Preflight inspection of the L3Harris FVR-90. RIGHT: The Martin V-BAT, about to tail-sit.

Army solicitations are accelerating the quest to find a mobile, quiet and multi-payload brigade-level successor(s) to the venerable Shadow.

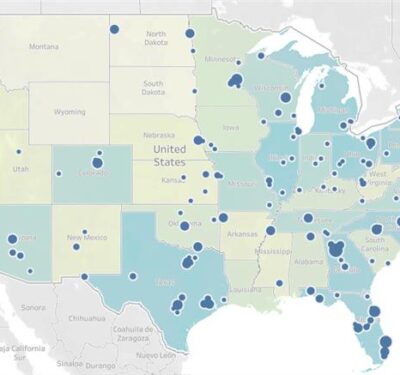

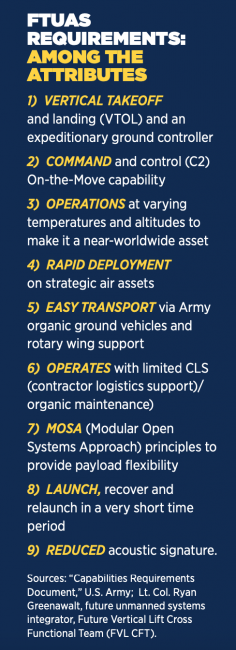

On Sept. 3, the U.S. Army got the attention of the military UAS world when it announced it was soliciting white papers for Increment 1 of its Future Tactical UAS program. Per a two-stage process to find one or more brigade-level successors to the RQ-7 Shadow, the eventually chosen low to medium altitude aircraft would operate as the service’s primary day/night surveillance and target acquisition system. “This requirement is for a fully integrated FTUAS system; not just an air vehicle,” the solicitation declared. The value of this next-generation program has been put as high as $1 billion.

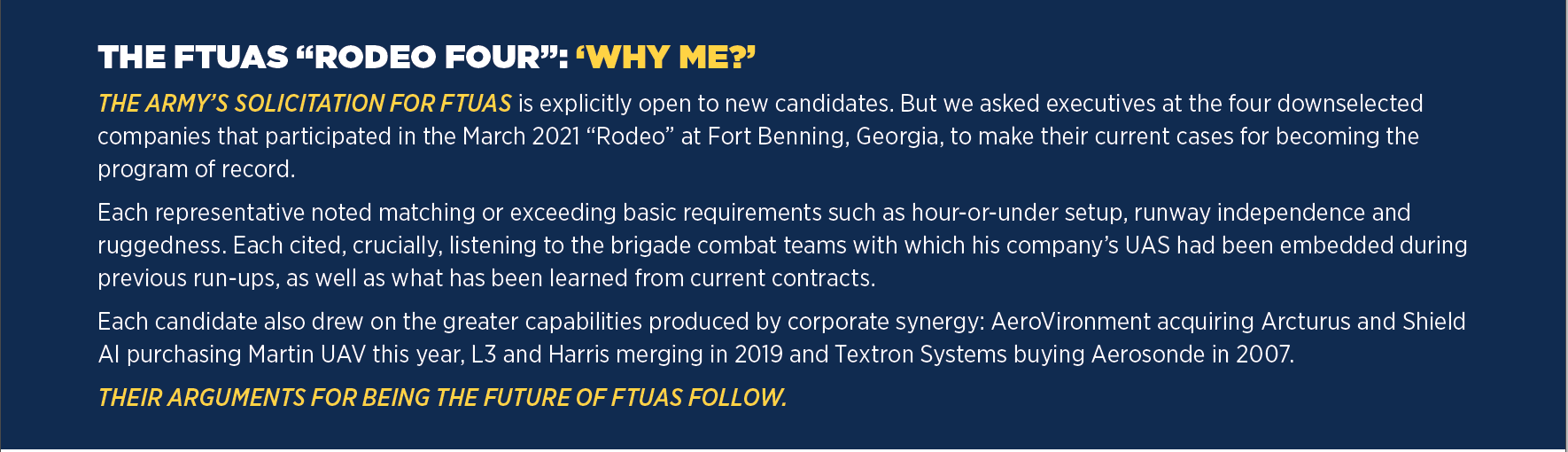

The call for submissions sent potential vendors scrambling: applicants were given two weeks to respond, a deadline later extended to Oct. 2. Respondents would include previous “finalists” that had vied against each other in flyoffs: AeroVironment™ and its JUMP 20®; L3Harris™ with its quadrotor FVR-90; Martin UAV and its V-BAT tail-sitter; and Textron Systems per its Aerosonde™ HQ” (each company makes its case in the sidebars that accompany this article). But Army spokespersons emphasized that this was not to be a closed competition.

Matters accelerated, when, on Sept. 30, the Army released a Request for Prototype for Increment 1, with replies due by the end of October. An additional Increment 2 Request for White Papers was released on Oct. 1.

The search to succeed Shadow within brigade combat teams has contracted and expanded over the past few years. To understand its pulsations, Inside Unmanned Systems sought out Lt. Col. Ryan Greenawalt, the Pennsylvania National Guardsman who is serving as the program’s future unmanned systems integrator. Greenawalt, who works out of the Redstone Arsenal in Alabama, became our wingman, guiding us through FTUAS history, the selection process and the next-generation capabilities being sought. (His additional insights can be found within our MUM-T article package.)

“Increment One will be an initial capability we want to get out to the soldiers as quickly as possible,” Greenawalt explained. “The plan is to get that fielded to a limited number of units in fiscal year ’23.

“Increment Two,” he continued, “is going to be the rapid prototyping effort. It will kind of work in parallel. I’m still not sure how that’s going to work out, but they’re probably going to select three to four vendors and then do a competitive prototyping events starting next year.” Upgrades would follow. “Then, in FYI ’24, they will probably do the actual program of record contract. ’25 will start the program of record fielding.”

Greenawalt’s caution: “I want to be very clear: The selected vendor could be someone outside of those four in the demo.”

The AeroVironment JUMP 20, making a vertical landing.

FROM SHADOW TO NEXT-GEN

Mentions of “quickly” and “rapid” recalled the great physicist Albert Einstein’s theory that time is relative. After all, the various timelines around the quest for the FTUAS have shifted from stately to speedy to somewhere in between. Textron’s TUAS (tactical unmanned aircraft system) Shadow first flew in 1991, and the Shadow 200 became operational in 1999 as the Army’s brigade-level tactical UAS. The Shadow not only met Army requirements for electro-optic/infrared imaging and four-hour, on-station endurance but doubled a call for a 31-mile minimum range. It was also deployed by both the U.S. Marine Corps and other nations. The 7B version appeared in 2004, again more than doubling range, extending official endurance to six hours and offering increased communication capability. Its run continues—introduced in 2020, the Shadow Block III reduced noise and improved communication. The Army ordered new and upgraded Shadow Block IIIs as recently as March 2021.

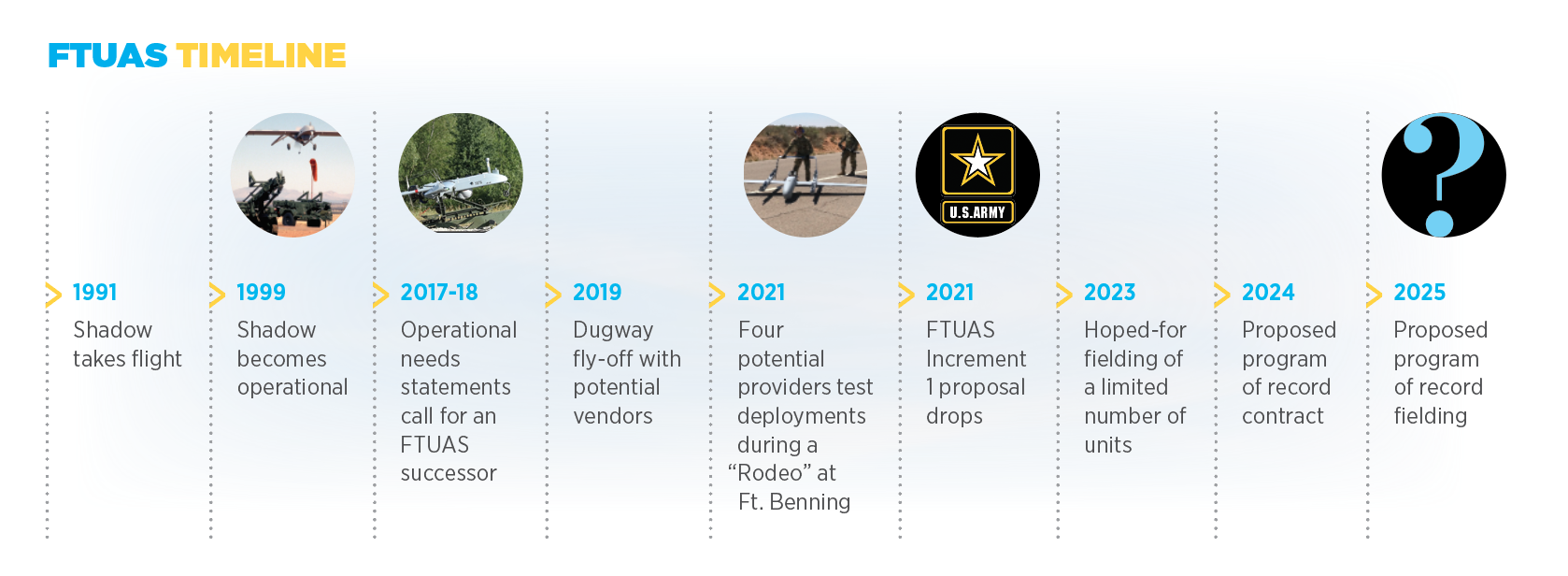

Greenawalt sourced today’s FTUAS operational requirement back to three different 2017-18 operational needs statements calling for a forward-deployed system that could be rapidly set up to operate runway-independently, and be easy to fly quietly over difficult terrain or heavily defended positions. “They were basically saying, ‘Hey, you know, the Shadow has been a great asset for us for the past 20 years,” he explained. “But as we look forward to MDO [multidomain operations], we need to be more agile, lighter; we need to rapidly deploy, with VTOL capability. We need something to replace Shadow. It’s done its job. It’s been a workhorse for us. We need something more maneuverable, something we can communicate with on the move, something we can get into theater very quickly, with minimal strategic airlift. That’s how the actual requirement came about.”

He continued: “The Shadow is tethered to airfields. It comes with a ton of equipment. The GCS [ground control stations] are humongous, labor-intensive and logistics-intensive.”

The next-generation FTUAS will draw on something that is truly rapid: advances in software precision, efficiency and portability. “It can be vertical takeoff and landing—that’s the transformational capability,” Greenawalt added. “They’re super-small, they’re light, they can pretty much be launched from anywhere—you’re talking a couple of laptops and a couple of monitors. They have command and control On-The-Move (OTM) capability. The soldiers are able to mount an antenna on the back of a Humvee and move across the CTC [combat training center] or battlefield with a tablet.

“We see these vehicles being organically maintained. They’re very simple. Shoot, it took the soldiers just a week or two to train up on these systems.

“Sound signature is another huge one,” Greenawalt said about the need for replacement. “You can’t hide the Shadow; it sounds like a freight train. These [new] things, they make a little bit of noise when you use the VTOL battery and are actually taking off. But when in forward flight, they’re almost undetectable.” (Textron Systems reports that the Shadow Block III reduces the acoustic signature by 60%.)

As always, there will be trade-offs. “Shadow has more payload capacity. And they have more range, because they travel a little faster. However, the FTUAS has more endurance. And when you’re not tethered to an airfield, you can move these things forward. The payloads are smaller and lighter as well.”

Textron Systems’ Aerosonde HQ, good to go.

INSIDE THE REQUEST

The FTUAS can provide what Army documents describe as “a distinct tactical advantage due to increased maneuverability through vertical takeoff and landing, improved command and control (C2) with an On-The-Move (OTM capability), a reduced transportability and logistics footprint, as well as significantly improved survivability due to reduced sound signature.”

Modular payloads are to include electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) sensors, laser designator and range finder, modern data links and encryption. Advanced Teaming capabilities also are called for (see the earlier “FTUAS Requirements: Among the Attributes” box).

Along with the specifications, a Capability Requirements Document required sections on how each submission addresses threats and define capabilities, key performance parameters and competencies, and details on attributes, spectrum requirements, intelligence supportability, weapon safety assurance, technology readiness and affordability. It also asks for DOTMLPF-P considerations—this allows leaders to analyze organizational capabilities through doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities and policy for future strategic decisions.

Again, the government is explicitly open to companies applying, which may well happen, since 23 firms responded to a previous Request for Information.

NEXT-GEN PRIMACY

In 2019, the Army conducted a fly-off with nine different commercial off-the-shelf FTUAS vendors at Dugway Proving Grounds in Utah. Two companies—Martin UAV and its V-BAT and Textron’s AAI Aerosonde—were asked to develop a VTOL successor that would deliver superior yet flexible ISR and situational awareness, with quicker setup by fewer soldiers. But a challenge expanded the downselection to include the L3Harris FVR-90 and the AeroVironment (then Arcturus) JUMP 20.

“We put those systems within five brigade combat teams and we demonstrated them for 12 months,” Greenawalt added, “gathering after-action reviews, lessons learned.” Then, this March, during a weeklong ‘Rodeo’ at Fort Benning, Georgia, “all the soldiers came back out and demonstrated the systems one last time for Army senior leaders and any other interested parties within the UAS enterprise. We wanted to see, ‘Where’s the technology at?’”

Simplicity came to the fore. “When we brought the soldiers back to the Rodeo, some of them hadn’t been with their system in over six months. It literally took them one day—super-easy to train”.

Feedback from platoon to command levels was processed. “It’s not to say the systems were perfect. Some did better than others,” Greenawalt said, without identifying them. “There were strengths and weaknesses with each system.” Still, “the flexibility provided brigade commanders in meeting their mission was just unmatched. Every single unit said, ‘hands-down, we’d take this system over what we have today’” (see our coverage at https://insideunmannedsystems.com/ftuas-replacing-the-rq-7b-shadow/).

Ironically, the findings were an embarrassment of riches; they didn’t narrow the field. But they allowed the Army to refine its draft requirements and abbreviated capability development documents. In August, AROC, the Army Requirements Oversight Council, approved the document setting out the going-forward FTUAS requirements.

FLYING TOWARD THE FUTURE

“We’re going about this in two separate increments,” Greenawalt reiterated. “Increment 1 can get capabilities to the warfighter now, But, he noted, some applicants might sit out the first increment and then compete “for being the program of record.” Also, the eventual choice may involve multiple variants. “With the speed that this technology is maturing at, I think it’s a real iterative approach. Whoever gets that contract in ’24 and we start fielding in ’25, this definitely isn’t going to be a program like Shadow, for 20-something years.

“Do we start looking at, ‘Hey, maybe some of our lighter units need this type of capability and maybe some of our heavy units have this mission and maybe this bigger air vehicle actually works better for them?’ There’s a lot to be determined, but I know we’re very flexible in our minds.”

Greenawalt’s clock was definitely ticking loudly. “We’re super-excited. Usually, to get these things in the field, it takes years. The Other Transaction Authorities give a lot more flexibility in how they field. To be able to do a Rodeo here in ’21 and say we’ll have it on contract and have some systems in the field in ’23 is good, if you ask me.”

AEROVIRONMENT’S JUMP® 20: THE CASE FOR FTUAS

When major UAS developer AeroVironment™ completed its acquisition of Arcturus UAV this past February, AeroVironment CEO Wahid Nawabi said the move, would “expand our reach into the more valuable Group 2 and 3 UAS segments.” AeroVironment sees the JUMP 20 as the vehicle to do that.

Arcturus alum Phil Mahill directs business development for AeroVironment’s MUAS product line. “We’re still vertically integrated: carbon comes in one side of the building and airplanes go out the other,” he said about the contribution emanating from what was Arcturus’ Petaluma, California, facility. Just as important, he noted, is how AeroVironment’s technology brings added advantage. The result: “We’re bringing a larger intelligence picture to all of our customers.”

JUMP-STARTING THE REQUIREMENTS

The new Army requirements, Mahill agreed, are a response to rapid technological acceleration. “Buying something off the shelf is one thing; having it be relevant in five years is another,” he said. “There’s constant pressure for improving performance. My opinion is, only a handful of credible companies can do it,” meaning truly meeting multiple FTUAS criteria.

Simi Valley, California-centered AeroVironment, he feels, can stick the FTUAS landing with more mission value per flight. “There’s just a huge amount of mission flexibility. Some of our customers are really compressing mission timelines and getting maximum use out of the aircraft. It’s more capability per flight hour than any other Group 3 platform,” he claimed.

The large vehicle (215 pounds maximum takeoff weight) can exceed the Army’s upgraded requirements requiring 25 pounds of payload (formerly five), offering up to 30 pounds usable payload now with an objective of 45 pounds. It can surpass original requirements such as eight hours of endurance, claiming 14-plus hours, along with an operational range of 115 miles.

Mahill lasered in on how JUMP 20 addresses the Army’s MOSA open systems payload requirement. “Our avionics architecture houses the autopilot but can also house a separate mission computer for hosting a variety of apps such as automatic target recognition. The avionics box allows us to literally plug and play—data links, payloads, cameras. We team with our customers to get best-in-class and latest technology into the aircraft.”

Yet, Mahill added, it’s easy to operate. “We would love to do another Rodeo. The soldiers said, ‘This is the easiest aircraft I’ve ever maintained.’”

FROM ROOTS TO FUTURE

“Our original [Arcturus] flagship was the T-20,” Mahill explained, recalling that catapult-launched, belly-landing craft. “The T-20 was exceptional in its ability to just stay aloft; we still have 24 hours of endurance. But we recognized that most of our customers just didn’t need that level, and would prefer VTOL capability as a trade-off. We saw the emerging VTOL market as a potential to provide a unique capability. We would eliminate the launch or recovery equipment, but still have the same high payload capacity and high endurance.”

Mahill summarized his argument for the JUMP 20. “I think we’re more dangerous than ever for our competitors. The partnership with AV integrates a new capability—everything the other guys are working on in their technology development road maps we can leverage into the JUMP. This system is multisensor. We’re kind of heading in the direction of a mini-Predator, and it costs a lot less. I just don’t know if anyone else is doing what we’re doing.”

L3HARRIS’ FVR-90: THE CASE FOR FTUAS

To be fair, we are the young kid on the block. But I am very pleased with the capabilities that we bring to bear, compared to some of the other guys.”

Peter Blocker, director, Tactical UAS, at defense giant L3Harris™ Technologies, doesn’t cede basic capabilities to the other candidates. But he concentrated the case for the FVR-90 around flexibility, payloads/endurance and digital engineering. In part, these came from two acquisitions and mergers.

In 2018, Latitude Engineering was acquired by what was then L3. This accessed both a vehicle and key quadrotor flight transition software (older versions of it are still used by some competitors). The second booster was the depth and resources offered by the 2019 merger between L3 and Harris Corporation.

“This is a purpose-built VTOL aircraft,” Blocker said, citing the model-based systems engineering approach developed within L3Harris. “We’ve embraced this to bring in technologies quicker, faster,” he said. “The whole system is digitized, the software, the hardware, where you can plug in a 3D model, plug in the new software and then quickly fly it in a simulation to see how well it works out.

“The Army talks about MOSA [modular open systems approach], or they talk about digital engineering these requirements. L3Harris has a pretty advanced model of how to do it. And we are making sure that that’s part of our deliverable to the government.”

PAYLOAD AND FLEXIBILITY

“One of the key things about our systems is the ability to carry a tremendous amount of payload versus gross takeoff weight,” Blocker said. “Our gross takeoff weight is on the order of 120 pounds and we can carry a useful load of 50 pounds across your fuel and the actual weight of your payloads. Typically, we run about 10 hours of endurance on 20 to 22 pounds of fuel; thus, it brings you about just under 30 pounds for the actual payload. We can hang 10 pounds or under on each boom, coupled with an EO/IR ball in the nose. We can carry up to about 22 pounds in the nose alone.

“It can be very expeditionary,” he continued. “It can be a logistics bird, it can do ISR, we’ve already found some EW payloads on it. Coupled with the digital model, things can be integrated very quick.”

The FVR-90 run-up has supported continuous improvement, Blocker said. “We made a dozen, 15 changes to the system over the last year, and each customer knew about every single one of them the entire time. For instance, we did not have the capability of recharging our VTOL batteries in flight. We do now.”

Such upgrading will continue. “One of the comments at Rodeo was that if an enemy was watching they would know exactly where the units work. So we have ideas of how to change software to where we take off in a completely different way to not show exactly where the command center is.”

Blocker returned to L3Harris’ developmental paradigm for FTUAS. “We’re good with making sure that the end customer gets what they want—in this case, a true digital-engineering or model-based systems engineering approach to allow the end customer to integrate third-party software and applications hardware very rapidly. That’s one of our key strengths that we’re going for.”

MARTIN UAV’S V-BAT 128: THE CASE FOR FTUAS

Group 2 transportability, group 3 capablility.” That’s the case Heath Niemi, vice president of business development for Shield AI, makes for Martin UAV’s V-BAT 128 being the FTUAS choice. “It’s Group 2 transportability by weight; it’s Group 3 capable.”

At the Army’s FTUAS Rodeo in March, the Martin V-BAT was unique as a tail-sitter. Then in July, the Plano, Texas, company became the most recent of our FTUAS four’s business acquisitions with its purchase by San Diego-based artificial intelligence firm Shield AI. The result will allow the integration of Shield’s Hivemind® AI autonomy stack with the V-BAT, enabling GPS- and communications-denied operations and swarming.

Niemi, who spent 25 years in Army aviation, noted that the Martin’s earlier V-BAT 118 had proved itself as the first VTOL to fly on a Coast Guard vessel and with the Marine Corps, Martin UAV’s oldest customer. He added that the V-BAT was evolving even during the Rodeo: While the 118 model was being officially evaluated, Niemi was demonstrating the 128 in another exercise. “I was a quarter-mile down the road, flying for infantry platoons.”

To explain the 128’s improved capabilities, Niemi cited a “10% rule” within UAS circles. “They believe that the max gross weight, not including eight hours of usable fuel, there’s about a 10% ratio for usable payload.” The V-BAT 128’s engine adds 11 horsepower, with upgraded ducts and other improvements. “That has produced an amazing amount of extra power,” Niemi said. “On a 125-pound drone [the 128’s weight], you would think we’d only have 12.5 pounds of usable payload; we’ve increased the payload capacity from eight pounds to 25, so, we’re over 20%.”

He continued: “We’ve increased the endurance to 11 hours. We have 130 kilometers [81 miles] range.” Interchangeable payloads can be deployed, and in September, Martin UAV and Northrop Grumman conducted flight testing of a V-BAT with GPS-denied navigation and other capabilities. “I think the V-BAT is uniquely suited for Group 3-sized payloads, and Northrop Grumman Corporation and Martin UAV bring more than 30 years of UAS experience to this partnership to produce and deliver the V-BAT 128 for the FTUAS program.”

V-BAT AT BAT

Niemi turned to “transportability and tactical flexibility” as V-BAT 128 advantages. “It can be moved in a Black Hawk helicopter, a Humvee or in the back of an F-150 pickup,” he said. Setup time by two soldiers is put at 30 minutes; the footprint at 12 feet by 12 feet. Hovering capability will be increased. Then, Niemi said, “I can hide behind a set of trees and my ISR payload can look around. You can imagine taking off in the back of a building or”—recalling recent headlines—”an embassy.”

Even as the Army deliberates over Increment 1, Niemi described how the V-BAT has expanded to support other branches. “Our drone is uniquely suited for maritime operations,” he said, noting the 128 winning a prototyping contract in this April’s U.S. Navy Mi2 Technology Demonstration. “We know how to do spares kits for 45 days at sea with no logistic resupply, we know how to fly in saltwater, we know how to fly in winds that are turbulent on the deck, gusty, unpredictable.

“It really is a joint service solution,” Niemi said about the V-BAT, part of a plan to make its technology more capable and scalable, including for commercial applications. “When you look at the systems ramp-up,” Niemi declared, “we have an amazing road map.”

TEXTRON SYSTEMS’ AEROSONDE® HQ: THE CASE FOR FTUAS

he Aerosonde HQ—as in hybrid quadrotor—has been scaled up and purpose-built to meet the Army’s stated requirements. In doing so, it draws on nearly 550,000 operational hours that Textron has flown on the Aerosonde platform, as well at 1.3 million hours on the Shadow platform with the Army.

“Incumbency is important,” said Wayne Prender, senior vice president, air systems for Textron Systems, which manufactures in 16 countries. “What it provides us is an intimate understanding of how these systems are utilized out in the field, listening to what their requirements are.” Now Aerosonde HQ seeks to leverage that incumbency to replace the Shadow at the brigade level. “The Army has clearly identified the need for a system that is more agile and responsive than the Shadow system,” Prender added. “We firmly believe that what the Army’s asking for here is a combat-proven system that has no room for failure.”

EARLY DAYS

In its earlier incarnations, Aerosonde made its mark as a meteorological weather and research vehicle. “Flying into hurricanes required very robust aircraft, a high reliability that provided information that had never been gained before,” Prender said. “We took our Shadow experience and began to militarize or ruggedize the system for military.” By 2016, an Aerosonde VTOL Hybrid Quadrotor (HQ) was offering ISR capabilities.

Today, a small footprint and rapid setup rank among the requirements Prender believed Aerosonde HQ could more than meet. “The BCT at Fort Polk, [Louisiana], they literally took our system put it in a Black Hawk, flew into a landing zone, and were up and operational in less than 30 minutes.”

The Aerosonde has evolved from a catapult craft to what the company calls “no stands or hands.”

“There is no need for not only the existing launch and recovery system our Shadow system requires, but it has no need for stands or jacks or even soldier-assisted launch and recovery,” Prender explained. “Our system is set up, the guys are able to back away from it and the system autonomously takes off, transitions, moves out, executes the mission set. It autonomously identifies a recovery location and transitions into a vertical descent and easily touches down on the ground.”

Prender also praised sister company Lycoming Engines for its reliable power plant. “We have amassed over 550,000 flight hours with our Aerosonde product using only a heavy fuel engine,” he said. Since the Aerosonde HQ runs on common JP-8 fuel, “that minimizes any logistical concerns about moving fuel or additives across the battlefield. That’s definitely something that we’re a firm believer in, and we’re going to hold to as we continue to evolve our system.”

Another aspect of ruggedness is being able to operate in the kind of foul weather than could ground the Shadow. Rain resistance has been upgraded to two inches per hour. Other improvements include greater standing range with improved payloads, a TASE400 LD long-range targeting payload and a mission computer that can match an evolving use case.

“We are very happy to see this capability be provided into the hands of soldiers, and made operational very quickly,” Prender concluded. “We believe Aerosonde HQ is perfectly situated to provide the brigade combat teams with the agility and maneuverability they need to support their fight. As the incumbent for 20 years, side by side with the Army, we can do no less than to give our best effort.”