Which method will get commercial drones flying first? Waiting for the federal government to evolve workable drone rules or devolving federal authority to the states to see if the states can move faster?

The thought struck me as I was talking with Kansas and Oklahoma state legislators at the Oklahoma-Kansas UAS (unmanned aircraft system) Tech Forum in September. I had just given my speech and I had encouraged state, local and tribal authorities to take a greater role in drone rulemaking because I think they can move faster than the federal government. These gentlemen had clearly been thinking about how to make their states more drone-friendly, but the thought that they could move faster than the feds in rulemaking was something they hadn’t considered. One legislator explained: “We’ve always been told the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) has primacy over states for aviation and locals don’t have a role in drone regulation—it’s a federal responsibility and that’s it. End of discussion.”

Must it be FAA?

Well, should drone regulation be completely a federal responsibility? Should we treat low-altitude drone flight more like cars than airliners? More importantly, can state governments get to commercially viable drone regulations faster than the feds?

The FAA correctly asserts its primacy in aviation regulation over states—an authority that goes back to the 1926 Air Commerce Act that gave the federal government the overarching responsibility to issue air traffic rules, license pilots, certify aircraft, establish airways, and operate air navigation aids. At the time, aircraft advocates believed the feds needed primacy to ensure aircraft flying between states didn’t face a patchwork of local laws that would inhibit commerce. Commerce was the driving factor, which is why the Secretary of Commerce ended up with civil aviation. Safety didn’t become the prime regulatory concern until Congress moved aviation out from Commerce and created the independent Federal Aviation Administration in 1956.

Drones are the biggest change agent in aviation since the invention of the airliner. They challenge the basic tenet of aviation safety—that a pilot can always “see and avoid” collisions even if all other safety mechanisms fail. Creating a system that allows drones to fly alongside manned aircraft will bring new kinds of risks and will require more sophisticated air traffic automation than we’ve ever seen—a difficult, but certainly doable task in this exponential age of technology. Is an independent agency that prides itself on putting safety above all else ever going to be willing to compromise on its most basic tenet in the interest of commerce? Will the FAA move quickly with unmanned air traffic automation even though a successful automated system will completely upend the way it’s been managing air traffic for decades? Will the states be more agile in responding to commercial pressures more quickly without sacrificing the safety we all hold so dear?

24 Years of Caution

From an industry perspective, the FAA has been creating drone regulations slowly and cautiously. I put the beginning of the modern drone era in 1994 with the first flight of the MQ-1 Predator (the first drone capable of safe, sustained beyond-line-of-sight flight). It took the FAA 24 years from this point to publish their first drone rules. That’s the same amount of time it took for the Wright Brother’s first flight, inauguration of America’s first airline and the creation of an entire agency to oversee commercial aviation in the U.S. And the first FAA drone rules aren’t close to what the commercial operators need to meet market demands and build a viable commercial drone industry. Drones can’t fly over 400 feet, can’t be more than 55 pounds, can’t fly over people, can only fly in daytime and can’t fly beyond the visual range of their pilot. Rules for large drones are (hopefully) going better, but let’s face it—the U.S. Air Force has been flying large drones safely alongside manned aircraft for 26 years. Commercial-sector-enabling small UAS rules have encountered snag after snag. Rules for flights over people are snarled over a fight with the Departments of Defence and Homeland Security (DOD and DHS) about drone remote identification, with no word on regulations for more than a year. Official rulemaking for BVLOS (beyond visual line of sight) flights hasn’t been started yet and two years’ worth of Pathfinder experiments only yielded closely guarded procedures for extended visual line of sight (EVLOS) flight. Not only are there no rules even for EVLOS, but the Pathfinder company involved is selling access to the procedures they developed with the FAA during the program. A bit off topic, but shouldn’t that information be for everyone’s public benefit?

Let States Lead

Back on point, let’s think about this some more. The Integrated Pilot Program (IPP) is supposed to be researching how state, local, tribal and federal officials rules would work together to regulate small drones, but the program has already excluded local management of airspace, no matter how low. What if Congress voted to allow states to develop their own drone rules below 200 feet? That would leave 200-400 feet for eventual FAA rulemaking, but give the states a chance to more swiftly enact viable drone rules. States that don’t want to opt in could remain under federal control. I believe several states have the expertise and motivation to create commercially viable drone rules that they could harmonize with other states quicker than the FAA will develop viable drone rules for nationwide operations.

I can hear the commercial drone lobby crying “patchwork laws!” as I write this. They fear states will create drone rules that vary wildly, forcing commercial drones to comply with 50 sets of state rules instead of just one set of federal rules. This is a valid concern, but if it’s clear the FAA won’t or can’t move quickly on workable small drone rules, wouldn’t it be better to put some faith in the reasonableness of our state law makers versus waiting years, maybe decades, for the FAA to unlock the industry? Did multiple state automotive rules prohibit the trucking industry? If Amazon, Walmart and Google can track the individual preferences of millions of customers, can’t they track 50 sets of drone rules? Won’t a local approach to rules encourage local drone industries versus big conglomerates and monopolies? States reliably harmonize laws when there is economic incentive to do so via the Uniform Law Commission. Indeed, the ULC has already drafted a “Drone Trespass” law that sets rules for flying low over private property that can be used as a cornerstone for state commercial drone rules.

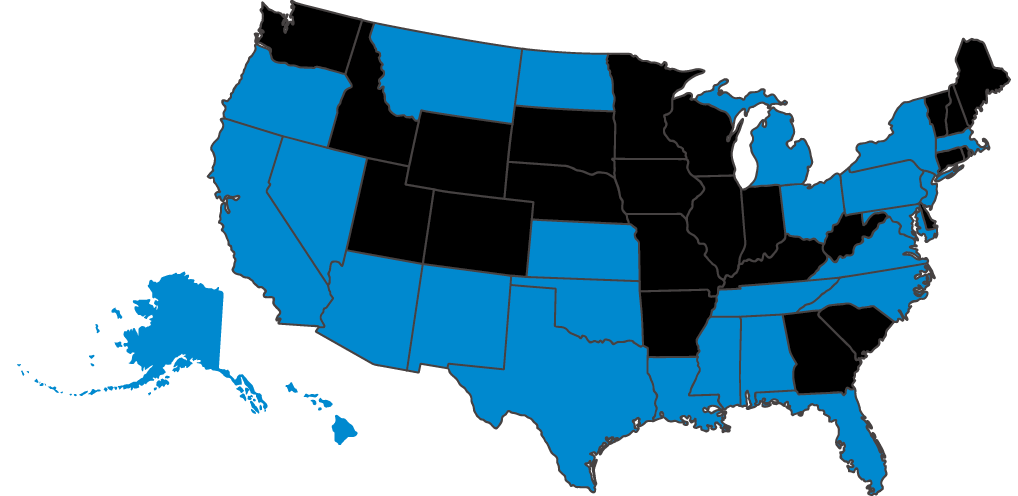

Several States in part have everything needed to gather data, test proposed rules in a safe environment, and quickly draft state drone laws for other states to adopt or use as guidance. Some states that can lead this effort today include:

NORTH DAKOTA: North Dakota has an FAA Test Site, a leading FAA ASSURE university providing drone-related research, an IPP team, Air Force/Department of Homeland Security drones based in state and a very supportive state legislature, governor and congressional delegation. They also have oil money and are willing to invest it into making North Dakota a leading drone state. North Dakota has the deep bench of expertise, the political will, and funding to quickly draft rules, test them, and get them passed in to state law.

ALASKA: Alaska has an FAA UAS Test Site, an ASSURE university, an IPP team, Army drones in state, and a supportive state legislature, governor and congressional delegation. Alaska is also the most aviation-friendly state in the Union given the large number of private and charter pilots in the state. It’s no wonder the first type-certified drones flew in Alaska and why DHS, Department of Interior, DOD and even the Canadian Armed Forces all turn to Alaska for drone advice. Like North Dakota, Alaska has a deep bench of expertise and deep pockets from its oil industry.

KANSAS: Kansas has an FAA UAS Test Site (under the Pan Pacific UAS Test Site), two ASSURE universities, an IPP team, a very large aerospace manufacturing presence, a state-wide drone certificate of authorization and a supportive legislature, governor and congressional delegation. Kansas doesn’t have the deep pockets of North Dakota, but they have the same deep bench of expertise. Kansas could make drone rules rapidly.

MISSISSIPPI: Mississippi has an FAA UAS Test Site (under the Pan Pacific UAS Test Site), a DHS UAS Test Site, houses ASSURE headquarters, has the Army National Guard’s only UAS Training Center, has three drone manufacturers along with an extremely supportive state legislature, governor and congressional delegation.

There are many more states that can make small drone rules safely and quickly. If you add up the states with DOD/DHS drones in state and involved with ASSURE, the FAA UAS Test Site program, the IPP and Pathfinder programs, it adds up to 27 states. That is more than enough states with a vested interest and the expertise to accelerate small drone rules. What do you think? Should Congress give them a shot at it?