As drone threats proliferate, private and government efforts (start to) respond.

The FAA estimates that by 2024 about 2.3 million drones—1.5 million recreational drones and model aircraft and more than 800,000 commercial drones—will be registered to fly in U.S. National Airspace System (NAS). As drone numbers increase, so do reports of negative encounters with them. In the past two years, the Department of Homeland Security has logged more than 2,000 drone sightings in and around U.S. airports and more than 8,000 illegal cross-border drone flights at the southern border.

“The drone threat continues to evolve at a rapid pace as drones and the sensors and technologies associated with them become more affordable,” noted Casey Flanagan, a former FBI technician specializing in counter-drone. Flanagan, who also is the current president of Richmond, Virginia-based AeroVigilance, a counter-drone consulting, training and services provider, offered a prediction: “The nefarious use of drones will ultimately only be limited by the imagination and technical abilities of those who use them.”

This threat continues even as the law that gave a limited group of federal officials the authority to detect and mitigate will soon expire. Consequently, it’s worth surveying the state of peril, the tech to defeat it and the actions necessary to create safe skies.

THE HOVERING THREAT

During a hearing focused on the evolving threat that drones pose to the U.S. in the Senate’s Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, Brad Wiegmann, the Justice Department’s deputy assistant attorney general, national security division, warned that it’s “only a matter of time” before a drone attacks a mass gathering in the country.

Why? Because the same characteristics of small commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) drones that benefit society also make them dangerous in the wrong hands. Low cost, widespread availability, mobility, speed, range, maneuverability and compactness allow them to fly over barriers, scout out critical information and remotely deliver lethal and non-lethal payloads with great precision.

For these reasons, COTS drone used as lookouts and attack vectors overseas has escalated. Across Afghanistan, Yemen, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, drones have been used to explode over people and target commercial aircraft at civilian airports. And Ukrainian forces have used COTS drones for everything from forward observation and adjusting fire to delivering grenades.

The nefarious use of drones is not limited to locations far away. Since 2019, in the U.S. drones have collided with an Army helicopter, and enabled attempts to drop explosives near a Georgia mobile home park and deliver contraband into the Fort Dix Prison.

And then there are the clueless and careless flyers. The FAA has received more than 100 reports a month of problematic UAS activity monthly over the past two years. The agency has characterized this as “a dramatic increase.”

Acting DHS Assistant Secretary for Counterterrorism Samantha Vinograd testified this summer that during the agency’s 70 counter-drone protection operations at large events, FBI teams detected 970 noncompliant drones in restricted airspace. Additionally, the TSA reported 65 cases where commercial airline pilots had to take lifesaving evasive actions to avoid colliding with drones.

D-Fend Solutions, an Israel and McLean, Virginia-based counter-drone company, tracks these types of global drone incidents. Jeffrey Starr, the company’s chief marketing officer said, “We‘ve seen a sharp increase in drone incidents across an incredibly diverse set of occurrences, geographies, sectors and incident types. These include attacks, collisions, espionage, harassment, privacy violations and smuggling.

“The first wave of early incidents mostly involved the military, national and homeland security, law enforcement, airports, and border sectors,” Starr continued. “But we now also see a new wave of incidents and heightened concern from ports and harbors, VIP and executive protection, maritime operations and critical infrastructure including stadiums and arenas, prisons, and government buildings and landmarks. The drone risk is spreading.”

All these incidents underscore the urgent need for effective counter-UAS, or C-UAS, technologies and the related authority to detect and mitigate drones in the homeland.

KEEPING PACE WITH THE TECH

The evolution of drone technology to include the methods in which drones can navigate through the airspace presents challenges for counter-drone operations.

AeroVigilance’s Flanagan explained: “The variety of drones and their technical capabilities will require a defense-in-depth posture that includes various methods to detect and mitigate any drones that may be considered to be a credible threat to the safety of the public or our critical infrastructure.”

Those enhanced drone tech capabilities include features such as GPS-enabled autonomous waypoint missions and optical flow, as well as frequency hopping. These advancements allow solutions to detect the physical signatures of the drone and not rely solely on radio frequency (RF) detection.

The operational environment itself also presents challenges for counter-drone tech employment. Many events that require protection have an associated high RF interference environment, including antennas, communications systems and media transmissions. This can limit options. Jammer-based solutions, for example, could potentially disrupt critical comms systems operating in the area.

Add to these hurdles the nuances of specific mission sets. For VIP protection, counter-drone systems must be transportable enough to provide a moving bubble of protection, be quickly set up and configured, and dismantled and reassembled.

And so counter-drone companies have stepped up their enhancements. Various sensors detect, locate/track and classify/identify drones, ranging from radio detection and ranging (RADAR), passive RF, electro-optical and infrared (EO/IR), and acoustic. They employ electronic and kinetic, or physical, mitigation actions such as jamming, spoofing, net guns/specialized projectile devices, kinetic mitigation, laser weapons and high-power microwaves. Some even use drones to counter other drones.

D-Fend Solutions‘ flagship product, EnforceAir, for example, is an end-to-end counter-drone solution that automatically executes cyberdrone detection and takeover mitigation of rogue drones for safe landings and outcomes.

In 2021, the Ministry of the Interior of Slovakia used the EnforceAir Ground-Level Tactical Kit during an open-air Holy Mass in Šaštín, Slovakia, to provide 360-degree coverage. EnforceAir ultimately fended off a rogue drone, sending it back to its original takeoff position, far away from Pope Francis, 90 bishops, 500 priests and an estimated 60,000 worshippers.

“Thankfully, with the help of our counter-drone technology, this incident ended safely,” said a D-Fend Solutions source. But, he continued, “this incident does, however, reflect the growing danger posed by drones to national security around the world, to critical infrastructure, civilians, world leaders and large events.” (for additional coverage, see https://insideunmannedsystems.com/d-fend-reprograms-rogue-drones/)

James Poss, Maj. Gen. U.S. Air Force (Ret.) and IUS columnist, agreed that the drone threat continues to grow. He pointed to the effective use of commercial drones in Ukraine as an indicator of things to come: “If small commercial drones can have such an impact on the battlefield, imagine the impact terrorists could have using them in our homeland.”

Poss continued: “In the U.S., we spend a lot of time preparing for the next air attack to come across the hemisphere. The next attack may come across the parking lot.” This “frightening prospect” reinforces the need for counter-drone technology and enhanced counter-drone authorities in the U.S.

Northrop Grumman’s Kent Savre, Maj. Gen. U.S. Army (Ret.), director for the company’s precision weapons operating unit, echoed Poss’ observations. “The same types of commercial drones we see helping Ukraine can provide an asymmetric advantage to those who would do us harm right here in the homeland,” he said.

To meet the threat, Savre’s team designed a scalable and modular artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML)-enabled Mobile Acquisition Cueing and Effector, or M-ACE, system to detect, identify, track and mitigate potentially dangerous drones. However, the company, and others like it, has been stymied from fielding any systems domestically, despite interest from law enforcement agencies, due to legal limitations on counter-drone technologies.

LAW DEFLECTS DETECTION

Currently in the U.S., only a handful of federal agencies have the authority to even detect rogue drones, let alone mitigate them.

A cluster of federal criminal laws within Title 18, written mostly to protect aircraft and wireless transmissions, preclude state and federal law enforcement agencies from taking counter-drone actions without specific legislative authority. (See the August 2020 interagency “Advisory on the Application of Federal Laws to the Acquisition and Use of Technology to Detect and Mitigate Unmanned Aircraft Systems” at https://www.cisa.gov/publication/advisory-application-federal-laws-acquisition-and-use-technology-detect-and-mitigate).

It was not until 2017 that the Department of Defense became the first federal agency to receive Congressional authority to detect and mitigate drones (10 U.S.C. §130i). That same year, Congress extended similar authority to the Department of Energy by amending the Atomic Energy Defense Act (50 U.S.C. §4510).

A year later, Congress included the “Preventing Emerging Threats Act of 2018” in the “FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018” (FAARA 2018). This Act expanded federal counter-drone authority to the DOJ, FBI, DHS and Coast Guard, allowing them to mitigate credible drone threats to certain facilities, such as federal prisons, courthouses and other protected assets. It was set to expire in October.

Federal leaders have implored Congress to both renew and expand its C-UAS authority. As DHS’ Vinograd testified, “there are significant gaps in our ability to protect the homeland from drones.” She explained that during these past 4 years, “the demand for counter-drone support has far outstripped the federal government’s limited resources.” Her agents, she said, could only cover 0.05% of the more than 121,000 events requiring counter-drone protection.

The feds have asked Congress to expand counter-drone authorities to the TSA, local law enforcement and certain critical infrastructure stakeholders.

“DHS relies on partners all around the country to help protect the homeland. We can’t be everywhere,” Vinograd said. “What we know is that the threat posed by UAS is widespread across the country, and it is critical that our partners have the authority to help protect the homeland.”

FEDERAL RESPONSES

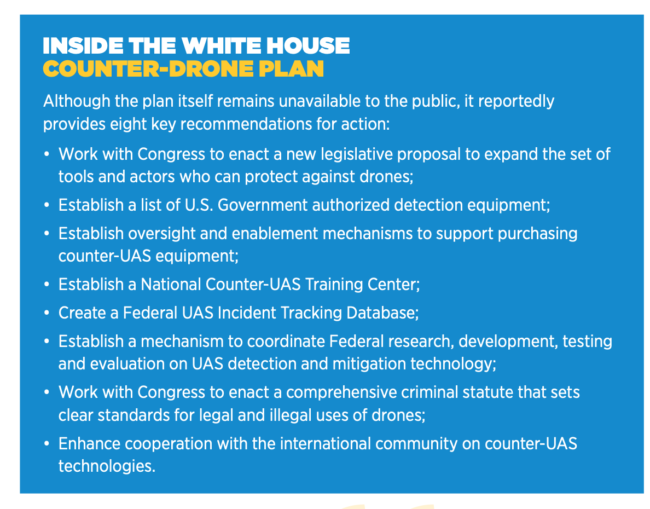

The White House has taken a keen interest in counter-drone. In April, it released the nation’s first Domestic Counter Unmanned Aircraft Systems National Action Plan. It remains unpublished (see “Inside The White House Counter-Drone Plan”). Then in August, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, in coordination with the National Security Council, hosted the first White House Summit on Advanced Air Mobility. While the event read-out focused on electric vertical takeoff and landing developments, the actual agenda devoted half a day to counter-drone topics.

In the interim between the White House’s plan and summit, Congress got going.

In July, Michigan Sen. Gary Peters, in cooperation with Sens. Johnson, Sinema and Hassan, introduced the bi-partisan “Safeguarding the Homeland from the Threats Posed by Unmanned Aircraft Systems Act” of 2022. The bipartisan group intends to continue to enhance the counter-drone authority originally granted to DHS and DOJ while additionally authorizing:

• State, local, tribal and territorial (SLTT) law enforcement and owners and operators of critical infrastructure (including airports) to use certain detection-only capabilities.

• A limited pilot program for up to 12 state and local law enforcement entities each year to engage in both detection and mitigation activities. This would include training, vetting and the requirement to follow the same operational and privacy rules as federal agencies.

• The marshal service to protect high-risk prisoner transports.

The bill was sent to the Senate as a whole for consideration on Aug. 3. Only one in four bills get reported in this manner out of committee. While that’s a good sign, its fate still remains to be seen.

WHAT NOW?

As the White House plans and chats and Congress ruminates on what authorities to continue or expand for counter-drone, some say the FAA will soon be creating a Counter UAS Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC). These time-limited, purpose-driven ad hoc groups provide information, advice and recommendations to the FAA. The FAA concluded its Beyond Visual Line of Sight ARC work earlier this year and issued a 400-page report. That said, so far the FAA ARC website does not reveal any further details on such a C-UAS ARC.

Leaning forward, the non-profit DRONERESPONDERS has announced its plans to launch its own “Counter UAS Working Group.” Its stated goal is to share information on new developments and support what it perceives as the continued momentum of C-UAS efforts.

Is there really momentum or are we at a critical drop-off point for counter-drone authorities? The counter-drone bill is a great step in the right direction. We need it now, though, before there’s a gaping legal hole for critical protection against rogue drones.