Zing Drone Delivery carries hot beignets over the Mississippi River, in New Orleans.

Starbucks coffees, groceries and beignets already fly over neighborhoods near you. Next up: Uber-like VTOL taxis to ferry passengers around and between cities. As the United States expands drone operations, the issue of avigation (aviation + navigation) rights in low-level airspace has popped up.

Who owns the sky, anyway?

AIR RIGHTS ARE A THING

United States v. Causby solidified the concept of “air rights” in 1946. The short version: loud, noisy war planes buzzing less than 100 feet above the Causby farm caused their chickens to go crazy and die. The landowners brought a civil case seeking just federal indemnification under the 5th Amendment “takings clause,” which prohibits the government from taking private property “for public use, without just compensation.” In finding for the Causbys, the Supreme Court of the U.S. (SCOTUS) stated, “if the landowner is to have full enjoyment of the land, he must have exclusive control of the immediate reaches of the enveloping atmosphere.” Here, the flights over the Causby’s farm directly and immediately interfered “with the enjoyment and use of the land.”

Twenty years later, Griggs v. Allegheny County solidified the concept of “air easements,” payments to landowners to use rights of way in the air above their property. Also involving aircraft noise generated over a private home near an airport, the SCOTUS found that navigable airspace does not include “airspace at lower altitudes necessary for the landing or taking off of aircraft, i.e., the path of glide for an aircraft’s take-off or landing” (read: private folks “own” that space).

BACK TO BASICS

Fifth Amendment takings can occur by federal physical actions (e.g., flights) as well as by government regulation (note: the 14th Amendment applies the Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments, to the States). Professor Troy R. Rule, a widely cited aviation law expert, in “Airspace and the Takings Clause,” has called government regulations that impact airspace for the government’s benefit, “veiled airspace easement regulations” requiring payment.

Also in play, the 10th Amendment codifies the broad powers of the individual State to provide for the welfare of its citizens. These state powers, referred to as “police powers,” include, among other things, the authority to regulate property (e.g., trespass, nuisance, zoning) privacy and crime. For this reason, in determining whether a taking occurred, the SCOTUS looked to the law of North Carolina, where the Causby family lived.

And then there’s the Supremacy Clause, which states that federal laws “shall be the supreme Law of the Land.” This forms the basis for federal preemption, the concept that State laws that impede, burden or contradict legitimate federal laws on the same issue will be considered invalid.

STATE OF THE STATES

Still, in the past year, several states, including Texas, Mississippi, Louisiana, West Virginia and New Mexico, put forward bills to either create “toll roads” in the sky or otherwise govern drones in low-level airspace. This May, the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) announced that its intervention had resulted in all these bills being sidelined. In its release, AUVSI stated, “A patchwork of 50 states with 50 different sets of rules would be a disaster for industry.”

That said, according to the National Conference of State Legislators, as many as 44 states have already enacted drone laws. States promulgated the majority of these between 2013 and 2017, mostly to prohibit the police from using drones to collect evidence without a warrant. In the midst of this state-level drone law explosion, in 2015, the FAA’s Office of the General Counsel (OGC) issued a statement on preemption. The OGC recommended that States consult with the FAA prior to initiating “operational UAS restrictions on flight altitude, flight paths; operational bans; any regulation of the navigable airspace” or state mandates for equipment and training.”

With these issues unsettled, in May the Commercial Drone Alliance (CDA) reached out to the White House, requesting a “drone summit” to develop “a comprehensive regulatory regime and technological platform to support expanded UAS operations and their integration into the NAS (national airspace system).”

Causey Aviation Unmanned operates the Flytrex air delivery system to deliver Starbucks directly to customers’ homes.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

The CDA used the term “national airspace system” (NAS) in its recent memo. Interestingly, Congress has not defined that term despite injecting it into the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012. In its non-binding Pilot/Controller Glossary, the FAA defines NAS as a “network” consisting of “U.S. airspace” [another undefined term], aviation-related facilities, rules, technical information, manpower and material.”

Contrast this with “navigable airspace,” which Congress initially defined in the Air Commerce Act of 1926 as “airspace above the minimum safe altitudes of flight prescribed by the Secretary of Commerce.” Congress later updated the term in the 1958 Federal Aviation Act (FAAct), which created the FAA, to include the airspace needed for safe takeoffs and landings. Current regulations define navigable airspace as, “airspace above the minimum altitudes of flight prescribed by regulations…including airspace needed to ensure safety in the takeoff and landing of aircraft.” This matters because, according to the FAAct, the FAA has jurisdiction over the navigable airspace.

But based on its ability to govern the NAS, the FAA has asserted that it has the authority to regulate airspace down to the grass. At the same time, the agency has also tacitly acknowledged private air rights in its requirement that airports purchase air easements before receiving FAA grant money under the Airport Improvement Program (AIP).

Senator Mike Lee (R-Utah) would redefine the term “navigable airspace” to exclude the “immediate reaches of airspace,” defined as “any area within 200 feet AGL [above ground level].” His Drone Integration and Zoning Act of 2021, a recycle of a similar bill introduced in the 116th Congress, would carve out drone sky lanes where the States would govern 0-200 feet AGL, and the FAA, 200-400 feet AGL, for “authorized commercial routes.” Other previous bi-partisan bills on this topic, such as HR 2930 sponsored in the 115th Congress, have not succeeded.

So, where are the boundaries between federal, state and private landowner authority over airspace?

MORE THAN JUST DONUTS AND COFFEE

Neither Causby, Griggs or any case thereafter has defined either the upward limits of private property rights in the air or the top-down limits of the federal government’s regulatory authority.

Other groups have attempted to do this, and quit. The Uniform Law Commission (ULC), which exists solely to provide model acts across diverse subjects for all 50 states to use to enact consistent legislation, abandoned its multi-year attempt at finalizing a “Tort Law Relating to Drones Act” for aerial trespass in 2019.

This is important stuff. And the lines have been drawn. Brent Skoroup, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, advocates for state and local-level avigation easements above public roads. Speaking at an April 2021 Regulatory Transparency Project Podcast hosted by the Federalist Society, he stated, “If states and the federal government don’t collaborate on ‘drone highways’ in the sky, the industry will be constantly fighting trespass and nuisance lawsuits” from private landowners.

Diana Cooper, head of U.S. policy for Genesis Air Mobility, a Hyundai company, disagrees. “Look at the origin story of the FAA. Before 1958, there were two regulators, one for military aircraft and one for civil aircraft. It was disastrous. What happens with 50 or more regulators?” Several high-visibility and fatal aircraft mishaps have resulted from a lack of communication between the FAA’s precursor agencies.

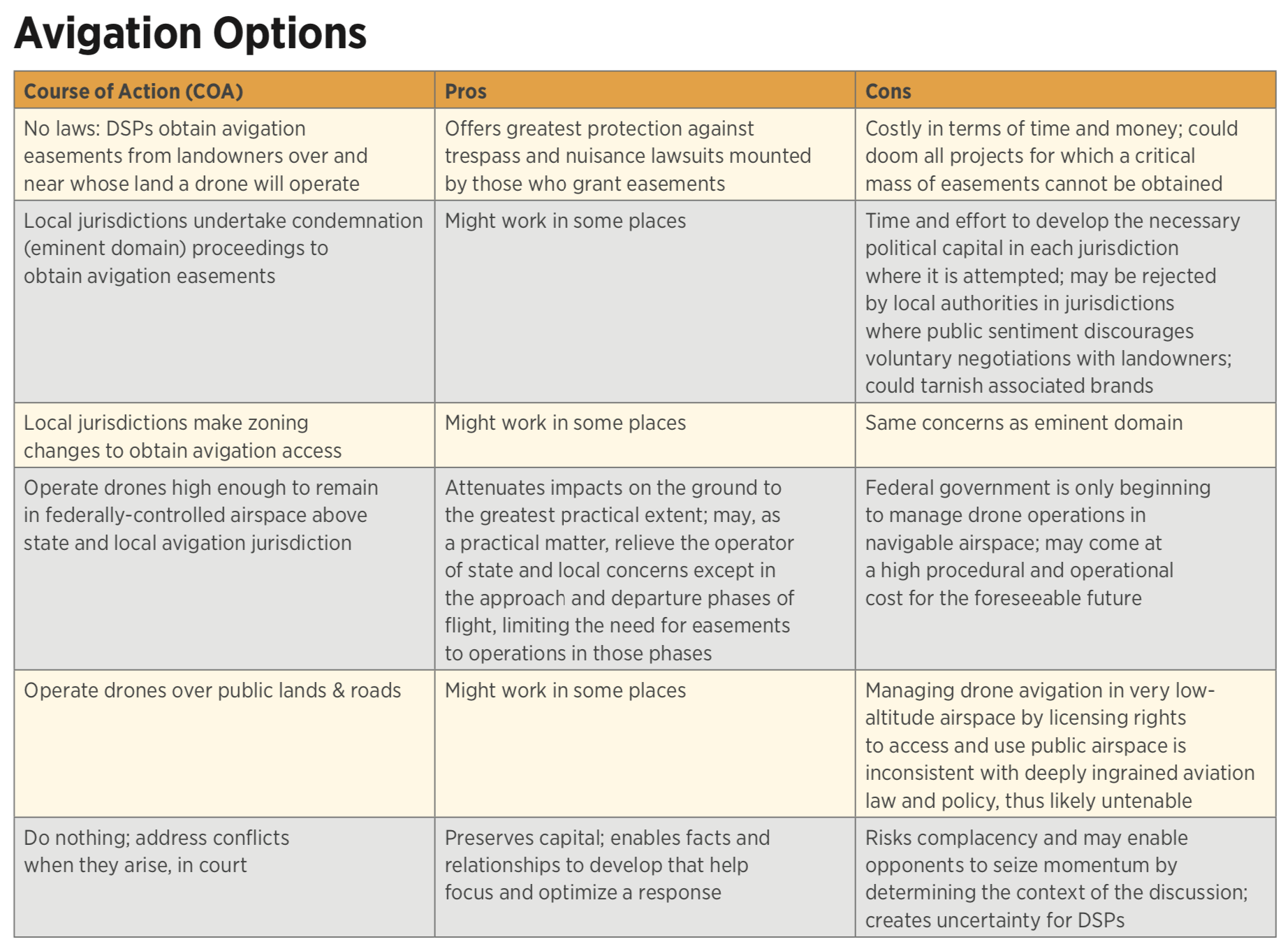

Taking all sides into account, Joseph Corrao, Esq., a civil aviation attorney, former aviation association vice president for regulatory and international affairs and U.S. government regulatory expert, in a discussion at the March 2021 Vertical Flight Society 4th Annual Workshop on eVTOL Infrastructure outlined potential courses of action for avigation, as well as the pros and cons of each (a summary of Corrao’s comments appears in the “Avigation Options” table).

One thing is clear. Air rights, takings and preemption issues in low-level airspace have collided. Whatever the final answer, it will drive the direction of the unmanned aircraft industry. This is no longer about just making, or even delivering, the donuts.