The recently signed Farm Bill will dramatically boost funding for expanded broadband coverage in rural areas, where it is an essential ingredient for rapid processing of drone-based agricultural data. It also includes autonomous manufacturers on a new task force created to support the expansion.

Deep in the 500+ pages of the recently enacted Farm Bill is a significant expansion of the ongoing effort to build out broadband capability in rural areas. The money is still limited compared to the challenge, which is comparable to the building of the national interstate system. Even so, this early step could someday enable drone imaging with returns fast enough that diagnosing what ails a field will be more akin to taking its temperature than sending out lab work. Faster and more complete broadband coverage also has the potential to support a host of other applications, such as long-range rail and power line inspection.

The Farm Bill, known more formally as the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, authorizes $350 million per year to support and expand rural broadband. The Act increases spending for fiscal year 2019 through FY2023 by more than an order of magnitude over the $25 million per year authorized for FY08-FY18. The law also expands the Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) ability to provide that support in the form of grants as well as loans and loan guarantees. And it intentionally concentrates portions of the funding on the most sparsely populated areas—the sort of regions where drone-based assessment and, eventually, spraying could be particularly useful.

The total $1.75 billion boost in broadband funding is in addition to the $600 million in loans and grants available through the USDA’s recently launched ReConnect Program. Telecommunications companies, rural electric cooperatives and utilities, internet service providers and municipalities may apply for funding under the program to better serve rural areas that have insufficient broadband service.

TIMING IS EVERYTHING

High-capacity broadband is essential if farmers using unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) to diagnose problems with their crops are to get the results back fast enough to be useful. That means drone operators need to be able to upload the raw data for processing and get answers back in hours, not days.

“In agriculture it’s all about timing,” said Robert Blair, an active farmer at Blair Three Canyon Farms, in Kendrick, Idaho, and an expert on the use of drones for agricultural. “Twelve to 24 hours can be the difference between getting a treatment done on a crop or not.”

This is especially true if the problem in a field is insects or disease.

“Every day [a field is] left untreated you can start losing 1 to 5 percent of the crop,” Blair said, adding that quality problems also can develop.

The timing can be just as critical when putting down fertilizer. For example, said Blair, bad timing around the last rainstorm of the growing season can cost 10 bushels an acre of a wheat crop. That adds up to real money.

The price per bushel of soft white wheat was about $6.25 in his Pacific Northwest region in January 2019, he said. On a 500-acre farm that’s normally getting 100 bushels per acre, a 10 percent loss means a $31,000 cut in gross income.

To make the timing work,drone operators need to process data quickly. Ideally, that means loading it to the cloud as soon as a flight is complete. In many, if not most, rural areas, though, wireless service is not available at the necessary bandwidths or latency to handle the amounts of data involved.

“You can generate 50 to 60+ gigabytes of data, of imagery, in a day,” Blair said.

But if operators wait until they return to their office at the end of the day—or to a location that can upload large amounts on rural networks handily—they won’t achieve the necessary turnaround time.

“There’re still a lot of remote areas that don’t have good cell coverage and stuff. It’s really inconsistent,” said James Grimsley, a consulting contractor for the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, which is managing drone application research as the lead for one of 10 Integration Pilot Program teams for the Federal Aviation Administration’s UAS office. “So you may have a few towers, you go a little ways away and you don’t have anything at all. Likewise with the internet: There may be little pockets where there’s connectivity but basically it’s not consistent across agricultural areas—

especially where there’s large agricultural operations.”

Without high-speed communications, more complex drone applications may be impossible to do economically, Grimsley said. “A lot of people were really excited about agricultural use of UAS. AUVSI (the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International) said it was going to be 80 percent of the market. But what most people didn’t realize is that when you get in these rural areas it’s been very slow to bring broadband and communication infrastructure on.”

Grimsley called the broadband provisions the “biggest thing” in the Farm Bill, and not just because of what they could do for agricultural drones. “The next era of aviation, the next era of autonomous vehicles and driverless vehicles, all sorts of things and just general quality of life—high speed internet is going to be crucial for all of that.”

AT THE POLICY TABLE

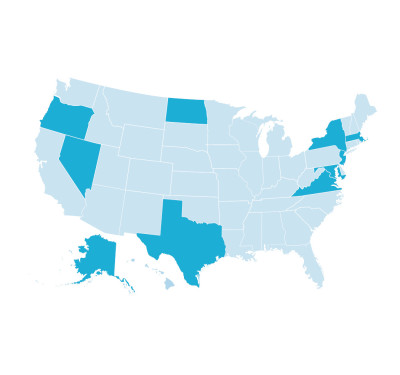

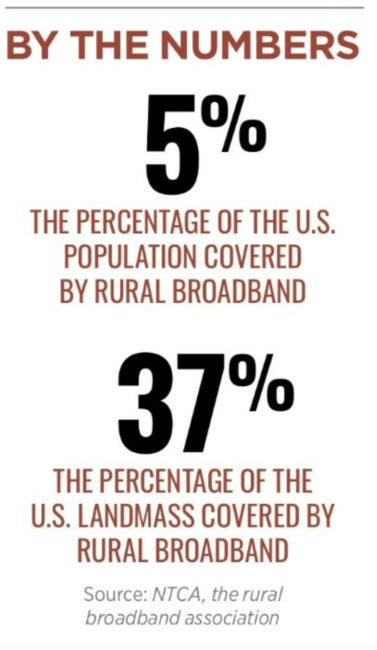

Though the new money is substantial, so is the extent of what needs to be done. To put that challenge into perspective, the members of NCTA, the rural broadband association, serve just 5 percent of the U.S. population but cover 37 percent of the U.S. landmass, said Joshua Seidemann, NTCA’s vice president for policy.

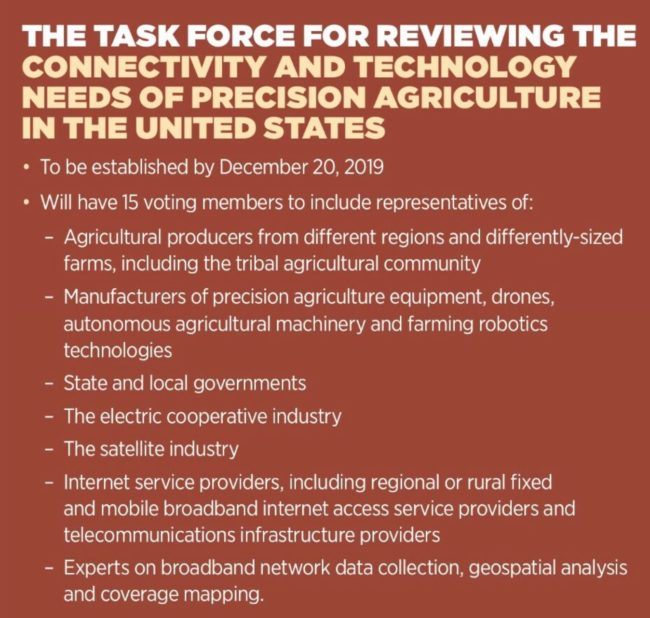

The good news is the Farm Bill is putting drone firms and other autonomous technology providers directly into the discussion about how to make it work.

The bill gives the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) until December 20, 2019 to establish a task force comprised of representatives of manufacturers of precision agriculture equipment, drones, autonomous agricultural machinery and farming robotics technologies. It also is to include agricultural producers from different regions and differently-sized farms, including the tribal agricultural community.

Additionally, there will be representatives from state and local governments, the electric cooperative industry, the satellite industry and internet service providers. The latter includes regional or rural fixed and mobile broadband internet access services and telecommunications infrastructure providers. The group, which is to number no more than 15 voting members, will be rounded out by experts on broadband network data collection, geospatial analysis and coverage mapping. The group is to be “fairly balanced” in terms of the technologies, fields and points of view, according to the bill.

Once in place the task force is to consult with the secretary of agriculture and collaborate with public and private stakeholders to identify and measure current gaps in broadband and internet access on agricultural land. Then they are to develop recommendations to promote the rapid, expanded deployment and adoption of service in unserved areas, “with a goal of achieving reliable capabilities on 95 percent of agricultural land in the United States by 2025.” To keep the ball rolling, they are to make recommendations to the FCC for new rules and amendments and more reliable data.

Technical and engineering questions remain to be solved, but the overall goal of expanding broadband coverage is doable, Seidemann believes. The boost in funding is a helpful and welcome injection of support and opportunity, he said, noting NCTA data showing rural broadband companies were already making real progress. Even so, more support will be needed over time. “Three hundred and fifty million dollars is not going to finish the job,” he said.