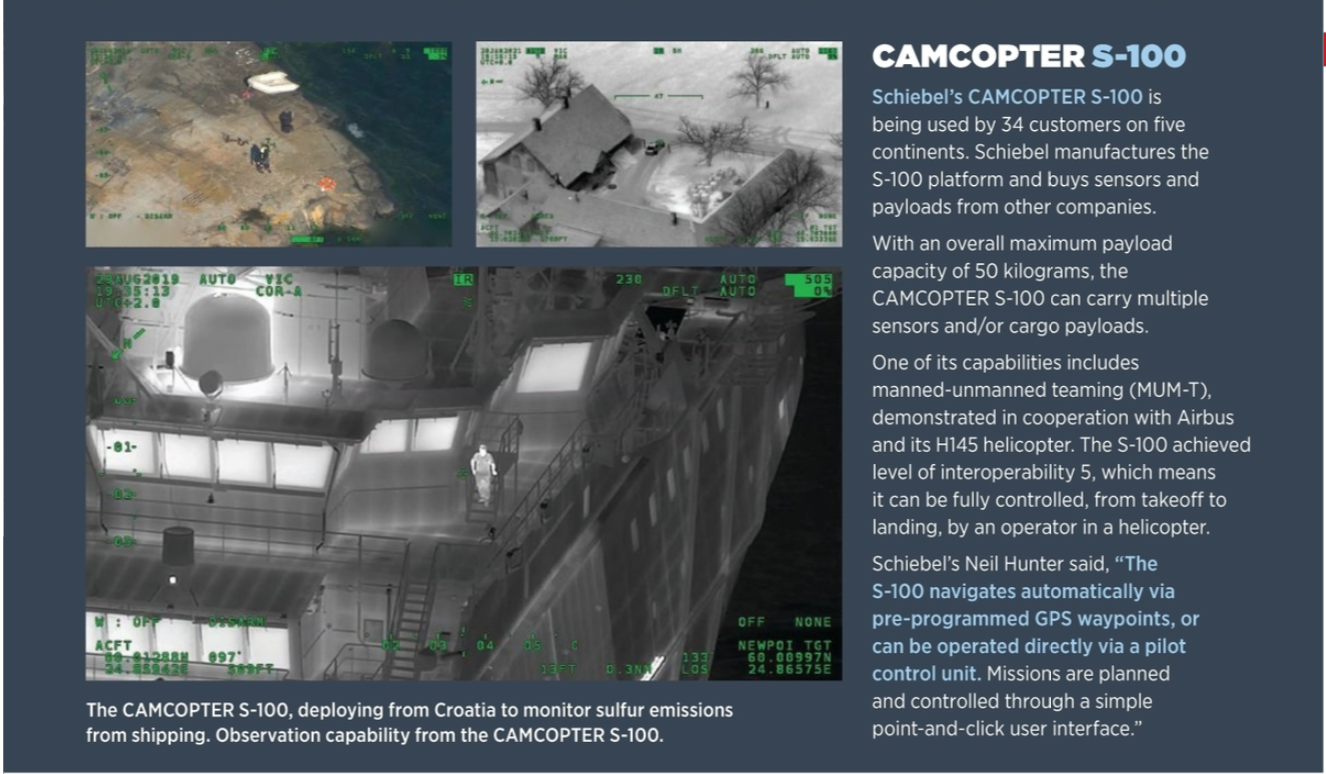

Schiebel Elektronische Geräte is a Vienna-based company carrying out drone operations for the European Maritime Environment Agency (EMSA). Under a contract awarded in 2018, it has flown its vertical-takeoff-and-landing CAMCOPTER S-100 UAS on numerous missions. Operations have involved maritime surveillance, coast guard functions, search and rescue, and emissions monitoring in a number of European countries, including Croatia, on the Adriatic coast.

“We used the CAMCOPTER S-100 specifically to measure ships’ sulfur emissions,” said Neil Hunter, director business development at Schiebel, “to check compliance with EU rules governing the sulfur content of marine fuels. Measurements are transmitted in real time through the EMSA RPAS (remotely piloted aerial systems) Data Center to the relevant authorities.

“Up to now, these kinds of missions have mostly been carried out with manned aircraft, which have a higher flight cost per hour,” Hunter said. “The use of unmanned air systems allows for dull, dirty and dangerous operations no longer needing to be carried out with manned aircraft, hence not endangering lives and being able to fly into hard-to-reach areas.”

The S-100 can stay airborne for more than 6 hours and can operate day and night. It is equipped with an Explicit “mini sniffer” sensor system, an electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) camera gimbal and an automatic identification system (AIS) receiver. Depending on the mission, other payloads and sensors can be used, such as the L3Harris WASCAM EO/IR camera gimbal, the Overwatch Imaging PT-8 Oceanwatch or the Becker Avionics BD406 emergency beacon locator.

SECURITY AT THE EDGE

The European Union, whose southern border is formed by the Mediterranean Sea, is striving to move beyond crisis management and toward a more coherent and sustainable border security strategy. The EU’s European Border Surveillance system (Eurosur) enables cooperation between the EU member states and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, also known as Frontex. Working together, member states and Frontex aim to improve situational awareness and reaction capabilities, preventing cross-border crime and irregular migration, and protecting the lives of refugees and migrants.

Meanwhile, increasing budgetary pressures have put the emphasis on leaner and more technically advanced systems for defense and homeland security operations. These solutions incorporate artificial intelligence, big data analytics, C4ISR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) systems—and UAVs.

Like EMSA, Frontex has been actively testing drones in monitoring operations in the Mediterranean. In 2018, the agency signed contracts for operations utilizing drones in the medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) class for border surveillance in Greece, Italy and Portugal, the stated aim being to explore surveillance capabilities and evaluate cost efficiency and endurance. Frontex has since tested unmanned aircraft in several real-life situations, including surveillance at sea, support for search-and-rescue operations and detection of vessels suspected of criminal activities, including drugs and weapons smuggling. It also has tested sharing provisions with multiple users in real time.

THE TRIAL OF LEONARDO

A key Frontex trial was carried out by Rome-based security/defense company Leonardo, in collaboration with the Italian Ministry of Interior and Guardia di Finanza (Italian Customs Guard). Fabrizio Boggiani is senior vice president airborne systems-electronics Italy at Leonardo. His view: “What has happened up to now is essentially experimentation and proof of concept, using unmanned drones or RPAS, generally speaking, for missions that can be called surveillance.

“During our work with Frontex, we took off from the Italian island of Lampedusa, directed by the Customs Guard, who were receiving instructions about what to do, where to go, from Frontex,” Boggiani said. Operations test the technologies themselves but also the cooperative arrangements and communications systems. Leonardo was called upon to undertake surveillance missions of active targets at sea.

“We would fly to the area of operations,” Boggiani said, “and then we would have a certain pattern of surveillance. It could be different in terms of size and shape, and in the frequency of runs over the same area, and then we would come back.” Leonardo used its Falco EVO for these operations. “The basic configuration for this type of mission, a surveillance mission, involves a maritime surveillance radar and two electro-optics airborne turrets that can accommodate an optical camera, infra-red camera, thermal camera and so on. Over the sea, we fly with an AIS, an automatic identification system, for recognizing the identity, friend or foe, of whatever is on the surface.”

The Falco EVO is a mature platform, easily adaptable to emerging situations. Boggiani said, “We can change the flight plan at any time, even when we are already in the air. We can change the area of operation, the pattern. We can change targets, and obviously if there is something of interest, the flight coordinator can tell us, for example, to follow a new target.”

In 2019, as part of the Frontex trial, one of Leonardo’s Falco EVO drone systems helped European police detect a criminal scheme. Leonardo launched the fixed-wing drone from Lampedusa, which then located a vessel engaged in criminal activity. The drone tracked the vessel until an enforcement operation could be launched by Italian authorities.

The Falco EVO is controlled by three operators working in a ground-based control station: one pilot, one payload operator and a ground control station manager. “There is also a mission coordinator,” Boggiani said, “who generally represents the end user. The mission coordinator understands the task that they want us to accomplish, and they give us instructions. We can fly autonomously, in the sense of fully autonomous lift-off and landing, and following a certain pre-planned route, but the instructions from the mission coordinator can change during a mission. So there are always people in the loop.

“Up to now, of course, we have used manned aircraft to do this kind of work, or it could be something on the sea, or from the coasts, like using radar, coastal radar or these types of things,” Boggiani said. UAV benefits include low emissions, small size and low weight. Also, long-distance and long-endurance flights are much easier to achieve without humans on board. “In one case we logged a 17 hour 21 minute uninterrupted flight with our Falco EVO out of Lampedusa. We can also do overnight missions.”

Another advantage is Leonardo’s service formula. “As an end user who only wants the information, you can avoid the need to train your people,” Boggiani said. “You can simply buy the information you want. The Italian government has taken this service-based approach; they are not buying drones; they are buying flight hours and data and information provided by sensors onboard the drones. It is the same formula we have been applying since 2013, when we had the first contract with the United Nations for drone services supporting a peacekeeping mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Obviously, here we are talking about surveillance of an institutional or non-military nature. We are not talking about things that can be linked to military or defense, where it might be a different story.”

WHO DOES WHAT

Once again, a key element of interest for Frontex has been how to coordinate operations involving different technical innovations and control systems across regulatory bodies and national jurisdictions. Though European countries on the Mediterranean may be part of the same European Union, each country still maintains control over its own airspace, often under unique provisions.

Thus, all Frontex trials have been carried out in close cooperation with national aviation, security and/or defense authorities. The Leonardo/Italian Customs Guard involved a total of 300 flight hours focused on illegal cross-Mediterranean movements and trafficking from the North African coast and inland to Italy. The Greek trials featured a similar scope and arrangement, involving Hellenic coast guard, civil and air force authorities. Leonardo also has been part of a similar domestic Italian trail, involving another set of cooperative arrangements.

For bigger drones—the Falco EVO has a maximum take-off weight of 650 kilograms—regulations in Europe are not yet fully in place and working guidelines are generally derived from manned aircraft regulations. For special missions, coordination is handled by the appropriate national authority for traffic control. In Italy, for example, that would be INAC (Instituto Nacional de Aviación Civil).

As for the Frontex trials, Boggiani believed that Leonardo is the only operator so far to have obtained a permit to fly covering two European nations, in this case Italy and Malta. This was necessary due to the particular routes flown out of Lampedusa, which is situated just 15 nautical miles from the Maltese flight information region.

OPPORTUNITIES, MULTITASKING, DATA-SHARING

Drones and other unmanned systems are now operating in increasing numbers, monitoring sensitive and strategic assets and resources, both commercial and public, and collecting information on hostile or clandestine activities.

Military organizations will without doubt continue to use drones for ISR. Boggiani said he expects institutional, governmental applications, generally involving surveillance, to increase for inhabited areas. Applications can include monitoring of national critical infrastructures and valuable commercial assets, or in the case of disasters or emergency situations, both on land and at sea. “For the time being we are flying more over the sea or over low-populated areas. With improving specs and certification, we can extend the areas where drones can fly.”

Multitasking is another area of expanding interest. The Falco Xplorer is a new fixed-wing drone by Leonardo, with an 18.8 meter wingspan and a 1,300-kilogram maximum takeoff weight, enabling multisensor, multi-end-user, long-endurance missions. “You can put on board such a big number of different types of sensors, you can perform one mission serving multiple purposes, so you save time and reduce emissions.” The same service-based business model applies, with users purchasing information, not hardware.

In the Mediterranean in particular, Boggiani said better coordination is a pressing need. “What we see more on the Mediterranean is different entities trying to work together in a more efficient way. In military applications, interoperability and connection and networking of information are very well developed. This is something that could happen with institutional applications. Bringing together air assets, ground assets, marine assets, and so on, we can share information coming from different sources.”