Russia’s Black Sea Fleet has been reduced to a defensive crouch by cruise missiles and kamikaze drones.

The many large and small cruise missile-armed surface combatants, attack submarines and landing ships of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet (BSF) should, on paper, easily dominate the waters around Ukraine.

But confronted with a mix of Ukrainian land-based and air-launched cruise missiles, and increasingly frequent raids by naval kamikaze drones, the BSF has been reduced to a defensive crouch—a stunning strategic victory for a country compelled to scuttle its only sea-going frigate when Russia invaded in February 2022.

Technically, remote-control vessels have existed for roughly a century, and Ukraine’s drone boat tactics echo the fireships launched at the Spanish Armada, British and Italian World War II naval sabotage ops, Japanese Shinyo kamikaze motorboat units, and Iranian interdiction of the Persian Gulf. But make no mistake: the Black Sea Drone War is historically unprecedented—a campaign in which one side’s primary sea-based combat forces are expendable unmanned vessels.

Admittedly, after the first spectacular USV attack on Sevastopol on Oct. 29, 2022, which damaged the frigate Admiral Markaov and minesweeper Ivan Golubets, the BSF assumed a defensive stance in Sevastopol, building ever more elaborate harbor defenses to complicate ingress. This minimized damage from multiple subsequent USV attacks.

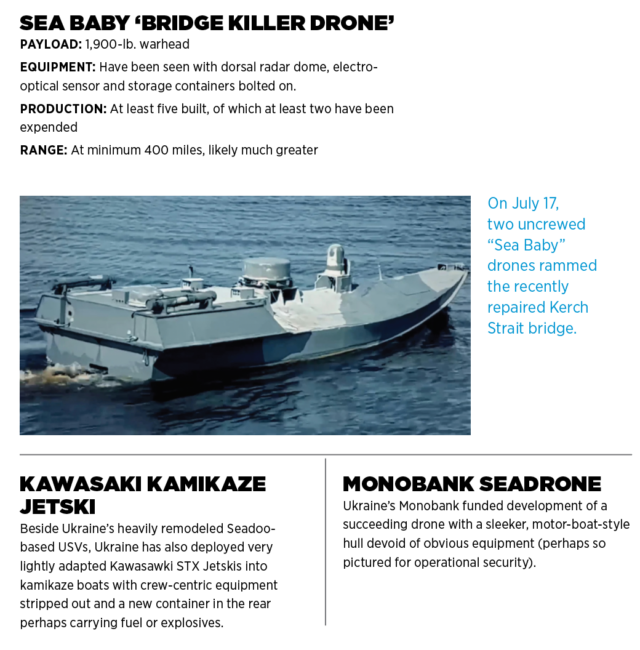

But in May and June, attacks on Russian intelligence ships Ivan Khurs and Priazovye indicated Ukraine was now deploying an improved generation of Magura V5 kamikaze USVs capable of intercepting ships at sea.

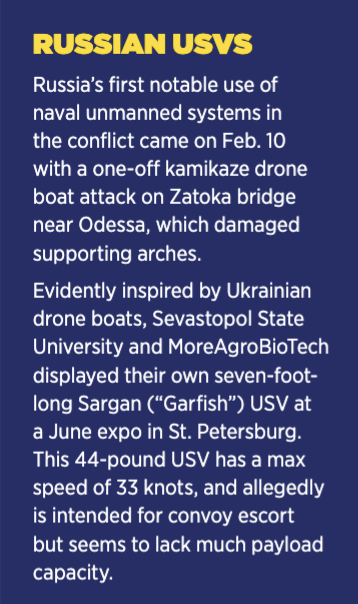

The implications of this extended reach truly sank in on July 17 when two uncrewed “Sea Baby” drones rammed the recently repaired Kerch Strait bridge and detonated a half ton of explosives, partially collapsing the road bridge to Crimea, rupturing a span and killing two civilians. Damage to the critical bridge won’t be repaired until November.

Then, on Aug. 5, SBU drone boats assailed the BSF’s secondary base of Novorossisyk on Russian soil, heavily damaging tank landing ship Olenegorsky Gornyak and blasting a two-meter hole in the oil tanker Sig. Later that month, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky awarded battle honors to heretofore unknown 385th Separate Special Purpose USV Brigade presumably conducting these ops. Finally, Sept. 13-16, Ukrainian drone boats went on spree hunting Russian missile corvettes: three attacked Vasily Bykov at sea; others severely damaged Samum near Sevastopol; and at least one was destroyed assailing the Askold.

In an interview, Ukrainian military intelligence chief Krylo Budanov notes the indigenous USVs were in serial production, but conceded “[Russian defenses] destroy 60%, maybe even 70% [of USVs]…However, the remaining 30% is still a problem for them.”

Admittedly, sub-optimal warheads have prevented impacting USVs from outright sinking Russian warships, while Ukrainian cruise missiles have done so. However, the USVs have succeeded in keeping the BSF ships largely cooped up in port, in stark contrast to the war’s early weeks when they pressed Ukraine’s coast line with shelling and threatened amphibious landings.

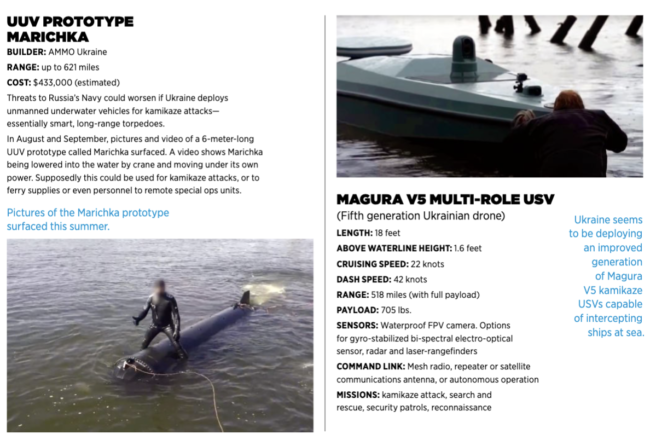

UKRAINIAN UUVS: FUTURE TERRORS OF THE BLACK SEA DEEP?

Russian vessels and port facilities have effectively employed heavy machine guns, autocannons, electronic warfare systems, helicopters and even Be-12 amphibious planes to detect and destroy approaching Ukrainian drone boats. But threats to Russia’s Navy could worsen if Ukraine deploys unmanned underwater vehicles, or UUVs, for kamikaze attacks—essentially smart, long-range torpedoes.

In August and September, pictures and video of a 6-meter-long UUV prototype called Marichka surfaced. It’s built by the Ukrainian non-profit AMMO Ukraine, which is soliciting funding to complete development. AMMO claims the UUV will attain a range of 621 miles and cost roughly $433,000 apiece. A video shows Marichka being lowered into the water by crane and moving under its own power. Supposedly this could be used for kamikaze attacks, or to ferry supplies or even personnel to remote special ops units.

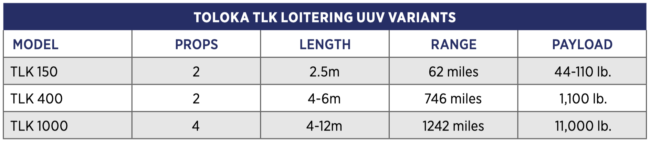

A smaller UUV, the 2.5-meter-long Toloka TLK-150 “loitering torpedo,” was also seen under development in April by the Brave1 nonprofit. It has two electrically powered propulsors mid-body, a tall dorsal mast mounting surface-peaking sensors and communications, and a max payload of up to 110 pounds. Brave1 hopes to develop a family of Tolokas of varying capacity.

It’s unclear how close either project is to resulting in an operational platform. However, if they result in an effective weapon, they will further imperil operations by Russia’s Black Sea Fleet and create a need for distributed anti-submarine or torpedo defense to guard against attack.

UKRAINE’S DRONE BOATS

The first wave of combat USVs deployed by Ukraine were built on the hulls of civilian jet skis. But in the spring of 2023, several new types of Ukrainian USVs were spotted, showing continual evolution. Ukrainian officials state USVs are in serial production at an underground facility.