Flying unmanned aerial systems is just part of the workflow at the 10 Barrick Gold Corp. mines scattered throughout North and South America.

The company first began using unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) in 2012, and since then has embraced the many benefits drones bring to mining sites, from increased safety to enhanced efficiencies, said Iain Allen, senior manager for mining information technology. Today, most of the sites deploy drones, such as senseFly’s fixed-wing eBee, at least three times a week, with a site in the Dominican Republic flying every day.

At first, the Barrick mines focused on stockpile volume measurements—probably the most common use for drones in the mining industry to date—and then added orthophoto mapping. The application possibilities seem endless, which is why Allen expects most mining companies to invest in UAS for measurement, monitoring and maintenance tasks in the next few years.

“Everyone in the industry is realizing the value of drones. They’ll soon become a standard practice,” Allen said. “There’s just too much value not to have one.”

Stockpile Measurement

Before drones, measuring stockpiles was a labor-intensive job that took a lot of time, said David Shearer, vice president of marketing at Kespry, a company that delivers end-to-end drone solutions. Getting the measurements meant climbing on the stockpiles with GPS equipment, a dangerous, physically demanding proposition that most surveyors prefer to avoid. The surveyors would take multiple data points and then map them to estimate the stockpile’s size—not the most accurate way for a business to manage and keep track of inventory.

John Davenport of Madison Materials and Whitaker Contracting has spent many years walking stockpiles, trying to keep his footing while the rocks slipped out from under him, hurting his ankles.

Those walks were a struggle, but were necessary if he wanted to take accurate measurements of those piles using GPS systems. To perform certain aspects of his job he also had to work in yards where dangerous, heavy equipment was operating. But for the last year and a half his job has become less time consuming and much less dangerous because he’s been using a Kespry drone to perform stockpile measurements as well as various monitoring tasks.

“Before it used to take me three days per quarry to actually gather the field data. Then it would take me a couple days to crunch the numbers and put together the reports. Within a week I could have numbers for one of the quarries. In a little over two weeks I’d have all my numbers. We’d do that once a year,” Davenport said. “But the time savings the drone offers is so phenomenal it’s allowed us to get that snap shot so much faster and so much easier. We’re now doing our complete inventory every month. That’s a huge statement. I can’t tell you how big that is.”

The Kespry automated drone flies a preplanned route, simplifying operations, then automatically uploads its data to the cloud. Within hours the team has processed, usable data in the form of a 3-D model, Shearer said. They can rotate the model to see different aspects of the topography and get a true reading of the stockpile’s volume.

Davenport also uses his drone to monitor construction sites and to plan other sites where he takes high-resolution images that can be used for a variety of purposes including site models. His customers love the fact he can link them in during the flight—saving everyone valuable time and money. He said he will soon receive the newest model, the Kespry Drone 2.0, which is lighter, faster and features more advanced technology.

Davenport also uses his drone to monitor construction sites and to plan other sites where he takes high-resolution images that can be used for a variety of purposes including site models. His customers love the fact he can link them in during the flight—saving everyone valuable time and money. He said he will soon receive the newest model, the Kespry Drone 2.0, which is lighter, faster and features more advanced technology.

“Because I’m the guy walking the stockpile I’d say the biggest benefit is safety, but with regard to the company I’m also going to say cost savings is a big benefit,” Davenport said. “And productivity. Everything it does it does better than I could do and faster than I could do. And it takes me out of harm’s way. It has changed my working life a great deal. I’ve reached an age where the physicality of it was about to get beyond me. The drone allows me to continue doing something I love to do.”

Shearer has worked with several clients who are equally enthusiastic about the benefits drones bring to stockpile measurement, with one saying a job that once took about two days now takes about 10 minutes. Moreover, making it easier to take inventory makes it possible to more fully track changes. Typically, stockpile measurements are only taken once a quarter or just a few times a year. With a drone, these measurements can be taken as often as once a week or once a day—helping mine operators make better business decisions.

“For us the biggest benefit we realized so far is the stockpile volumes,” Allen said. “At most of our mines we don’t have enough available space to have separate stockpiles for different ore, so we need to know which ore is in each pile. The mill has to know what we’re sending so they can process it appropriately. If we get it wrong, it reduces our return on gold and that costs us money. A 3-D model of a stockpile is extremely useful and it’s much faster than conventional survey techniques.”

It’s also more accurate. When people take the measurements by hand with a laser scanner, which is what his team used to do, they can’t account for irregularities on the top surface because they can’t see them, Allen said. UAS look down on the piles, so they can see depression caves and undercuts—giving mine operators more accurate volumes. And of course there’s the benefit of cost. Laser scanners typically used for this kind of work tend to run about $180,000, he said, while he can buy a drone for about $20,000 and fly it without disrupting operations.

Monitoring and Mapping

Stockpile measurement might be the most common use for drones in the mining industry, but other uses are gaining traction – especially monitoring.

The topography of open pit mines is constantly evolving and drones offer a good way to keep track of those changes, said Lorenzo Martelletti, sales and marketing director for Pix4D, the company that developed the Pix4D Mapper Pro to turn the data drones collect into 3-D models, ortho mosaics and other assets. One of the typical monitoring uses is pre- and post-blast analysis.

Before a blast, it’s important to make sure drill holes are aligned and that no one is in the area, Airobotics CEO and co-founder Ran Krauss said during a mining talk at the UAV Commercial Expo in November. Workers can then look at the 3-D model created after the blast to ensure they achieved their objective. It also gives them an updated map of the mine after the blast.

Pix4D recently worked with clients in Ohio and West Virginia who deployed UAS for stockpile measurement and blast monitoring, Martelletti said. They wanted to find a way to make various processes safer, so they flew a DJI Inspire 1 and a Phantom 2 Vision Plus over stockyards, capturing images at a 45-meter altitude to achieve a 2 cm ground sampling distance (GSD). The 3-D model of a blast bench created from those flights was combined with data from a borehole tracking system to identify areas of weakness and over-confinement. The results and spatial information collected will be used for later analysis, engineering applications of potential post-accident comparisons, and historical records.

Allen also relies on UAS to monitor large construction projects, he said. Before, if they brought in a contractor to rebuild a storage facility, for example, they’d just have to accept his progress report because they had no way of actually monitoring what he was doing. With a drone, Allen has a bird’s eye view of the entire site, so when a contractor tries to tell him part of the project is complete when it isn’t, all he has to do is pull up an image or video from the drone to show the contractor he knows that isn’t true. That changes the relationship immediately and keeps contractors honest.

UAS are also invaluable during incidents, Allen said. The ability to get a picture from above helps keep workers safe as they try to figure out what happened and how they can prevent it from happening again.

“After a storm or natural event they can assess the damage and control it,” said Matteo Triacca, business development and product manager at senseFly. “They can send in a drone instead of personnel after an incident to assess and make strategic decisions on how to intervene.”

UAS, for example, can map where water is the highest during a flood as well as assist with recovery efforts during natural disasters, Insitu Pacific Managing Director Andrew Duggan said. And when injuries happen, information from a UAS can help personnel get a direct view of the scene so they can quickly provide resources and rescue the victim.

Oversight and Reclamation

The Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, a government organization charged with overseeing coal mining operations and reclaiming abandoned coal mining sites, started looking into how drones could help them with their work back in 2011, Supervisory Program Specialist Natalie Carter said. They didn’t know much about the technology back then, but started proof of concept tests to see how UAS could help save them time and money while also limiting the amount of walking employees had to do on what’s often rough terrain. The team has used the RQ-11 Raven from AeroVironment and the Honeywell RQ-16 T-Hawk to assist with their oversight work, to observe potential problems with reclamation and to identify evidence of underground mine fires.

“We’re viewing the information in real time and looking for potential problem areas,” Carter said. “We’re using infrared and thermal cameras to identify water on the mine site, whether it’s supposed to be there or not. We’re able to derive from that data, through the infrared camera, vegetation health, whether it’s stressed or healthy, and then we get an idea of the vegetation coverage, which is useful. We’re also able to determine the surface configuration of mine sites to see if they’re being put back the way they were planned to be put back.”

When mining companies write a mining plan and the state approves the permit, they have to explain how they’re going to reclaim the site—which is very detailed work. This organization makes sure that original plan is adhered to, Carter said, which usually requires personnel to walk the mines. The mines she works with in West Virginia can be anywhere from 300 acres to multiple complexes with 10,000 acres, and this work could take one or more days to complete. With a UAS they can cover about 200 acres an hour or 9 to 12 permits in three days.

And if the team spots any problems while using a drone, because they receive that information in real time, they can go to any questionable areas and take a closer look, Carter said. Instead of two people spending hours walking the ditch perimeter in rough terrain, making sure stable discharge points are in the right location and looking for other potential problems, they know exactly what areas need attention—leading to huge time savings and a much safer process.

Now that Carter and her team know the benefits UAS provide, they’d like to purchase a drone of their own. (The ones they use now are shared, which means they can only fly a few weeks out of the year.) While Carter doesn’t know when they’ll get approval to make this purchase, she does have an idea of the features she’d like it to have, which include something that’s battery-operated, user friendly, easy to maneuver and transport with the ability to easily change out different types of sensors.

“I’m sure we’re only scratching the surface of what this technology can do,” Carter said. “There’s the potential to have better mine maps and to observe reclamation areas that are difficult to get to. That’s timesavings as well as safety. I don’t think there are any limits to what we will be able to do with this technology.”

Other Applications

Until recently, Allen and the Barrick Gold mines only flew visible light, photogrammetry cameras on their drones and focused on creating 3-D models and orthophoto mapping. While he hasn’t had a chance to fly it yet, he recently invested in a DJI Inspire with a FLIR thermal camera—which has opened up a host of new opportunities.

Allen intends to use the thermal camera for infrastructure inspection, to identify hot spots on stockpiles (which could lead to sulfur self-combusting and turning to toxic gases) and to help with wildlife preservation, Allen said. The Sage Grouse, a threatened bird species in Nevada that may soon end up on the endangered list, often nests near one of the mine sites. These nests show up as hot spots, so if they use a thermal camera, Allen and his team will know exactly how many there are and from there determine how best to manage them. UAS equipped with thermal cameras could also help monitor pipelines that run from the processing plant to the storage facility to pick up leaks.

While there’s plenty of opportunity and potential applications, Allen sees thermal cameras offering the largest benefits in infrastructure inspection, he said.

“Instead of having a substation, a transformer or one of the electrical power lines fail, we can find problems before they happen, which eliminates downtime,” Allen said. “Every hour we’re not producing costs us money because that’s gold we’re not getting. It also helps with safety. It’s better to find issues before something breaks than to have to fix it afterwards.”

Allen is also thinking about investing in hyperspectral cameras for mineral exploration, he said. These cameras can pick up alterations in the rock, which is an indication of potential gold. They could also perform environmental surveys to look for things like vegetation stress.

Equipping a UAS with a gas sensor might also offer safety benefits, Allen said, enabling mines to improve leak detection. Typically they send a robot into the mine to check for leaks, but if the source of the leak isn’t on the ground, the robot might miss it. Sending in humans is dangerous, making this an ideal job for a UAS.

Mines of the Future

As the technology continues to evolve, UAS will become more and more common at mine sites all over the world. Mine operators will increasingly learn to rely on the technology, Allen said, and make the necessary changes to their workflow and their culture to streamline drones into their regular operations.

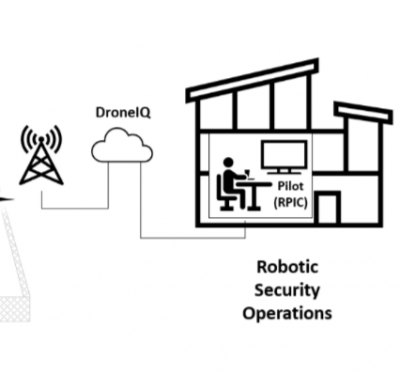

“They’re starting to really grasp the value of having the capability there on a consistent basis,” Duggan said. “In the future, we’ll have multiple systems operating safely at mine sites, and these systems will be remotely controlled. I think eventually the goal is to have fully autonomous mine sites where those systems can operate on a daily basis to gather information. The robotic mine of the future is really the path. There will still be some people working but a lot of the systems that gather the data for site planning will be automatic.”