With seamless transitions from air to underwater and back, SubUAS’s Naviator platform offers a radically flexible architecture for defense, industrial inspection and environmental intelligence.

In the expanding realm of unmanned systems, few platforms rewrite the rulebook the way SubUAS’s Naviator does. More than a novel piece of engineering, it represents a shift in how to think about autonomy across domains. With its ability to operate in the air and underwater without mechanical reconfiguration, the Naviator offers a truly dual-medium solution—taking off vertically like a drone, diving like a submersible, and surfacing once more.

Owing to this unique design and forward-looking approach, the Naviator earned this year’s Inside Unmanned Systems Innovation Vanguard Award in the Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV) category.

ORIGINS

Founded in 2016 by Rutgers University professors Dr. F. Javier Diez and Dr. Marco Maia, SubUAS emerged from academic research into dual-domain robotics. Diez, a mechanical and aerospace engineer, led early development of the Naviator concept within Rutgers’ applied fluid dynamics laboratory, securing early SBIR and STTR funding to commercialize the platform. The founders’ background in both academia and naval research set the stage for an unmanned vehicle with real-world applications across defense and critical infrastructure.

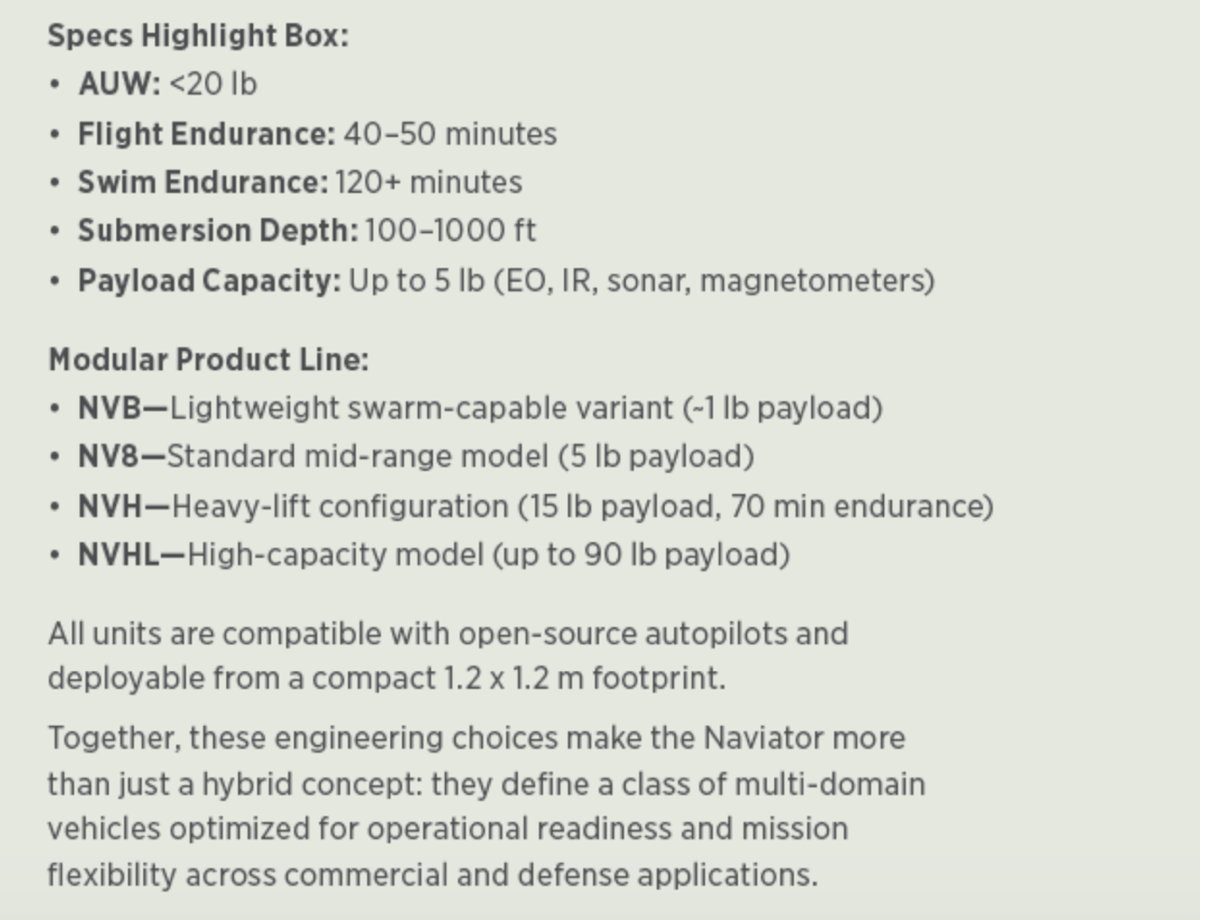

SubUAS has spent nearly a decade refining the design. The Naviator’s ability to transition seamlessly between aerial and submerged operations comes to life through a structurally optimized multirotor airframe and a dual-medium propulsion system to provide VTOL flight and six-degree-of-freedom control underwater. The propulsion system provides lift in air and thrust underwater, eliminating the need for any mechanical reconfiguration.

SURFACE STEALTH AND LITTORAL SURVEILLANCE

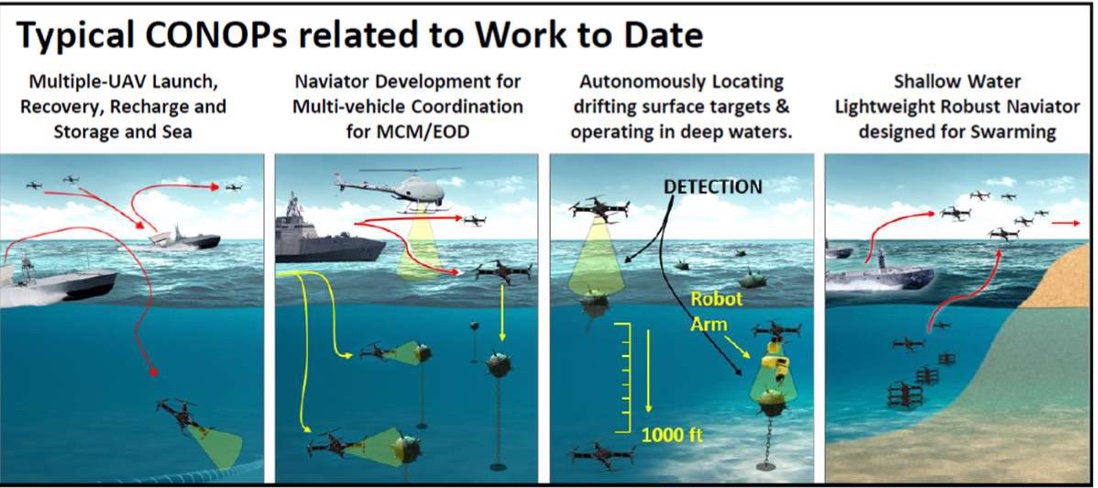

According to the SubUAS team, the platform’s ability to remain afloat in a passive “buoy mode” has implications beyond novelty. In an interview, they explained, “People don’t realize how powerful it is to just stay on the surface. A boat goes by and can’t see it. It’s there, but invisible from the horizon.”

They described potential border security and drug interdiction missions where multiple Naviators could be deployed miles apart, quietly monitoring traffic for hours at a time: “You may think the coast is clear, but it’s not.”

The team emphasized that in some coastal scenarios, the presence of Naviators would be difficult to detect even by experienced traffickers.

DUAL-USE ARCHITECTURE

SubUAS is marketing the Naviator to both defense and commercial sectors. For defense users, the platform supports electro-optical payloads, acoustic sensors, and speculative kinetic capabilities. In concept-of-operations discussions, the team suggested the Naviator could potentially latch onto a suspect vessel or mark it for tracking. “Isn’t that what ISR is all about?”

On the commercial side, oil and gas inspections represent a natural entry point. “They already spend so much time and money mobilizing crews and boats,” one founder said. “Why not send something quick, autonomous and capable of both surface and subsurface inspection?”

They cited underwater pipeline inspection and bathymetric mapping as key early use cases. The platform has already demonstrated integration with multibeam sonar and water quality sensors. “Just give them that freedom,” Diez said. “Once they get their hands on this, they’re going to say, ‘Why am I doing this the old way?’”

DESIGNING FOR AUTONOMY FROM DAY ONE

Unlike many UAV firms with roots in manual piloting, SubUAS’s engineering foundation is in autonomy.“We come from the autonomy community,” they said. “Especially underwater, you can’t rely on joystick control.” The Naviator was built with AI-guided flight, fail-safe protocols, and the ability to complete inspection routes without human input.

This includes precise underwater navigation, object classification, and the capacity to operate in GNSS-denied environments. The team emphasized that SubUAS prioritized building a system that did not require skilled pilots or remote operators in the loop. “Autonomy is not a bolt-on for us,” Diez said. “It’s the DNA of the platform.”

The system is also being positioned as a smart sensor platform—one that could eventually integrate with future generations of expendable or semi-expendable smart mines, distributed sensor networks, or mobile sonobuoy systems. They noted that current drifting sonar systems are vulnerable to current and noise. “Imagine a sonobuoy that doesn’t drift. That’s what we offer.”

CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND THE AUTONOMY WALL

SubUAS has demonstrated the Naviator’s potential to transform inspection workflows by removing the human from the loop. “Right now, inspections might happen once a year,” they said. “But with a platform like ours, you could run them quarterly, or even monthly.”

This is particularly relevant in the context of long linear inspections, such as those required for pipelines, underwater cables, or offshore wind farms. The founders believe these industries are ripe for disruption, particularly as BVLOS regulations expand. “The industry will be divided by who makes it over the autonomy wall—and who doesn’t.”

The platform’s design emphasizes resilience and flexibility in real-world operating conditions. For instance, the team described SubUAS’s proprietary drawing box—a recovery solution that works without fiducial markers, enabling rapid landing on ships in high seas. “You don’t get 30 seconds to land when the ship is pitching,” they said. “You make it quick or you miss.”

MARITIME SECURITY AND PERSISTENT PRESENCE

The team also discussed scenarios where the Naviator could provide persistent surveillance in contested or sensitive waters. For instance, multiple units could be deployed to monitor a maritime border, either passively or with remote sensors that cue action from larger response assets. “Sometimes the most powerful thing is just being there—quietly watching,” they said.

They added that smart mine concepts are increasingly gaining attention among military users. “You can create a field—don’t cross, or else. But when it’s over, you send them home.”

STRATEGIC PATHWAYS AND NEXT STEPS

While defense remains a near-term focus, the founders believe the broader commercial opportunity will unfold over time. “Critical infrastructure needs autonomy,” they said. “This is the future: inspection without pilots, without delays, without costs that spiral.”

SubUAS is currently exploring partnerships to expand its reach into the commercial energy and environmental sectors. The company is also considering licensing options and modular offerings that would allow customers to tailor the Naviator to their own CONOPS without taking on full development risk.

They concluded that it’s not about replacing everything at once. “You start with something small—maybe a short inspection mission that’s expensive with current methods—and you show them a better way.”