For the last 10 years, MotionDSP has primarily focused on providing image processing and computer vision software for military applications, but like many others, the company has recently shifted its focus to the growing commercial UAS market.

The team at MotionDSP knows how video can help drones deliver the end user more accurate, timely information, whether the drone is being used in applications for agriculture, oil and gas, or search and rescue, among others. That’s why MotionDSP is collaborating with several universities to find ways to provide advanced software along with expert analyst training to help develop new perspectives using video.

Collaborators include Auburn University, the University of North Dakota and Kansas State University.

“Universities are the center for research into these specific industry applications that need drones,” MotionDSP CEO Sean Varah said. “We want to be there. We are in a transition where drones have been used by military for a long time. The military is the No. 1 user of drones and live video. That capability is becoming available in the commercial world. We have to adapt. We need to build new solutions or change existing solutions to meet these new needs. We want to be on the ground floor with these folks so we can understand the problems and come up with solutions.”

Why Video

Many small drones are set up with the capability to take images, but not video, Varah said. Images are a great tool and can be put together to tell a story, but video can give you information in real time—and that can be critical in some of these applications.

Let’s take a cattle rancher who discovers he’s missing two cattle out of the 500 he owns. A still image from a drone can tell the rancher where that cattle is, but by the time someone gets to the location the cows will likely be long gone, Varah said. A video detects motion, and can send out the location in real time.

“You want to be able to get to them quickly. The drone will send back live video feed and will look at the video the way a human would, detecting anything moving on the ground,” Varah said. “The drone would then alert the farmer to let him know movement was detected in these GPS locations. That would narrow the search down, and instead of driving the truck around an enormous area, the farmer can go to the specific places where movement was detected.”

This is a problem MotionDSP heard about straight from farmers, Varah said, and they’re currently working with the universities to come up with a solution that will work best, including determining how the drone will deliver the information, whether that’s sending the GPS location straight to the farmer’s phone or through another method.

While MotionDSP’s advanced software and video capabilities can be used to help drones perform their tasks in a variety of critical applications, another one it’s partially well suited for is search and rescue. Typically search and rescue missions can only be done during the day, Varah said, but drones can fly at night. And a drone equipped with the right video will have much better luck locating a missing person.

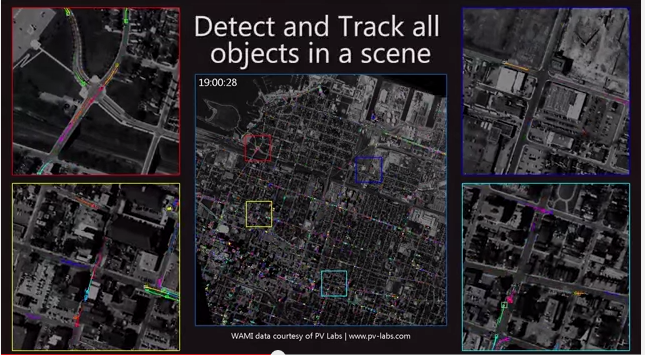

“You can send a drone and use our software to detect motion or detect when areas of heat show up on an image,” Varah said. “It really augments the human search team because the algorithms can detect things the human eye can’t. The human eye can only look at one area of the screen while we can look at all areas of the screen all the time.”

Making the Transition from Military

As MotionDSP transitions from focusing mainly on the military market to consumer applications, there are a few challenges they’ll need to overcome.

For instance, the military has the capability to train and put multiple people on a single mission, Varah said. A single Reaper or Predator drone involves 75 people working on one aircraft and on one video feed. When you’re talking about farmers, they certainly don’t have that type of manpower, and that means making the software more sophisticated and easier to use.

“The military can take people and train them for two years to become an expert in video analysis. A farmer doesn’t have time to do that,” Varah said. “The two big challenges are you have to bring the price point down, but at the same time you have to make the software more sophisticated because it has to be automated, and reliable in a way that the military doesn’t need because they can put people on it.”

The Partnerships

Varah is excited to be working with the universities and said doing this type of research is key to coming up with solutions that work.

“To build a solution for search and rescue or a solution that looks for missing cattle or that scans a gas pipeline for damage sounds simple to describe, but to make something that works seven days a week in any kind of environment or any kind of weather entails several tests to make sure it works,” Varah said. “The universities can do that testing, so because of that we can look at real information, real data.”

Varah also likes the idea of working with young under graduate and graduate students because they bring a different perspective to the research. These smart 18 to 30 year olds always have fantastic ideas, he said, and often point out things he’s never even thought of. These outside perspectives will only help improve the solutions and ultimately solve the problems these various industries face.

And that’s really what the evolving drone industry and the related emerging technologies are all about.

“It’s about answering questions,” Varah said. “A farmer won’t buy a drone unless it does something for him. We need to figure out how we use sophisticated computers and software and drones to answer these important questions. It could be a farmer saying where is that really expensive bull, or rescuers asking where is that lost hiker. These are all data questions, and that’s where drones get really, really interesting. Solving problems and answering questions.”