Uncrewed surface vessel Maxlimer from SEA-KIT helps scientists worldwide get data more safely, more quickly, more efficiently and more comprehensively.

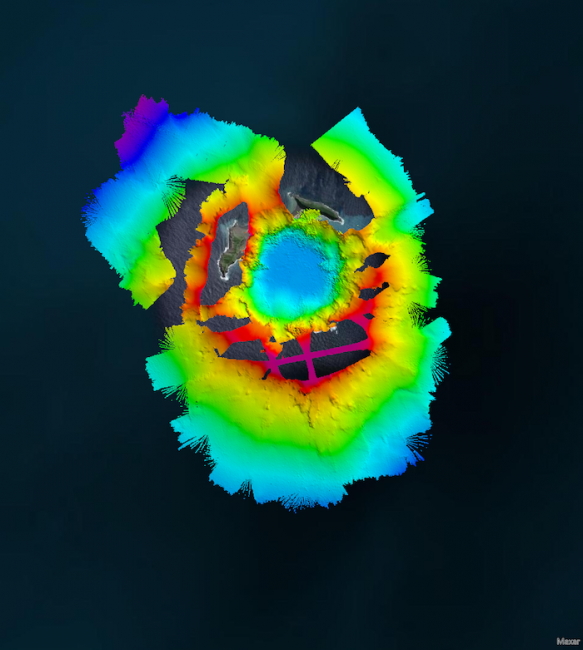

When the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano erupted in the South Pacific in December and January, it sent a plume of ash 36 miles in the air and set off a tsunami that reached Japan and the Americas.

Not too long ago, geologists might have had to take some risks to get the answers they needed about the biggest volcanic eruption in the world since 1883. But now they don’t have to, thanks to a specially equipped uncrewed surface vessel provided by SEA-KIT, an uncrewed shipbuilder and operator based in Essex, U.K.

The 12-meter Maxlimer has helped scientists get the data they need more safely, more quickly, more efficiently and more comprehensively than they might have even a few years ago.

A job for an Uncrewed Vessel

SEA-KIT got the assignment in March.

Initially, a conventional survey ship was sent by New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) to investigate, but being crewed, it could go only so far. “They mapped the entire area outside of the caldera, but the risk of entering or going over the top of the caldera was too great, really,” Ashley Skett, operations director of SEA-KIT recalled.

That’s when The Nippon Foundation, a major Japanese philanthropy, called on SEA-KIT to refit one of its 12-meter uncrewed surface vessels to spend more time in the area and sail right over the post-eruption hollow.

A SEA-KIT crew packed the diesel-powered vessel and equipment into two shipping containers, which were then transported by cargo ship to the South Pacific and reassembled. In addition to the usual equipment, they added a multibeam echo sounder to survey the seabed and a new winch that can drop sensors down 300 meters to obtain direct water column measurements. They also packed a conductivity temperature depth instrument and a miniature autonomous plume recorder designed to detect chemicals common in hydrothermal plumes.

The first two stages of the mission were conducted in July and August: first, a three-day reconnaissance for planning; then a five-day survey, which the Maxlimer completed despite some 3-meter seas.

The USPs of the USV

Despite the fact Hunga-Ha’apai is in an extraordinarily remote place—40 miles north of Tongatapu, the main island of Tonga, about 1,500 miles north of New Zealand and mostly underwater—geologists have been able to collect enormous amounts of data in real time, skippered by SEA-KIT pilots at the company’s headquarters 10,000 miles away.

“We can have experts from all over the world, at the top of their fields, dial into the boat, see what’s going on and offer their expert input.”

Ashley Skett, operations director, SEA-KIT

The scientists have even been able to do their work faster than on a conventional survey ship, according to SEA-KIT. Conventional ships can’t operate 24 hours near an underwater caldera for safety reasons, because the signs that a new eruption is brewing are less easily seen at night, Skett explained. That’s a serious consideration given NASA’s estimation that the Hunga-Ha’apai eruption was hundreds of times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Besides needing only 2% of the fuel a conventional survey vessel with a human crew would require to do similar work, according to Skett, the Maxlimer’s automation has enabled many more people to take part in the expedition. Having no one on board means it’s possible to have many people on board: for this project, surveyors and scientists based in Australia, Egypt, Ireland, Mauritius, New Zealand, Poland and the US have all monitored and reviewed the data as it’s gathered.

The expedition’s teams invite others to stop by as well. “We can have experts from all over the world, at the top of their fields, dial into the boat, see what’s going on and offer their expert input,” Skett said.

Scientists connected with the project say the effort has paid off. “It is incredibly exciting to be able to look down into the caldera and see volcanic plumes. We now know that at its deepest point it is around 850 meters deep, more than the height of two-and-a-half Eiffel Towers,” said Dr. Mike Williams, chief scientist-oceans at NIWA, according to a release. “The data and imagery that Maxlimer has brought back is astounding and is helping us to see how the volcano has changed since the eruption.”

Essex, we Don’t have a Problem

For SEA-KIT too, the experience has been valuable. Although the difference in latency between operating the Maxlimer in U.K. waters compared to the Pacific is unnoticeable, Skett said that his team did realize they needed to write additional software to prevent the winch from continuing to unwind if Essex lost contact with the boat.

Meanwhile, the adventure continues. After a second round of surveying in the caldera, the Maxlimer may have another mission before she leaves Tonga: scouting a new undersea route for data cables cut and buried during the eruption.

Photo/image courtesy of SEA-KIT, NIWA, Nippon Foundation, TESMaP.