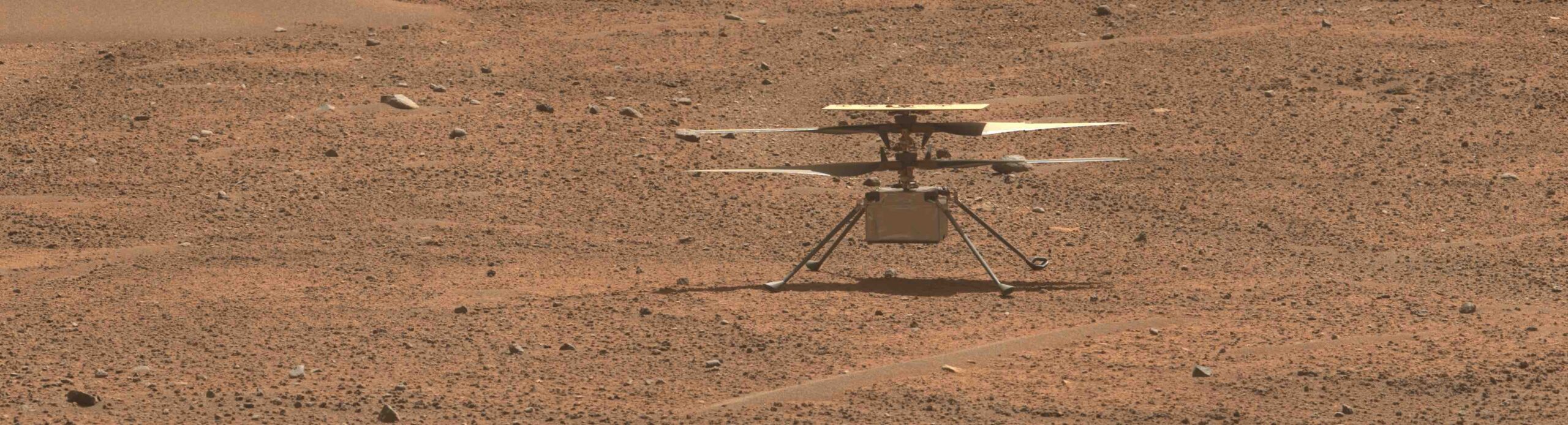

Two hundred seventeen or so million miles from Earth, Ingenuity rests motionless on the bleak Martian sand. One of the specially crafted rotor blades that’s provided the autonomous helicopter’s lift in the planet’s negligible atmosphere is bent after an abortive descent. Now only its shadow accompanies it.

“Bittersweet,” said Will Pomerantz, head of AeroVironment’s Space Ventures team, as he and I hoisted mid-afternoon coffee mugs in salute. True, Ingenuity had flown its last flight on January 18th. But with 72 flights, it had made history as the first powered off-planet flight, with far greater-than-expected endurance.

Ingenuity arrived on Mars on the underside of the sample-collecting Perseverance rover. No more than five brief technology demonstrations were envisioned for it in the thin, dusty atmosphere. But after a debut liftoff on April 21, 2021, it broadened its brief, becoming a scouting companion to the rover. A proposed 30-day deployment lasted a thousand or so days.

In a late January post-grounding press conference, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson celebrated the 48” x 19” by 20”, 4 Earth pound vehicle as “the little engine that could. It kept saying, ‘I think I can, I think I can.’ It has paved the way for future flights in our solar system.”

Pomerantz agreed. “It’s a little sad to think that it won’t fly again. But I think the overwhelming emotion reflected from the community is a sense of pride that this vehicle did so much more than we ever had the right to ask of it.

“I’d be lying if there was no sad element to it. But for the tech demonstrator mission, people came in sort of saying, ‘Hey, if it leaves the ground, we’ll be feeling great.’ We’re excited that we took a thing that nobody knew if it was possible and now, we’ve got 72 data points.” The Wright Brothers’ ushering in of the aviation age was invoked; appropriately, a small piece of the original biplane went along to Mars, celebrating a shared pioneering spirit.

Taking Flight

More than a decade ago, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory tapped AeroVironment’s experience with upper atmospheric flight to collaborate on what became the Mars Ingenuity Helicopter Program. JPL’s software,computing and visual navigation elements provided “the Mars part of the aircraft,” Pomerantz said, along with requirements from avionics to charging solar arrays. AeroVironment contributed a tiered arrangement of antennae, solar panels, blades, airframe and the like—“everything you can see externally.” Tests mirrored nearly all of what would be Ingenuity’s operational life: generating lift in an ultra-thin atmosphere, handling usually frigid but widely varying temperatures, having to spin rotors five to 10 times faster on Mars.

It would be a leap, as Ben Pipenberg, AeroVironment engineering lead for the project, previously told Inside Unmanned Systems. “There were doubts, even within NASA. The big challenge…is that you’re not setting a helicopter on the surface of Mars and then flying it. You’re really designing a small standalone spacecraft that also happens to fly.”

Partner concerns about diluting the mission arose—what Pomerantz described as “you’re a hitchhiker; your job is to not mess with the rover.” AeroVironment tested multiple models and dealt with learning curves. “There are not a whole lot of helicopters that can go several years without any without any maintenance, inspection,” Pomerantz said. But collaboration proved vital, and champions emerged. “JPL would call and check things out and tap into our expertise. For operational cadence and usage and flight software, he added, “the credit should go to the wonderful team at JPL.”

“Every future vehicle that leaves the surface of Mars or another world and flies under power, you’re going to be able to trace its DNA right back to it.”

Will Pomerantz, head of Space Ventures, AeroVironment.

And so, Ingenuity rode along when an Atlas V rocket thundered off Earth on July 30, 2020. Over nearly three years on Mars, this “ride-along hitchhiker” expanded beyond technology demonstration as JPL sent increasingly ambitious maneuvers that Perseverance could pass on for relatively autonomous scouting. Missions over stark craters. Altitudes increasing from just above the surface to a relatively panoramic near-80 feet. Several workarounds kept Ingenuity going past temporarily lost signals. The mission stretched to 14 times the original expectation, with Ingenuity’s solar power surviving a Martian winter. Data flowed.

The end came not with Ingenuity crashing into a promontory but with what seems to have been an inability to locate landmarks over a barren landscape. Flight 71 got lost and set down, disoriented. After almost two weeks, Flight 72 popped up to about 40 feet, hovered, then apparently lost contact with the rover about 3 feet above the ground.

The Future is Now

“Every future vehicle that leaves the surface of Mars or another world and flies under power, you’re going to be able to trace its DNA right back,” Pomerantz said about Ingenuity.

Pomerantz joined AeroVironment full-time last Fall, but his adjacencies include commercial space work and training as a Martian geologist. Ironically, his wife was JPL’s flight director for Perseverance on the day it first deployed Ingenuity. His hire signifies a corporate commitment to a new business unit built around the Ingenuity team.

Pomerantz traced the unit’s possible flight path. “Even before Ingenuity had been deployed on the surface of Mars, we were already thinking pretty hard about what might come next. There are things we will do differently next time around, elements we didn’t put into the program because we weren’t thinking about how to make it most impactful on Flight Number 73; you were thinking about how to get to Flight Number One.

“A big part of that is just the difference of planning for an operational mission versus a technology demonstrator. The vehicle, which was state of the art in a lot of ways, was very much not state of the art in some other ways. We really weren’t optimizing for a high degree of autonomy, to make the vehicle as robust as possible. It wasn’t carrying a bunch of science instruments because that wasn’t the goal of the mission.

“What was learned was that this small, low-mass inexpensive-on-the-scale-of-Mars vehicle could be such a wonderful partner for this flagship rover, exploring terrain where the ground vehicle might get stuck in the sand, or a steep slope, doing the most ambitious science they can without exposing the rover to undue technical risk.”

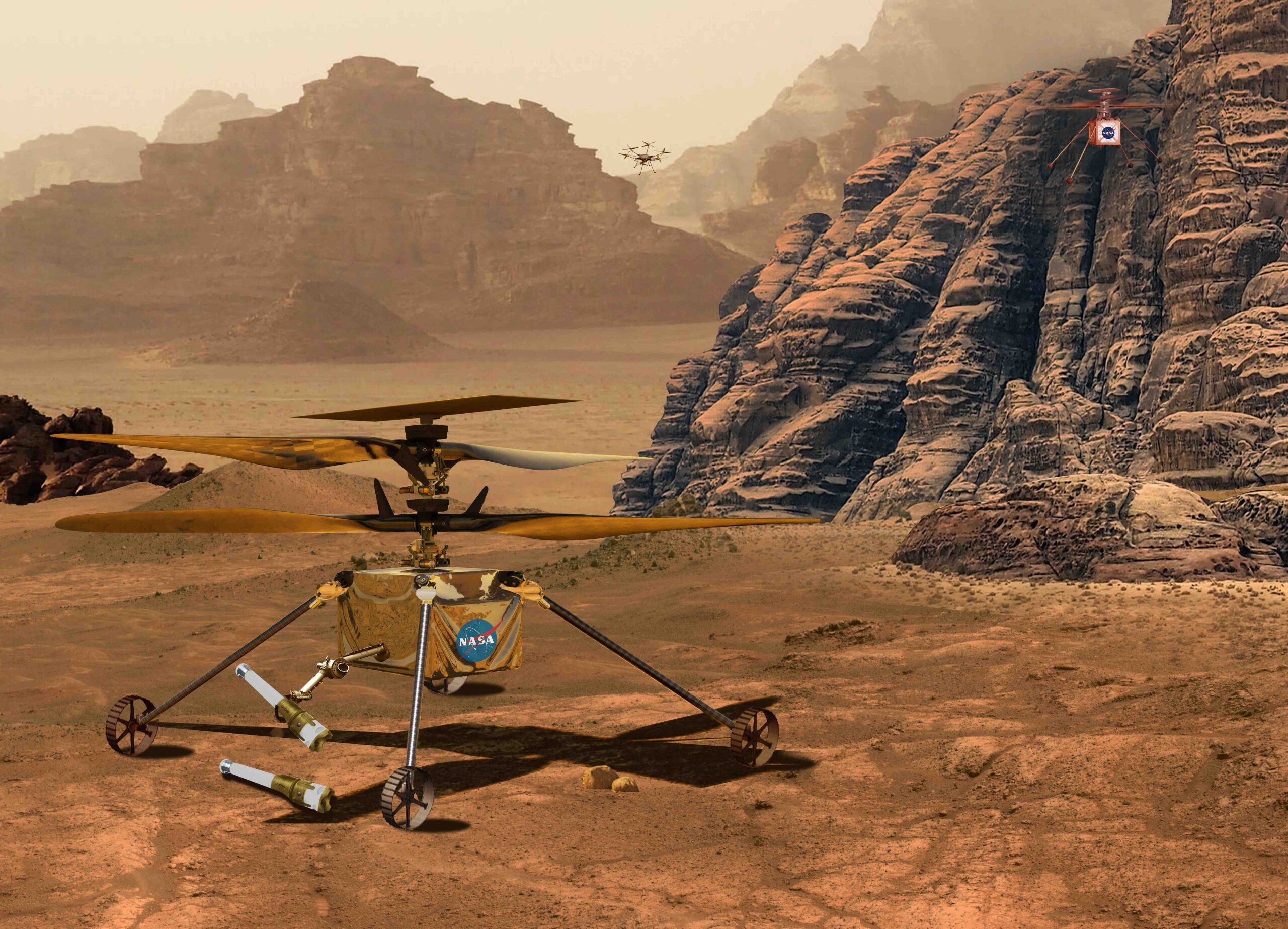

Ingenuity was AeroVironment’s first space project, but others are planned. “As ‘Ingenuity 2.0,’ ‘the child,’ whatever you want to call it, how much faster can it fly? How far can it fly and all at latitudes, in all seasons?” There’s instrumentation for new tasks; possibly attached arms or its own set of wheels; greater volume; new materials, designs and fabrications. More autonomy.

Pomerantz’ team is on call to deliver two Ingenuity-like Sample Retriever Helicopters as part of NASA’s and the European Space Agency’s Mars Sample Return program, in which a robotic dual-quad rotorcraft would deliver rover-collected samples for transport back to Earth. There’s also “a small part to play” with Dragonfly, which is slated to look for signs of life on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. “We’re looking at missions of our own and talking to other parts of the exploration community.”

As we closed with another non-alcoholic toast, Pomerantz noted that Ingenuity’s mission wasn’t quite over. While the ship can’t fly, it was sending data for post-mortem analysis.

“It can still phone home.”