Photo courtesy of Swiss Drones

For search and rescue (SAR) volunteers, the scenarios are seemingly endless. One mission could take them to the edge of a heavily wooded area, where they’re looking for a wandering Alzheimer’s patient, while another might lead them to a dangerous river where a local fisherman has gone missing. And of course there are the larger search efforts, where first responders work as quickly and safely as possible to find survivors after a devastating flood or other disaster.

These men and women must be prepared for just about anything, and that means arriving equipped with the right tools for the job. For a growing number of search and rescue organizations, that now includes unmanned aircraft systems (UAS).

While drones won’t replace more traditional search methods, such as ground crews and manned aircraft, they can certainly be used to fill in the gaps. They can, for example, cover larger areas than search parties on foot and reach tight spaces manned helicopters just can’t get to. UAS offer an economical, safe solution that helps save time—and in many of these situations, that could be the difference between life and death.

“This is a powerful tool for us whether we’re mapping a disaster pile to find victims or flying over a wooded area looking for a hiker or hunter,” said Christopher Boyer, executive director and COO of the National Association for Search and Rescue. “This is a big disruptive technology right now. Ten or 15 years ago it was GPS and cell phones, now it’s UAS systems.”

Search…

Down East Emergency Medicine Institute (DEEMI), located in Maine, often needs to perform searches in less than ideal weather conditions, Director of Operations Richard Bowie said, and there have been situations where heavy fog has kept his manned aircraft from getting to a scene. With a UAS, he can drive to the search area, launch the drone at 200 feet and get the images he needs. DEEMI was the first SAR organization to receive an exemption to fly a UAS in 2015.

The team also uses their UAS, which includes the DJI Inspire 1, to scope out an area before a more intense ground search, said Vinal Applebee, DEEMI section leader and chief UAV pilot. Before they send searchers to the scene, they determine the easiest, safest way to get there with the help of 3D modeling from DroneDeploy.

During the day, images and video are delivered to incident command in real time, Bowie said, giving searchers the ability to study the geo-tagged images live. If they spot something, they can send rescuers out to the exact location right away.

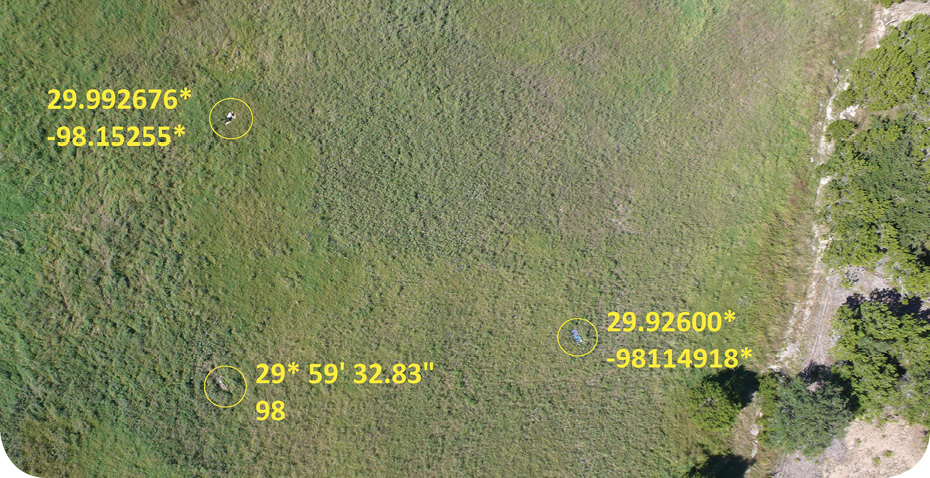

Gene Robinson, the founder of RP Flight Systems, uses the same process, and always has a ‘squinter’ on scene. This person sits in a quiet, controlled atmosphere looking at the images on a high-resolution monitor as the drone searches one square mile at a time; they quickly look at each quadrant before starting a more detailed analysis.

“If the squinter spots something, we send out two people to look at this one target instead of putting 50 people out in that one square mile,” Robinson said. “I would say that’s some resource management.”

And for the DEEMI team, the searching doesn’t stop when the sun goes down, Bowie said. The images collected throughout the day are uploaded to a server, where trained analysts in different parts of the country can access them. Overnight, multiple analysts carefully sort through the images looking for identifying objects, such as blue jeans or a bright colored coat.

“From our phone, we can also send live video to YouTube channels where analysts log in and watch the video as the drone is flying,” Bowie said. “You’re force multiplying your analysts to try to find the person.”

When trained properly, these squinters can find objects or clues helicopters missed, Robinson said. A few years ago, Robinson and his team were brought in to help find a missing 2-year-old boy. About 200 people from various organizations searched for the child for several days, but with no luck. The team deployed their drone on a foggy morning around 9 a.m., and before noon the squinter had spotted a red object that matched the mother’s description of the boy’s coat. That day, searchers were able to recover the child’s body from a lake not far from his home.

“That sort of impact is what keeps you going,” Robinson said. “The helicopter flew over that lake four times, but trying to maneuver around power lines and trees and other obstacles and dealing with vibration and people talking in their headsets—all while trying to look at everything in the process—is a difficult task. We’ve had a least three scenarios where a helicopter flew an area and didn’t find anything, then we went in with our aircraft and said, ‘What is that?’ Maybe you missed something.’”

Robinson is hoping software advancements will make it even easier to spot people based on what they’re wearing. If searchers know the person is wearing blue jeans, for example, they can tell the software to find anything in the picture that’s blue and a certain size, filtering out bigger objects like a lake. That capability isn’t available yet, but Robinson said it won’t be long until it is.

…and Rescue

When someone goes missing, chances are they might be hurt or dehydrated once rescuers find them. To help keep people alive until they can get to them, DEEMI also uses its drones to deliver supplies, such as medication and blankets, with the with the STORK Payload Deploy System for DJI Inspire 1.

The drop-offs are timed, Bowie said, and can be performed over and over.

“It’s a couple of stainless steel fingers attached to landing gear. When the gear goes up, the fingers separate and we can drop things,” Applebee said. “That’s very important in a rescue situation. Say somebody is stuck on a small island or maybe they capsized while white water rafting and are stuck on a rock without a life jacket. We can drop life jackets, water bottles, medical supplies and walkie talkies right into their hands.”

Delivering communication devices enables rescuers to talk to victims and find out how hurt they are and what supplies they might need, Boyer said. Adding a small speaker to a UAS could also help rescuers communicate with someone they haven’t located yet, using it to ask the person to come out of the woods or to wave his hands to make him easier to spot.

Larger Missions

While drones are great tools in the search for missing individuals, they also help first responders deal with disasters.

The Lone Star UAS Center of Excellence and Innovation at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi has flown UAS in flooding situations, the most recent being in response to the Blanco River flooding in Texas in the spring of 2016. The 43-foot flood surge scattered debris miles deep on each side of the river’s banks, said Jerry Hendrix, executive director of the center. Homes were destroyed and people were lost in the trees, building parts and other detritus carried by the water. Pilots in helicopters couldn’t see into the river and the debris made it nearly impossible for any sort of kayaker or powerboat operator to survey the flooded areas. Downed power lines and high water also made it a dangerous environment for rescuers. The drones were able to fly over areas no one else could get to, giving emergency personnel a more precise view of where someone might be.

Both fixed-wing and multi-rotor UAS can be used in these types of disasters, said Robin Murphy, director of the Center for Robot-Assisted Search and Rescue (CRASAR) at Texas A&M University, who responded to the Texas flood. Drones with vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) tend to be the easiest to deploy in these often harsh, rough-terrain environments and have the ability to hover and stare. Fixed-wings offer longer endurance and can cover larger areas. Each has its place in search and rescue, depending on the situation.

No matter what types of drones are used during a disaster—or ground or marine unmanned systems for that matter—these robots help speed up that initial reaction, which speeds up the recovery process and ultimately reduces the cost of the disaster, Murphy said.

“Everything is time dependent,” Murphy said. “With UAS, you need a system that lets you interrupt the path and go back to look at details to help you make decisions that could be life and death or that could save hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Artificial intelligence can be used to process the data drones collect more quickly and efficiently, Murphy said, which is key during disasters. During a recent flooding event, for example, the University of Maryland and the University of California Berkley developed algorithms to identify piles of debris that were the right shape and size to have people in them, helping direct responders to the right areas to search.

Basarnas, a search and rescue organization in Indonesia, recently began using Swiss Drones UAS to help locate missing people, said Dennis Menick, the firm’s sales and marketing director. They’ve used drones in a few missions so far, including a flood in Jakarta last September.

More than 20 people died during the event, and Basarnas operators flew the UAS to look for survivors as well as corpses in the water, Menick said. The durable drone has a two-hour flight time and can withstand high winds and harsh weather conditions, making it well suited for this type of work. The UAS flys with a gimbal that carries a high-definition camera and an infrared camera.

Typically, the team would fly a manned helicopter for this type of search and recovery effort, which Menick said is much more costly and dangerous than flying a drone.

“If you lose hardware, it’s so much better than losing a pilot or crew,” Menick said. “This is the beginning of a new era for them. They can use equipment that doesn’t risk their lives. They just fly it. They don’t have to fly a helicopter in a dangerous environment and worry about landing it in a small area.”

Trained to Help

Menick spent time training the Basarnas team at Swiss Drones’ headquarters in Switzerland and in Indonesia, and said this training was critical to ensuring the drone was operated safely and effectively. Flying these search and rescue missions—whether you’re looking for one person or several—isn’t something for untrained personnel or hobbyists who think they’re helping when they’re really not.

The fact that Part 107 requires operators to be certified is a positive when it comes to ensuring they know the rules of flying, but that doesn’t make them qualified to take part in SAR missions, Robinson said. Public safety has to be held to a higher standard, he said, which is why he’s developed a training program for search and rescue operators.

“I’ve been out on missions with people who don’t know what they’re doing and it becomes a hindrance,” Robinson said. “You don’t send a newbie out when a life is on the line.”

Dallas Griffin, managing member of Lone Star UAViators, also trains first responders on how to effectively use drones during these missions, and recently completed an exercise where rescuers were able to locate a target in seven minutes. While it would take rescuers much longer to find a missing person in a real life situation, the result of the demonstration does help show what UAS can do.

“We had someone wander into the woods and using applications such as DroneDeploy, which is what I use to fly a grid pattern, we took real time photos and looked at them on a larger screen,” Griffin said. “First responders could see exactly what the drone saw. Our telemetry shows heading, altitude, speed and direction from the base station, so they can focus their search on the specific area the drone went. It doesn’t waste a lot of time.”

Training for these situations doesn’t just come down to knowing how to operate the drone, though that’s important. Responders also have to be mentally prepared to handle what they’ll see in a disaster torn area, Hendrix said. Not only is it dangerous, there are a lot of frightened people who may have just lost their home or a loved one.

Responders also have to be prepared for the environment and be ready and willing to adjust, which might include finding new ways to launch and recover their systems, Hendrix said. They always have to be on the lookout for downed power lines and other dangers, and to come equipped with water and other supplies, such as snake bite and first aid kits.

“The most important thing is to be safe,” Hendrix said. “You don’t want to create a situation where you have to rescue the rescuers. Work in teams. Have radios and always use the buddy system.”

Of course drone operators must understand how to work with incident command, Hendrix said, and to only fly in areas they’re told to fly in. These scenes are often pretty chaotic, with manned aircraft part of the operations as well, making it vital to communicate and coordinate with other first responders.

Other Challenges

As more organizations deploy drones for SAR, they’ll have to find a way to safely integrate them into their rescue efforts. Darren Goodbar, UAS coordinator for Response Programs for the

Virginia Department of Emergency Management, is working to develop policies and procedures to define how third party volunteers and organizations can fit into the integration process.

In working with SAR organizations, it became clear to Goodbar that these experts are good at what they do, whether they handle K-9s or search on the ground. Giving them another task, such as operating a drone, takes them away from what they’re good at and could lead to inefficiencies. That’s where third parties, such as police, fire departments and UAS service providers come in, but then the question becomes what qualifications do those third party operators need to have.

“Can they operate effectively and know what’s going on in the incident command center and what’s going on in the response situation? Do they know how to integrate into incident command? Operators need to be familiar with all that,” Goodbar said. “We’re working with SAR experts on how to plug this into an organization that’s been around for 60 years. It’s not as easy as it would seem.”

Goodbar is also working with Robert Koester, CEO of dbS Productions and an expert in search theory, to determine at what altitude and speed drones are most effective for search and rescue. By plugging information into SAR software—data such as where the person was last seen and the drone’s sweep width value, that is the span covered by the drone’s sensors on each sweep—searchers can determine the best approach. This would incorporate the probability of where the subject has gone, a good flight path to cover those high-probability areas as well as those areas that are the quickest to search and eliminate. The drone’s operators can then follow the prioritized plan, performing flights at different altitudes and flight speeds for the best results.

“The major research objective right now is measuring that sweep width value for the various sensors you put on a UAS platform,” Koester said. “To optimize any resource one should have a sense of what the sensor can and cannot do and its abilities and limitations. What is the best camera altitude? What’s the best speed? If these factors are quantized then I can figure out the best way I can use this resource.”

The Future

The first responders Griffin works with are excited about the technology and how it can make search and rescue quicker, cheaper, safer and more effective. He sees fire departments, sheriff departments and SAR organizations investing in their own UAS for these missions, especially as regulations continue to become more defined and the cost of purchasing a drone comes down.

Already there are affordable options like the DJI Inspire 1, Bowie said, so it only costs a few thousand dollars to add UAS to the SAR tool chest. If they crash and break the drone during a mission it’s not a big deal; they can easily and economically find a replacement part or buy a brand new drone. This helps ensure they can fly the drone when the next mission comes up, safely surveying dangerous or out-of the-way areas they otherwise wouldn’t be able to get to.

“We’re trying to get to the person faster. We need to speed the process up because we’re trying to save a life,” Bowie said. “We’re trying to find them when they’re still floating down the river alive.”

Photos courtesy RPFlight Systems and the Center for Robot-Assisted Search and Rescue (CARSAR) at Texas A&M University.