AeroVironment’s President/CEO defines the culture, teamwork and execution behind the Mars Ingenuity breakthrough.

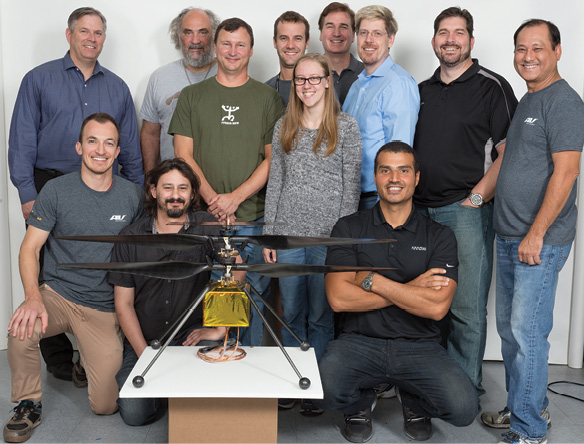

Wahid Nawabi, the head of multi-domain unmanned systems developer AeroVironment, was buoyant. Engineers and staff from NASA and its Jet Propulsion Laboratory had just visited to debrief in the wake of the Mars Ingenuity Helicopter’s shift from proof of concept to an operational technology craft flying above the surface of its namesake thin-atmosphere world. As a key partner, AeroVironment had developed components from the propulsion system to wiring and landing gear.

“Their words, not mine, that this was the best, the best, collaborative partnership that they could ever even wish for,” Nawabi recounted. “I asked them, ‘Is there anything that we could have done better?’ ‘No, Wahid, there’s nothing. We didn’t even feel like a different team.’ The collaboration was that close, that tight, that important.

“The credit goes to our team,” Nawabi said. “I am just a messenger for them.”

Like a proud technological father, Nawabi defined the principles behind his company’s ability to deliver unique, even trail-blazing, solutions. His tentpoles? Collaboration, a culture of innovation and mission-driven execution.

THE ROOT OF SUCCESS

“Everything that we do starts and ends with collaboration,” Nawabi explained emphatically. “When you’re designing a system of systems solution, it is by far one of the most, if not the most, important, attributes of the team and the entire mission.

“You can’t do a project like this without having an incredibly strong collaborative team” Nawabi continued. “Taking things that have never been done before is just what we thrive on. The people we hire, train and develop have an appetite for daring endeavors. That’s No. 1. No. 2, you’ve got to be willing to work passionately as a team. This is not a job. This is what they want to do.”

Nawabi’s description of the helicopter project sounded like a space-age Russian nesting doll. To get to Mars, it had to be specced to fit within the Perseverance rover, which had to fit within the payload bay of the rocket that would carry them from Earth. Tested as an aircraft on our planet, the helicopter functions as a spacecraft on Mars. And the fight control computer, the autopilot, had to be designed in close coordination with JPL.

The stakes around Ingenuity were higher than usual, Nawabi pointed out; after all, it’s harder to fix something that’s 170 million miles away. “You must be able to design systems that 100% cannot fail,” he said. “It’s not like you can launch this thing and go return it and fix it. Every single intricate detail has to be done just perfectly right.

“You’ve got to be able to work in an environment where there’s a tremendous amount of unknowns. This has not been done before, so you have to figure out a way to do it yourself.”

A multi-year project such as Ingenuity requires effective planning. Nawabi endorsed a PDCA model—plan, do, check, act—and ticked off key milestones.

“You develop a theory—what is this concept, and what are we going to achieve at the end of this? You check the concept to make sure it’s valid.”

Next, Nawabi outlined, ‘you develop a set of requirements as a result of that.” For Ingenuity, those requirements included the physics of flight on Mars; size, weight and dimensions compatible with fitting into the rover and the spacecraft; and sufficient autonomy to function far from Earth’s signaling.

“And then,” he continued, “those requirements make it into a project plan that says, ‘Here’s how I’m going to achieve that outcome.’ And then the work starts to be divvied out.

“You test it. And if it works, you develop it more, and you test it again, and you take the learning and you keep improving it.”

MARTIAN MILESTONES

“On Mars, it’s a lot more difficult,” Nawabi noted, citing another set of milestones. “I’ve got a system that works in the lab. Would this system become bulletproof under all these extreme conditions: radiation, shaking, vibration, rattle, extreme temperatures? It will not fail, because it cannot fail—the entire mission’s over.

“What if this thing lands, and it gets hit really hard; let’s test the landing system, make sure it’s robust. The mechanical systems that have to open for this thing to become operational. Powering it up, the solar panels working—do we get enough energy to land and complete the mission? All these things are very, very critical.”

Six flights in, Nawabi turned the proverbial telescope around to peer into the future.

“There already are several concept missions that a flying device on Mars can do much better than a ground robot can do—that by itself is a complete new dimension. For example, samples on Mars in different places have to be meticulously picked up. You can use a rover, but what if the rover failed after taking three samples? You can have an insurance policy with a UAV. You don’t risk a billion-dollar mission with one point of failure. And there are so many other examples. The rover does very, very good things. But it does go slow. And its reach is very limited.”

Nawabi continued: “For every single potential mission in the future, for not only Mars, for any other planetary operations that mankind will take on—we believe it dramatically changes our ability to really progress in exploration and eventually habitating Mars with humans.”

Before concluding, Nawabi mirrored his earlier comment that collaboration bookends all of AeroVironment’s projects.

“The most important thing from the beginning,” Nawabi noted, “is that you have a team that is fully committed and believes in the outcome of the mission. You’re going to run into an enormous amount of uncertainty, most likely some setbacks, challenges, questions, problems. You can’t force that belief, it has to come within themselves.

“You take a daring challenge, and a team of very talented people, both at AeroVironment and at JPL—the primary two parties, along with other players—essentially had a moment that has not been repeated since a Kitty Hawk moment 100-plus years ago. Achieving that as a team, across different locations during a pandemic—how could you not be inspired? Just like we look now at how aviation has transformed and changed our lives, and humanity’s lives all over the world, for the last 100 years. The same could be said about this 100-plus years from now.”

One other aspect of collaboration needed to be addressed: how does Nawabi see his role as a leader for such a complex project?

“I am just here as an enabler to remove the barriers, to create the environment and create the atmosphere, so these people can unleash and just basically live up to their potential. We have a thing within AeroVironment that once you know what you have to get done in terms of the mission objective or the customer requirements, get the hell out of the way and let those people run. We let them work as free, collaborative, incredibly talented, incredible minds.”