Making deliveries from shore and at sea could make operations more efficient for the Navy at sea and Marine Corps Warfighters on land.

Consumers aren’t the only ones eagerly awaiting the ability to have packages delivered by drone—the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps are as well, and are actively working to make that day a reality.

The Navy has several projects under way to demonstrate ship-to-shore and ship-to-ship drone delivery, some of which will primarily be operated by the Marine Corps. Similar efforts are also taking place within the U.S. Coast Guard’s Research and Development Center, Defense Innovation Unit and DARPA.

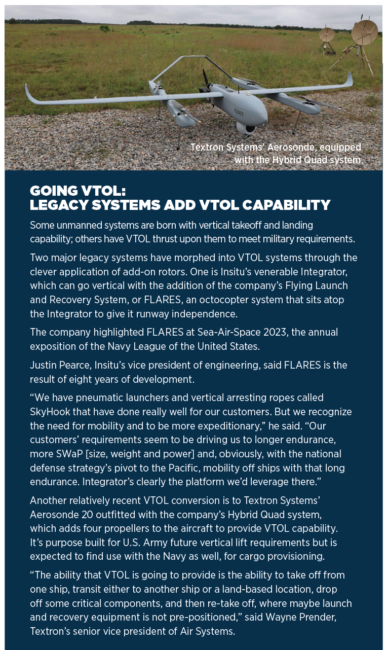

Industry is also taking note, as vertical takeoff and landing has become the name of the game, with even traditional fixed-wing aircraft adding VTOL capability. Why VTOL? For ships, space is at a premium, so not requiring large decks or recovery devices is a plus.

“We want to operate off of any type of ship,” Marine Corps Col. Victor Argobright, program manager for the Navy and Marine Corps Small Tactical Unmanned Aircraft Systems program office (PMA-263), told Inside Unmanned Systems. Larger ships have room for non-vertical takeoffs, but for destroyers, Military Sealift Command vessels or smaller ships, “the only way to get this type of capability on and off is to have that VTOL-type capability.”

Christopher Heagney, the Naval Air Fleet and Force advisor to U.S. Naval Forces Southern Command/U.S. 4th Fleet and ONR, agreed in an email interview. “VTOL offers significantly less footprint,” he wrote. “Logistics delivery doesn’t inherently require VTOL [i.e. Zipline], however, a smaller UAS footprint enables operation from more ships or expeditionary locations.”

Argobright said VTOL is also helpful for land deliveries, such as to hidden Marines. “You want the systems to be able to land in a pretty tight spot.”

DARPA, SIKORSKY DEMONSTRATE AUTONOMOUS LOGISTICS

The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps aren’t the only services interested in using unmanned systems for delivery, as DARPA and Lockheed Martin subsidiary Sikorsky showed the U.S. Army last fall that an optionally piloted Black Hawk helicopter could deliver supplies or carry casualties.

As part of the Army-led Project Convergence 2022, Sikorsky and DARPA conducted three demonstration flights at Yuma Proving Ground, Arizona, with both human pilots and Sikorsky’s MATRIX autonomy system, which combines onboard software and sensors and can be installed on a variety of aircraft.

During one sortie, the aircraft flew as low as 200 feet above ground as a terrain-masking exercise, moving at 100 knots. In another, a ground operator with a secure radio and tablet took control of the unmanned helicopter, commanding it to release its sling load, and then land to evacuate a mock casualty (a mannequin) from a nearby location.

“Our MATRIX technology gave the U.S. Army considerable insight as to how its existing Black Hawk utility helicopter fleet could evade threats on a future contested battlefield,” said Igor Cherepinsky, director of Sikorsky Innovations. “MATRIX is a demonstrated solution that’s ready to be transitioned to the Army whenever they choose to modernize the enduring helicopter fleet, or acquire next generation aircraft.”

In March, Sikorsky announced its collaboration with GE Aerospace to produce a Hybrid-Electric Demonstrator (HEX), a fully-autonomous hybrid-electric vertical-take-off-and-landing prototype.

The company is also working with NASA’s Advanced Air Mobility National Campaign to advance autonomy software and hardware for future advanced air mobility flights, including cargo delivery.

BLUE WATER, TRUAS, MARV-EL

Argobright’s PMA-263 has three unmanned logistics efforts, two intended for the Marine Corps, one mostly for the Navy. The Navy program is the Blue Water UAS effort, which began as a collaboration with Military Sealift Command.

The Blue Water UAS is intended to carry payloads of up to 50 pounds at distances of up to 250 miles. According to a Military Sealift Command study, about 95% of their critical parts weigh 50 pounds or less, so the Navy wanted to see what capability exists “that could deliver a small part a long distance,” Argobright said. Prototypes recently evaluated to participate in upcoming exercises included Shield AI’s V-BAT 128 and a Skyways V2.6b.

The effort is now in what he called the “experimentation exercise phase” to develop the concepts of operation.

“We’re now transitioning to putting this capability in real exercise experiments,” including a Fleet Battle Problem off the coast of North Carolina next month, then another exercise in the early fall, he said.

The North Carolina exercise isn’t solely devoted to drone delivery, but it’s a component, and the Blue Water prototypes will deliver parts “from ship to ship, or ship to shore, over a number of days…it’s really an opportunity for the Navy to learn how they are going to integrate this type of capability into normal operations.”

The Marine Corps-focused systems are the TRUAS, which stands for Tactical Resupply UAS, and MARV-EL. TRUAS is intended to carry heavier payloads than the Blue Water UAS, up to 120 pounds, but for a range of about 7.5 miles.

“Right now, it is land based, but there is an increment later on that we’re working to make that a ship-based type capability,” Argobright said.

MARV-EL, which stands for Medium Aerial Resupply Vehicle—Expeditionary Logistics, is the former Medium Unmanned Logistics System—Air, or MULS-A. MARV-EL, Argobright said, is just a catchier name.

MARV-EL could carry payloads weighing 300 to 600 pounds a distance of 100 miles. “There’s an objective requirement for it to be ship-based,” he said. A heavy payload could be put on MARV-EL, sent to a forward location, then distributed further with TRUAS.

Of all the systems, TRUAS will be the first fielded. “We awarded a contract to Survice for TRUAS in April,” Argobright said, for 21 of Survice Engineering’s TRV-150c vehicles. “We are expecting initial delivery in late September. Those will be fielded to the Marine Corps in support of our logistics Marines.”

Crucially, TRUAS will be operated by the logistics Marines, the Logistics Combat Element, rather than relying on aviation units, which should make the operations more efficient. A training program has been established and the operators will get a special designation. “They are the ones that are going to be operating it, kind of in support for themselves,” he said.

In the meantime, the USMC will continue working with prototypes it bought from Survice Engineering. Lessons learned from TRUAS will filter to the larger MARV-EL. PMA-263 awarded two Other Transaction Authority awards for MARV-EL in January, to Kaman and Leidos.

“They are each going to build a prototype over 18 months and then we’re going to be doing evaluations of each of those prototypes in the field with marines in early fall of 2024,” Argobright said.

Photos courtesy of the U.S. Marine Corps/Lance Cpl. Kayla LeClaire and the U.S. Navy.

FLEXING

Last October, the Navy’s latest Fleet Experimentation Program (FLEX) was held in waters around Key West, Florida, aboard the USNS Burlington (T-EPS-10), a Spearhead-class expeditionary fast transport vessel, building on work that had begun the previous year.

The effort, organized by U.S. Naval Forces Southern Command/U.S. 4th Fleet, along with the Office of Naval Research’s SCOUT initiative, included demonstrations of drone delivery to aid Joint Interagency Task Force South’s fight against illicit trafficking in the U.S. Southern Command’s area of responsibility.

In the email interview with Inside Unmanned Systems, Heagney wrote there’s much work still to be done.

The 4th Fleet “began an experiment campaign focused on contested logistics in 2021,” he wrote. “Many technical problems need to be solved before logistics UAS are ready for fleet use. Each year builds to tackle the next technical hurdle.”

The FLEX work started in 2021 with an operational problem: Getting rid of the launch and recovery equipment on the sending and receiving ships. Heagney said 4th Fleet used two Volansi UAS, a C10 and M20, to deliver cargo from USNS Burlington to U.S. Coast Guard Cutter William Trump and a surface boat, marking the first autonomous ship-to-ship drone deliveries. (The history-making achievement was not enough to save Volansi; a little over a year later, the company’s assets and intellectual property were bought by Sierra Nevada Corp.)

“Three successful sorties were flown delivering cargo without any control by the receiving vessel,” Heagney wrote. “The UAS flew completely autonomously beyond the datalink range [around 7 nautical miles], delivered the cargo and returned. However, the ships required a transmitting beacon for the UAS to detect the landing location.”

The next operational problem, in 2022: Get rid of the beacon.

Heagney said the 4th Fleet teamed with the DIU and Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory to develop computer vision for intelligent, autonomous navigation. Three UAS—an L3Harris FVR-90, a Skyways V2.6 and and SURVICE Engineering TRV-150—leveraged cameras to land, using deck markings, and to identify the right ship on the horizon.

“We also did USV [unmanned surface vehicle] logistics delivery including a 500 lbs shore-to-ship delivery using a GARC [Greenough Advanced Rescue Craft from Maritime Applied Physics Corp.] to USNS Burlington,” he wrote. “We also used two USVs for shore-to-shore autonomous

logistics deliveries to an expeditionary force on an austere island.”

DRONE DELIVERY BENEFITS

At the time of the FLEX demonstration last fall, Heagney said drone delivery could bolster JIATF-South ships by ferrying repair parts, which could keep the ships on station longer.

Argobright said another benefit is cost. For example, TRUAS isn’t exactly cheap at a bit over $300,000 each, but for a system delivering ammunition or parts, “that’s somewhat attritable,” and very inexpensive compared with a V-22 Osprey or an H-1 helicopter.

“It just really frees up resources, it reduces the risk to the warfighters when you can use an unmanned system to deliver something,” Argobright said.

The Navy’s drone delivery push is driven both by the desire to be more efficient in countering China, and just because it’s a good idea, Argobright said. He’s also keeping an eye on the commercial market, which is seen as being on the cusp of dramatic expansion once regulations are in place.

“I leverage the commercial world. I want the commercial world to go fast, that makes my job easy,” he said, which includes issuing frequent requests for information to industry. “The faster they go, they faster I can go.”

For instance, the TRUAS vehicle is largely a commercial air vehicle based on a vehicle built by the United Kingdom’s Malloy Aeronautics. Survice Engineering buys the systems from Malloy, modifies them for the U.S. military “and that’s what we’re fielding out to the Marines,” Argobright said.