Experts project the unmanned underwater vehicles (UUV) global market to hit the $5.2 billion dollar mark by 2022. This is largely due to increasing demands for commercial subsea construction-related applications, including surveys, seabed mapping and pipeline inspections. Even so, the governing legal regime for UUVs remains uncharted while the international community is just now skimming the surface of regulatory waters, with a focus on autonomous surface ships.

INTRODUCING UNDERSEA DRONES

UUVs—submersible unmanned vehicles—are divided into two categories: remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). ROVs are linked and controlled by a person or crew on either land or neighboring craft via a tether that houses energy and communication cables and a related tether management system, as well as built-in sensors for video (camera and lights), thrusters, a flotation pack, sonar and other instruments. AUVs, on the other hand, are untethered in every sense of the word: they operate without an umbilical cord or a human “in the loop,” often preprogrammed with waypoints and a designated task.

UUV tech continues to evolve and opportunities continue to expand.

SKIMMING THE SURFACE

From the use-case standpoint, UUVs are not new. Originally deployed as mine-sweepers, by the 1980s UUVs had entered the commercial market in lieu of divers to support historical exploration and salvage. They also became useful for underwater infrastructure construction and inspections in the offshore oil and gas industries—today, the largest ROVs can dive as deep as 20,000 feet. Ever-increasing energy needs have led to emerging wind and solar power markets, generating additional underwater infrastructure needs.

Advances in UUV tech such as higher-resolution cameras, better manipulator arms and more sensitive sonar have reduced the time needed to locate and inspect items, consequently opening an ocean of other markets. Constructing bridges, piers, off-shore mooring buoys, ferry lanes and highways often occurs in the littoral (nearshore) area. Bridges sometimes house gas, electrical, communications and other utilities, and require routine maintenance, inspection and continuous oversight. UUVs can inspect the deepest water under these structures, providing data that enables the construction industry in ways never before possible. A prime example, the Blueye Pioneer, is equipped with powerful LED lights, a high definition fixed camera and four thrusters that cut through low-visibility water with agile maneuvering. The benefits of these “underwater eyes” include quick startup, portability, minimal training, easy operation/control and low vehicle maintenance.

It’s no wonder, then, that UUVs are big business globally. So, what rules apply?

WAVETOPS AND SEA LANES

General maritime law consists of a constellation of treaties, statutes, regulations and judge-made law. The seminal treaty, the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), defines State rights and responsibilities with respect to the world’s oceans. The U.S. has signed, but not ratified, this treaty. However, to the extent that its provisions consist of norms arising from State practice, they are considered customary international law (CIL), which the U.S. is bound to follow.

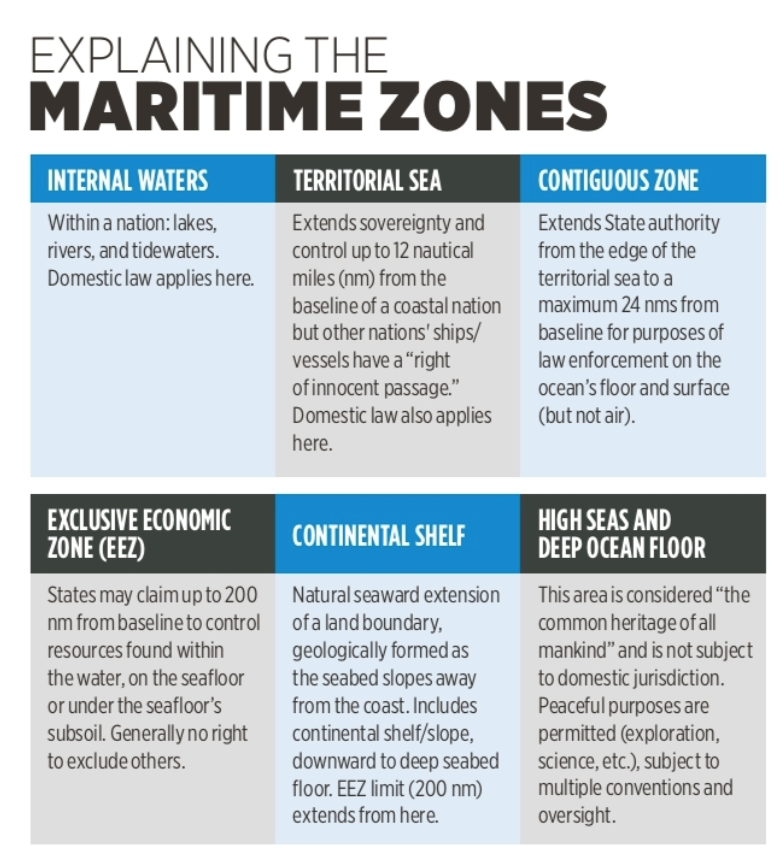

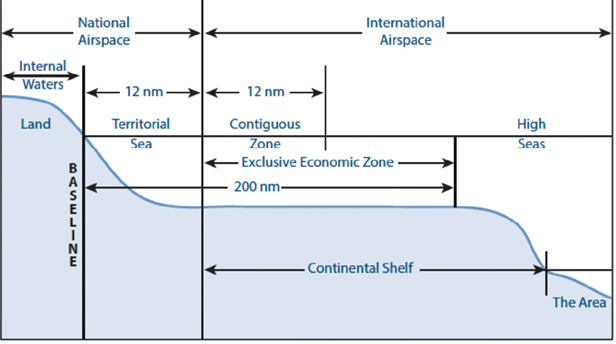

The keystone of UNCLOS is freedom of the seas. To ensure this, UNCLOS created maritime zones, similar to the classes of navigable airspace. (See Chart.) A nation’s most robust authority lies within a country’s internal waters and the territorial sea that extends 12 nautical miles (nm) from its shores. Claims reach out to the contiguous zone (24 nm), the up-to-200-mile-out exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and the high seas, which offer different levels of national control and freedom of the seas.

For the undersea construction industry, the EEZ is especially important. There, coastal States have the exclusive right to construct and to authorize and regulate the construction, operation and use of, among other things, installations and structures for economic purposes and those that may interfere with coastal State rights (UNCLOS Art. 60). Still, such activities must be conducted with due regard for the rights of other nations. Cmdr. Tracy Reynolds, a member of the Navy JAG Corps* explains, “To simplify, ‘due regard’ means that all surface, subsurface and air maneuver must be conducted in a manner that does not interfere with the rights of other States or the safe conduct and operation of other vessels or aircraft.”

Another key international regime providing for the safe navigation of ships is the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea of 1972 (COLREGs). Applicable to the high seas and navigable waters, it is codified in U.S. law at 33 U.S. Code §§ 1601-1608.

Domestic law is critical to operations in inland waters, territorial seas and, in many respects, in the EEZ and on the high seas. The U.S. Inland Rules of the Road, 33 U.S. Code §§ 2001 et seq., specifically govern the operation of vessels in U.S. waters. Domestically, ships are also subject to domestic lifecycle safety, environmental, labor, training, manning and security regulations, to name a few. Domestic law and regulations govern ship construction, maintenance, repairs and inspections, and have global impact for U.S. flag vessels. Congress has designated the Coast Guard to provide these rules, just as the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) does for aircraft (USCG regulations at CFR Volume 46). Legal liability can ensue for non-compliance.

COLREGs are applicable on waters outside of established navigational lines of demarcation. These COLREGs Demarcation Lines delineate those waters upon which mariners shall comply with the Inland or International Rules. COLREGs Demarcation Lines are listed in 33 CFR 80 and the Navigation Rules and Regulations Handbook. There is also a Boundary Line, which the USCG defines as “the dividing point between internal and offshore waters for several legal and regulatory purposes” (46 CFR part 7).

Confused yet?

DIVING DEEP

All these legal obligations can seem as clear as murky waters on a dark day, further muddled by the fact that maritime legal regimes were created for surface ships, submarines and aircraft with humans on board. For example, Rule 2(b) of the COLREGs requires the owner, master or crew of a vessel to ensure that due regard “shall be had to all dangers of navigation and collision and to any special circumstances, including the limitations of the vessels involved, which may make a departure from these Rules necessary to avoid immediate danger.” For a UUV, though, who is the master or crew to whom these responsibilities apply? Similar to “see and avoid” in the UAV world, Rule 5 of COLREGs requires that vessels have a lookout to prevent collisions. Do acoustic and visual capacities on UUVs satisfy Rule 5? And, if a UUV is not a vessel, do the COLREGs apply at all? Currently, there is no controlling definition of what constitutes a “vessel” or “ship” in the law of the sea or CIL.

The list of unanswered questions is long and international maritime experts are trying to keep pace with the tech. In the last few years, the Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) of the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a specialized shipping-focused agency of the United Nations, launched a scoping exercise to review 50 IMO legal instruments relevant to maritime autonomous surface shipping (MASS). During Stage 1, the group selected eight conventions that were considered most relevant to MASS, including the COLREGs.

What about UUV? Renowned scholar and maritime law expert James Kraska, chairman and Charles H. Stockton Professor of International Maritime Law, U.S. Naval War College, stated in The Journal of Ocean Technology (“The Law of Unmanned Naval Systems in War and Peace”) that the law of the sea applies “’mutatis mutandis’ to unmanned systems operating in the same domain. (“Mutatis mutandis” is a Latin phrase that means “changing those things that need to be changed.”) Perhaps.

Add to the equation domestic law. U.S. maritime rules do not address UUVs, with few exceptions. For starters, the Coast Guard national vessel registration process, mandatory for all commercial vessels and voluntary for large recreational boats, does not explicitly apply to ROVs. In fact, a search of USCG regulations (46 CFR) elicits three hits for “ROV”—alternate compliance for inspecting vessels (§ 71.15 – 5), hull examinations (§ 71.50 – 27) and after-accident investigations (§ 71.40).

Consequently, while hundreds of treaties, agreements and codes provide a complex legal and regulatory regime for navigation on and above the seas, especially for such disasters, according to Fordham Law School Admiralty Professor Lawrence B. Brennan, a retired Navy JAG Captain, there is not a lot of law governing subsurface navigation. Maritime law expert, current director of compliance and chief counsel (technical solutions division, HII-defense and federal solutions) at Huntington Ingalls Industries and Rear Admiral, U.S. Navy (Retired) Kirk A. Foster concurs: “The regulation of commercial sector, unmanned remotely operated undersea vehicles remains in an evolutionary phase.”

UNDERWAY

Tech has enabled us to go deeper and cheaper in our globe’s seas, yet we’ve just dipped our toes into UUV regulatory waters. As Professor Brennan has observed, “The general maritime law and federal statutes establish minimal legal standards. The entire admiralty law regime needs to be revisited to maximize the use of UUVs before serious investments can be prudently made.”

Rear Admiral Foster advocates for collaborative, comprehensive and conclusive guidance “before there’s a disaster, such as a UUV damaging an underwater wellhead cap or a pipeline resulting in cataclysmic environmental damage, and the imposition of a reactionary regulatory scheme prepared in haste.” He believes the current state of affairs “represents a rare opportunity when industry, U.S. regulators and policy/legal experts can and should as a team develop efficient, effective and commercially feasible standards that promote safety and commerce.”

Until then, domestic legal obligations and international conventions provide useful starting points for determining appropriate standards, such as the established principles of due regard. Commercial entities preparing for UUV ventures should integrate these concepts now to avoid costly and time-consuming re-work later when they are explicitly required. Bon voyage!