Christian Trotti is assistant director of Forward Defense in the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security at the Atlantic Council. The Washington, D.C.-based council is a non-partisan think tank that covers a variety of foreign policy issues, and Forward Defense specifically focuses on U.S. defense strategy, emerging technologies such as unmanned systems, and defense industry and acquisitions.

Q: What are the key ways uncrewed systems will affect the future of warfare?

A: What changes warfare is never one technology; it’s combinations of technology, and the concepts and training necessary to operationalize them. And imagination separates revolutionary change from evolutionary change. When you start combining those things, you see a future picture of warfare that is very different from what we see now.

Q: How do you see that difference?

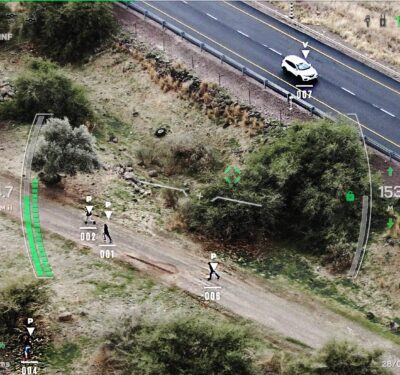

A: Increased mass, increased speed and increased fog of war. Particularly with unmanned systems, mass—large quantities of forces/systems from swarms of autonomous systems to even non-kinetic “fires” like cyberattacks—is going to be absolutely essential to the future battlefield. Speed, because unmanned systems will be making quick decisions with less and less human involvement over time. And then an increase in the fog of war—the proliferation of data means it’s going to be tougher to separate the signals from the chaff. Autonomy can help with that.

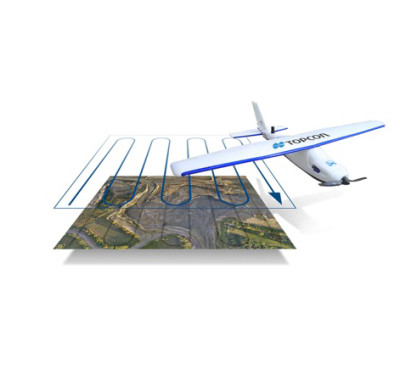

Q: In your writings, you see a sweet spot between quantity and quality, and a high-low mix. Why?

A: Legacy systems are very capable, but they will get hit, and will suffer. At a time when real spending is stagnating given inflation levels, autonomous systems can take on some human roles, freeing humans to do other things. A more cost-effective, cost-efficient force with more capabilities means the same investment in unmanned systems will allow us to serve multiple mission sets, achieving quality and quantity at the same time. By their sheer numbers, they’re designed to be attritable, and they’re cheap—it’s less of a loss of blood and treasure. That hits a sweet spot between capability and capacity, between quality and quantity. It gives us a real, real advantage.

Q: What lessons do you draw from the current conflict in Ukraine?

A: These systems, when used offensively, can blunt an adversary. The second one is “porcupine strategies”—to make our allies as tough to swallow as possible. It buys more time for us to come in with some of our more sophisticated legacy systems and platforms.

Q: Are there key barriers to overcome with autonomous deployment?

A: The first bucket is command and control, second is acquisition, and the third barrier is psychological. With the Predator and the Reaper, we have large teams dedicated to a single aircraft, which is the opposite of the saving potential of autonomous systems. We need to take the trust we have in the lower levels of the command structure and apply it to autonomous systems. Second is our acquisition mindset. Too often we end up with a very small number of very sophisticated platforms. We can’t let every system be the most exquisite; we’re just going to lose from a cost perspective. Third, we need to be comfortable with these systems making their own decisions. Some people were really nervouse about “Terminator-like” situations, but, honestly, already remotely piloted aircraft are often more discriminative than humans. It’s not about doing autonomy for the sake of autonomy. We need to figure out what autonomy is best suited to, deliver on ethics and eliminate some of those bureaucratic barriers to be able to compete by cost.