Climate conditions are leading to more wildfires, but drones can help prevent them or keep them at bay.

As temperatures continue to rise, wildland fires have become more frequent and intense around the world. The incendiary combination of hotter temperatures with careless human activity, lightning and sub-optimal land-use practices has ignited a global crisis.

These fires don’t just kill trees. They spur death, negatively affect human wellbeing and result in physical devastation. To stay ahead of this threat, those in charge of mitigating, responding to and aiding in wildfire recovery efforts have turned to unmanned aircraft systems to help them in this critical fight.

A HOT MESS

Today, extreme heat waves continue to dry out the land and set the stage for fires at rates five times greater than 150 years ago. Exceptional incidents in Maui, Canada and Greece represent just a few of the wildfire events that gripped this year’s headlines. In all three cases, climate-related drought conditions created a tinderbox that humans helped ignite. Representative of the larger problem, these fires left behind an unprecedented wake of fatalities, destruction and economic, health and environmental impacts.

The catastrophic fire that ripped across Maui in August decimated the beautiful and historically significant town of Lahaina. The area’s arid drought-related conditions and strong winds fueled the inferno that claimed the lives of 115 people, consumed over 2,000 homes and displaced at least 7,200 people. The resultant ash contained elevated levels of several toxic substances, including arsenic, lead and cobalt.

In Canada, about half of the country’s 798 reported active “out of control” fires (a classification from the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre) raged at some of the fastest recorded rates and produced record breaking amounts of emissions. For months, smoke that originated in Western Canada blanketed the eastern U.S. from thousands of miles away, triggering health warnings that urged people to stay indoors.

Fires also tore through Greece this summer. According to the European Forest Fire Information System, only two months into these incidents, the size of areas burned had already surpassed that of the country’s disastrous 2021 fire season, which ravaged over 130,000 hectares of land and caused extensive damage to homes and infrastructure. These fires produced smoke plumes that choked Athens, the nation’s capital, and stretched hundreds of miles toward Italy.

As illustrated by these incidents, the dangers of wildfires include more than the rapacious nature of the fire element itself. Emissions from these fires include fine particulate matter, small solid particles or liquid droplets (2.5 microns or less in diameter or PM 2.5) that can burrow deep into the lungs. Short-term, this can cause health effects, including eye, nose and throat irritations, coughing, sneezing, runny nose and shortness of breath. Long-term exposure to PM 2.5, however, can compound pre-existing conditions such as heart disease and asthma.

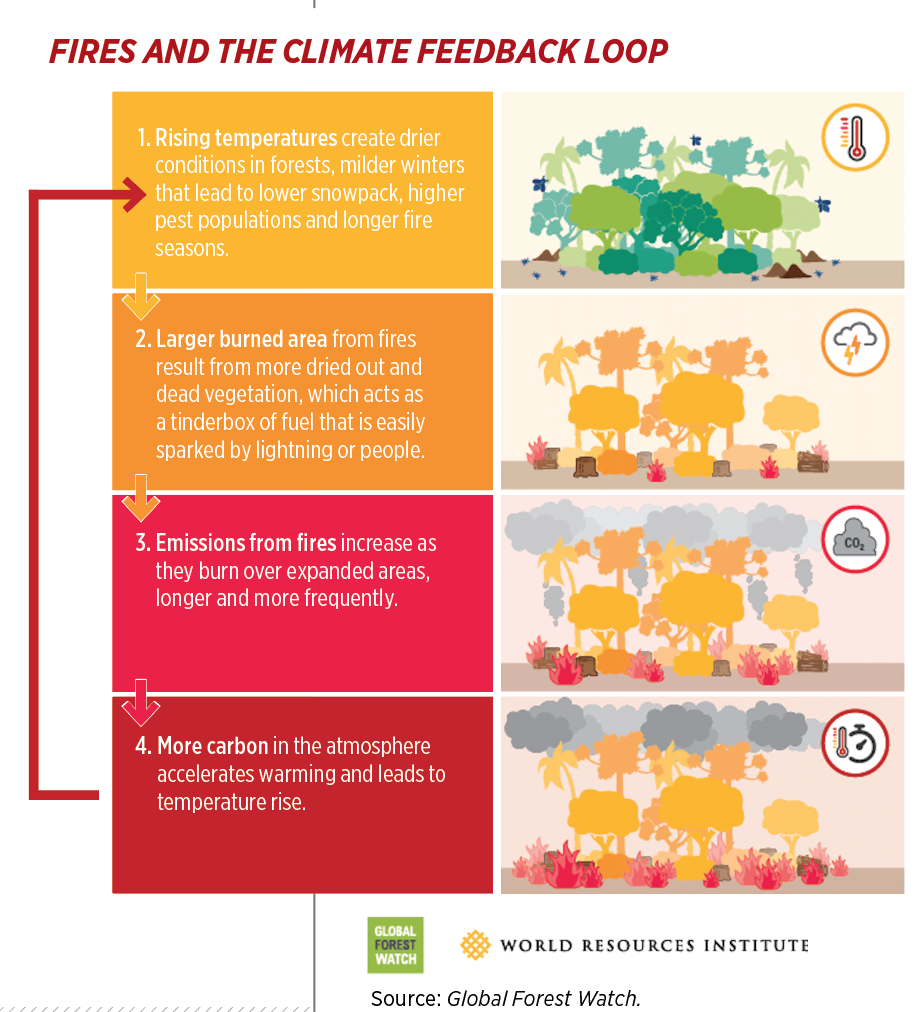

Fire emissions also worsen the environment in a different way. By releasing large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, they create a vicious circle that accelerates climate change, which, in turn, leads to even more fires. To stay ahead of this high-speed curve, public servants have turned to UAS to assist them before, during and after wildfires.

AN OUNCE OF FIRE PREVENTION

The saying “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” applies equally to wildfires. To help prevent fires from starting in the first place, federal, state, local, tribal and territorial agencies use UAS to detect potential problem areas, gather data and take action in advance of a disaster.

Using UAS to map and survey high-risk areas before an incident aids in fire mitigation. UAS equipped with high-resolution, multi-spectral sensors can quickly, effectively and cheaply reach remote areas and cover large swaths of land over long periods of time.

Collecting data on features such as tree density and health, soil conditions, steepness of terrain and natural disturbances (e.g., impacts from wind and weather) allows officials to track forest conditions and identify areas that may be more susceptible to fires. The actionable intelligence gathered from these operations can guide key decisions for land and forest management, including the necessity for controlled burns. Controlled burns, or aerial ignition operations, bolster forest resilience by reducing the buildup of grasses and other vegetation that can increase the chances of wildfires.

Wildfire preparedness includes structural vulnerability assessments in addition to vegetation monitoring, said Jennifer Schmidt, associate professor of natural resource management and policy at the University of Alaska’s Institute of Social and Economic Research. Her team uses drones and digital twins to provide the type of high-quality data needed to conduct these analyses.

Experts in Alaska and elsewhere increasingly use UAS, first to determine if a controlled burn is needed, then to assist with those burns. Using plastic sphere dispensers (PSDs) integrated onto a UAS, fire experts can rapidly drop fireball igniters to start prescribed fires and carefully monitor them. These methods greatly enhance the safety of these operations, which are otherwise conducted on foot in challenging terrain or with a crewed helicopter or fixed wing aircraft flying in high-risk profiles.

“Every seven years we kill a helicopter firefighter,” said Dave Whitmer, director of business operations at Global UAS Solutions. “Anytime you put a helicopter in a low, slow profile, you are putting them in danger. It might cost $80,000 for a drone, but if you crash a helo, the cost doesn’t just include the hardware. It includes two lives.”

The dollar savings also makes sense. The fuel burn comparison is 300 gallons per hour for a helicopter versus 300 grams for a hybrid drone.

These benefits inspired the U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) to create one of the earliest federal, non-military UAS programs in 2009. Every year since, the number of interagency UAS flights has increased. In 2020, various DOI bureaus—the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service and Office of Aircraft Services—had treated approximately 15,500 acres using UAS and PSDs throughout Florida, Texas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Mississippi and Georgia. In its program report, DOI stated UAS “help ensure safe and frequent prescribed burn ignitions by reducing crew fatigue, mitigating concerns over escaped fire, and preventing other hazards.”

For these reasons, among many others, UAS operations have also proven vital during wildfire events.

55 POUNDS OF HIGH-TECH CURE

During a wildfire event, UAS enable first responders to detect small embers at the start, monitor their spread, provide life-saving equipment support and help keep fires contained. After a fire event, UAS assist in recovery efforts, from search and rescue operations to building integrity inspections.

Across the spectrum of an incident, UAS provide unparalleled situational awareness and assessment capabilities for disaster response teams. They can rapidly canvas large areas of land and provide a high-resolution, birds-eye view of developments in real time. UAS equipped with thermal FLIR (forward looking infrared) cameras, which detect infrared radiation emitted from hot objects, can pinpoint hot spots and locate living beings, even in smoky environments.

In Maui, for instance, a Central Coast nonprofit, Assert Drone Animal Rescue, used UAS equipped with IR sensors to help rescue lost cats and reunite them with their families. The sensor picked up the animals’ heat signals, pinpointed their exact locations and enabled the Assert team to send in help. In just 30 days, they rescued 26 cats impacted by the toxic burn zone.

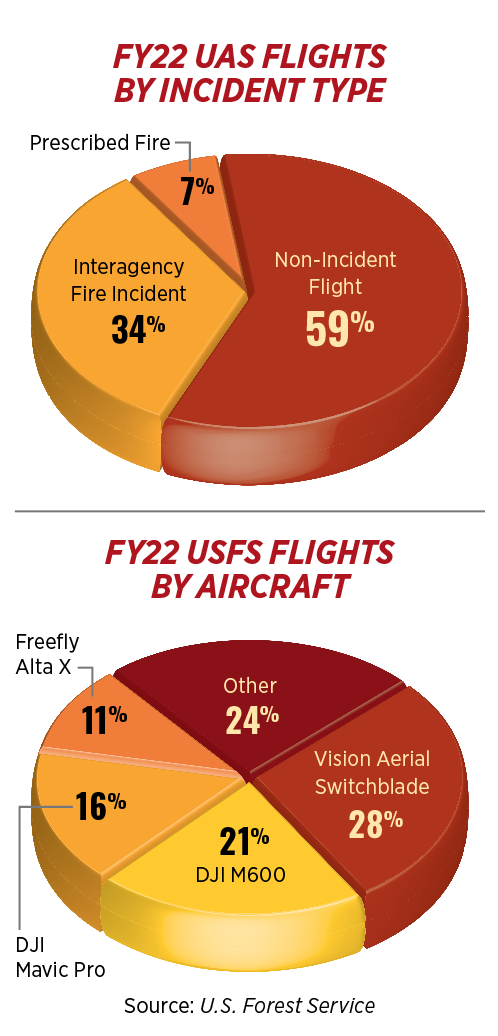

UAS also help to contain fires by spraying fire-retardant chemicals or water and to ignite miles of fire-containing backfires in a short time. The DOI often uses UAS and PSD operations to supplement crewed flights and to supplant traditional aviation efforts at night and in low visibility smoke situations. For example, during Colorado’s third largest wildfire to date, the 2020 Pine Gulch Fire, DOI and BLM night operations involved 161 UAS-PSD flights that dropped over 58,000 fire ignition balls to contain it. In fiscal year 2022, fire incidents topped the agency’s charts at No. 2 for UAS use cases and comprised 30% of all interagency flights.

First responders have also used UAS to help transport critical supplies to the site of a fire, review structural and other damage, locate missing persons and help replant forests and assist in flood mitigation during the recovery phase.

Yet we’ve only just scratched the surface of what UAS can do during fires.

EVEN MORE FIRED UP

Research and development continues at both the federal and state levels to explore how to truly unleash the full power of UAS during wildfire events. One of the major limiting factors for widespread adoption of UAS technologies in wildland firefighting is a lack of situational awareness tools for responders to see where firefighting drones are operating.

To address this problem, NASA just launched the Advanced Capabilities for Emergency Response Operations (ACERO) project. Led by the agency’s Ames Research Center, the project seeks to use UAS and advanced aviation technologies to enable 24/7 wildland fire operations. The project will help hone wildfire fighting concepts of operations and otherwise knock down barriers to adoption by perfecting UAS-PSD operations and testing common situational awareness and airspace management tools for responders.

As part of ACERO, NASA researchers recently tested a mobile air traffic management (ATM) kit for remote ground pilots across forests throughout Tennessee, Mississippi, Georgia, Florida and South Carolina. NASA researchers tested their ATM kit during U.S. Forest Service and National Interagency Prescribed Fire Training Center pilot training for UAS-PSD operations in all five states. The kit alerted pilots positioned in forests to air traffic detected in the surrounding area. This enhanced their ability to avoid conflicts while conducting prescribed burns.

“It was a successful data collection exercise,” said Lynne Martin, lead of ACERO’s Wildfire Airspace Management team at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. “We demonstrated the kit to 24 trainees and eight instructors and obtained feedback from all.” NASA will now analyze the data and prepare the ATM kit for mainstream adoption.

Even before ACERO, some states had launched their own firefighting R&D efforts. Notable among these, Colorado’s Center of Excellence for Advanced Technology Aerial Firefighting (COE) within the State of Colorado Public Safety Department’s Division of Fire Prevention and Control, has been on the cutting edge of incorporating advanced tech solutions in wildland firefighting efforts for years.

Led by Director Ben Miller, a self-proclaimed “pragmatic technologist” who, in his former position with the Mesa County Sheriff’s Office, was the first in the country to start a public safety UAS program in the 2008-2009 timeframe, the center focuses on moving public safety toward the state of the art for aerial firefighting. To do this, the COE team conducts critical firefighting R&D and operational testing. It also provides training, certifications and operational assistance.

As one of its many projects, the COE launched the Colorado Team Awareness Kit (COTAK) last year. Developed using the U.S. Department of Defense’s Team Awareness Kit (TAK), which provides situational awareness to military forces, the TAK app pushes out up-to-the-second location services to all Colorado first responders for free. The R&D for this project, before its operational implementation, started in 2016.

“Wildland fire management is increasingly relying upon technology to support decisions and increase situational awareness,” Miller said.

Based on the TAK program’s success, the COE landed a five-year, $1.6 million agreement with the Forest Service to, among other things, broaden adoption of Wildland Fire Team Awareness Kit (WFTAK) smartphone apps and build out other capabilities to support public safety responders and wildland firefighters. WFTAK provides almost real-time location tracking and mapping capabilities to firefighters, as well as cutting edge connectivity solutions and integrations of sensors and cameras for use by firefighters.

These are but a few examples of how UAS, and related technologies, continue to evolve along with the ever-worsening wildland fire environment.

UAS KEEP COMING IN HOT

The National Interagency Fire Center’s National Significant Wildland Fire Potential Outlook for the period November 2023 through February 2024 projected “above normal significant fire potential” across Hawaii, Louisiana, much of Mississippi and all of Alabama during November. This higher risk continues in Hawaii through February. Incredibly, many areas in the U.S. appear to have “normal significant fire potential” during this same period.

As significant wildfire risk becomes the norm, advanced technologies such as UAS can help mankind keep pace. UAS can help mitigate the chances of a wildfire from occurring. When it does, first responders can use unmanned aircraft across a wide variety of use cases to assist in response and recovery efforts. Across the full range of use cases, UAS can provide high-quality, real-time data, or otherwise act as an extension of the responder, in a safer, more efficient and effective manner than traditional methods.

With improved CONOPS, ATM capabilities and further advancements in sensors and other enabling technologies, UAS will keep coming in hot to help protect first responders and the public alike in wildfire emergencies.