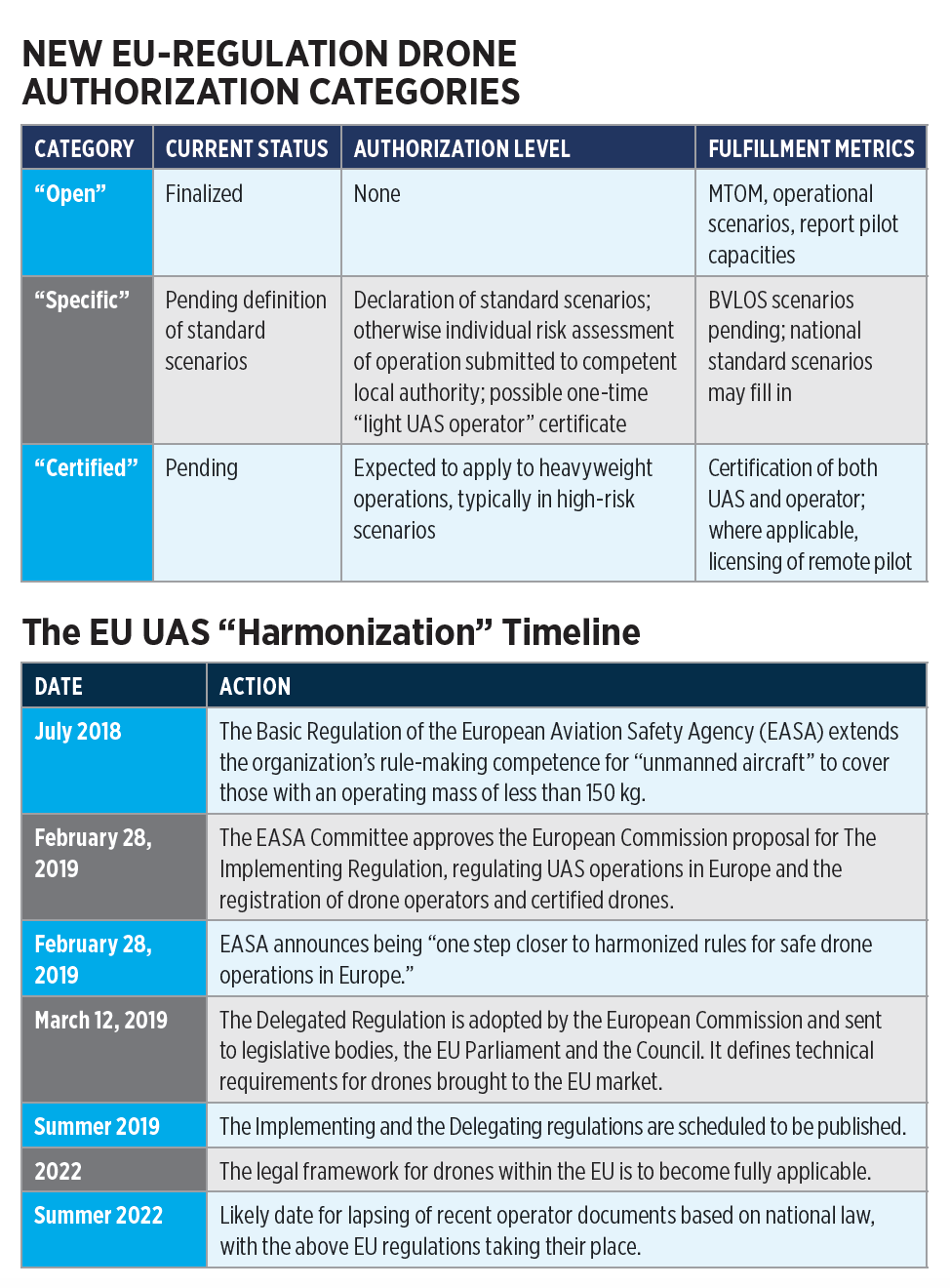

The EU published a new set of UAS regulations as recently as June 11, 2019. What does the operations-centric and risk-based approach mean for UAS operators and remote pilots in practice?

If an operator already has a drone, he should look out for the drone’s class identification label. Such labelling shows that the drone may be used in the least restrictive—“open”—of the three authorization categories (see Table on page xx) without prior authorization and, depending on the class number, also helps to determine the subcategory it may be operated under. If the drone has no such identification label, possibly because it was acquired before the Regulation was applicable, the UAS operator should be able to determine the class himself by applying the drone’s technical specifications—at least within the applicable transmission periods.

Following the classification, the characteristics of the intended operation have to be determined and assessed as to whether they stay within the limitations of the applicable “open” (sub-) category. The competency requirements of the remote pilot range from mere familiarization with the user’s manual of the UAS, to additional theoretical training and online examinations, to holding a certificate of remote pilot competency issued by the competent authority or by a recognized entity.

ACROSS BORDERS, BEYOND REGISTRATION STATES

No additional authorization is required for operations subject to the “open” category. So, one would expect cross-border operations within the EU not to require authorizations either. When focussing on air law, the main question is then whether the proof of competency obtained by the remote pilot in one Member State is recognized in the Member State of operations. Remote pilots that exceptionally benefit from a lowered minimum age are only then restricted to operations in this specific Member State. This suggests a concept of mutual recognition in general. However, it does not excuse the remote pilot from familiarization with the local geographical and also legal requirements beyond air law. In practice, this aspect may still be a limiting factor for cross-border operations.

For operations subject to the “specific” category, the other EU Member State is required to assess the operational authorization already granted by the Member State of registration to the UAS operator and report back on the adequacy of risk mitigation measures for the intended location. Here, the UAS operator requires prior confirmation by the other Member State. The regulations suggest that such confirmation may only be refused if the mitigation measures contained in the authorization are not satisfactory or have not been updated for the intended location.

For operations subject to the “specific” category, the other EU Member State is required to assess the operational authorization already granted by the Member State of registration to the UAS operator and report back on the adequacy of risk mitigation measures for the intended location. Here, the UAS operator requires prior confirmation by the other Member State. The regulations suggest that such confirmation may only be refused if the mitigation measures contained in the authorization are not satisfactory or have not been updated for the intended location.

Unfortunately, there is little guidance if and, in case, on what grounds a recognition of an existing authorization can be rejected and, in that case, how such rejection may be challenged. It is difficult to conceive that a Member State would recognize any authorization by another Member State unless based on a standard scenario given that also all operationally relevant national laws have to be considered. However, if the intended operation is in line with a standard scenario, a mere declaration of compliance by the UAS operator is sufficient anyhow.

THIRD-COUNTRY OPERATORS

Aside from intra-European drone operations, UAS operators from third countries may be interested in using their drones within the EU. For such cases, the competent authority shall be the one of the first Member State where the UAS operator intends to operate. The authority may recognize existing certificates on remote pilot competency for operations within, to and out of the Union.

…THERE ARE A NUMBER OF ISSUES THAT STILL NEED TO BE SUCCESSFULLY RESOLVED FOR A “MISSION ACCOMPLISHED” VERDICT.

THE “LIGHT UAS OPERATOR CERTIFICATE”—“LUC”

The newly introduced “light UAS operator certificate”—“LUC”—provides a convenient method for UAS operators to obtain a general authorization for operation scenarios under the “specific” category, which otherwise would be subject to individual authorizations. The LUC requires the presentation and upholding of a detailed management and organization structure within an undertaking, which needs to be precisely described in a LUC manual made available to all relevant personnel.

CONTINUED VALIDITY OF EXISTING LICENSES

Many undertakings have already obtained licenses under the currently applicable rules of

EU Member State laws for professional UAS operations. It is therefore important for them to know how far these licenses will remain valid once the new EU regulations apply.

Authorizations granted to UAS operators, certificates of remote pilot competency and declarations made by UAS operators or equivalent documentation, issued on the basis of national law, shall remain valid until July 1, 2021, and Member States are to convert the existing documents in due time. The transition period for operations conducted in the framework of model aircraft clubs and associations runs one year longer and will lapse at the end of June 2022. Since any conversion has to follow the requirements of the Implementing Regulation, only those national authorizations and declarations can be expected to survive beyond the applicable periods that already comply with the new rules. Otherwise, additional requirements would have to be fulfilled or the authorization or license will need to be fully renewed.

CONTINUED PERMISSION TO USE EXISTING UAS

The requirements for classifications of UAS will directly be applicable in the Member States without providing for a transition period. This means all UAS brought on the market after July 1, 2019, will already have to comply with these requirements. Anyone buying a drone after that date should therefore make sure that he is not sold recent stock but a model already compliant with the new Regulation.

“ …this Regulation is without prejudice to the possibility for Member States to lay down national rules to make subject to certain conditions the operations of unmanned aircraft for reasons falling outside the scope of Regulation (EU) 2018/1139, including public security or protection of privacy and personal data in accordance with the Union law.”

However, there are transitional provisions for continued operation of “old” drones for the benefit of UAS operators. Companies that are still operating UAS not in compliance with the new requirements will want to know if the operation may be continued. The question only arises for “open” category operations, since operations in all other categories will be subject to specific authorizations requirements, anyhow. Non-compliant UAS types placed on the market before July 1, 2022, will be allowed to continue “less risky” operations, either in subcategory A1 and MTOM less than 250 g or in subcategory A3 (far from people) with MTOM less than 25 kg.

HARMONIZATION ACHIEVED?

The development of harmonized rules on UAS in the EU has not reached the finish line yet, and there are a number of issues that still need to be successfully resolved for a “mission accomplished” verdict. The main risk to harmonization stems from the caveat for national deviations.

In particular, the definition of UAS geographical zones for safety, security, privacy or environmental reasons is left up to the Member States, which may prohibit certain or all operations, or make them subject to specified conditions, standards, classes or use of equipment such as remote identification systems or geo awareness systems. Furthermore, many elements, such as the content of remote pilot competency requirements and the standards for the electronic registers to be created by Member States have yet to be defined. The complexity of these tasks should not be underestimated, not to mention the still-not-published standard scenarios that will form the backbone for efficiency when applying the “specific” category. It is therefore not surprising that comments of industry stakeholders published on the Commission website support the overall aim of harmonization but also warn of national particularism that may yet contravene the effort.

It therefore remains to be seen how the quite significant “white spots” in the framework of EU UAS regulations will be filled in the coming months. At that point, it will be worth revisiting the topic.