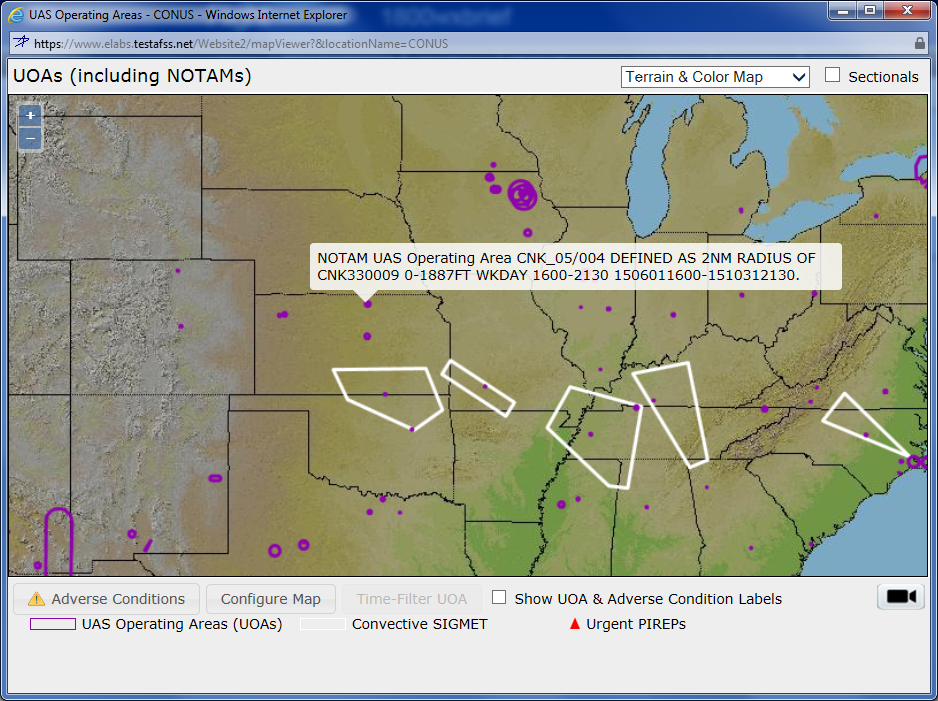

The maps anyone can look at to see where UAS operations are active or planned.

As more unmanned aircraft take to the skies, it’s important that pilots know where these aircraft are operating.

Lockheed Martin is working to design a UAS traffic management system to help keep pilots and operators safe as they fly in the National Airspace. The first components of the system were recently deployed through the Lockheed Martin Flight Service Pilot Portal, with more expected in the coming months.

The company is collaborating with various industry stakeholders to develop these UTM capabilities, including the NASA UTM research project through a Space Act information sharing agreement.

“The foundational capabilities we’re developing are about safety, efficiency and situational awareness,” program subject matter expert Heidi Williams said. “Our capabilities are addressing those needs first. As UTM evolves, we can build on that foundational set of capabilities, and we’re more than prepared to do that.”

Here’s a look at the UAS-related capabilities the portal already offers, and enhancements you can expect to see in the near future.

The Portal

The Flight Service Pilot Portal initially launched for the FAA and served as a place for pilots to plan their flights either over the phone or online, said Mike Glasgow, Chief Architect and Lockheed Martin Fellow. The website, 1800wxbrief.com, launched in 2012 and gives pilots the ability to go online and find out everything they need to know before flying. This serves as a good infrastructure to communicate with pilots about drone activity as well.

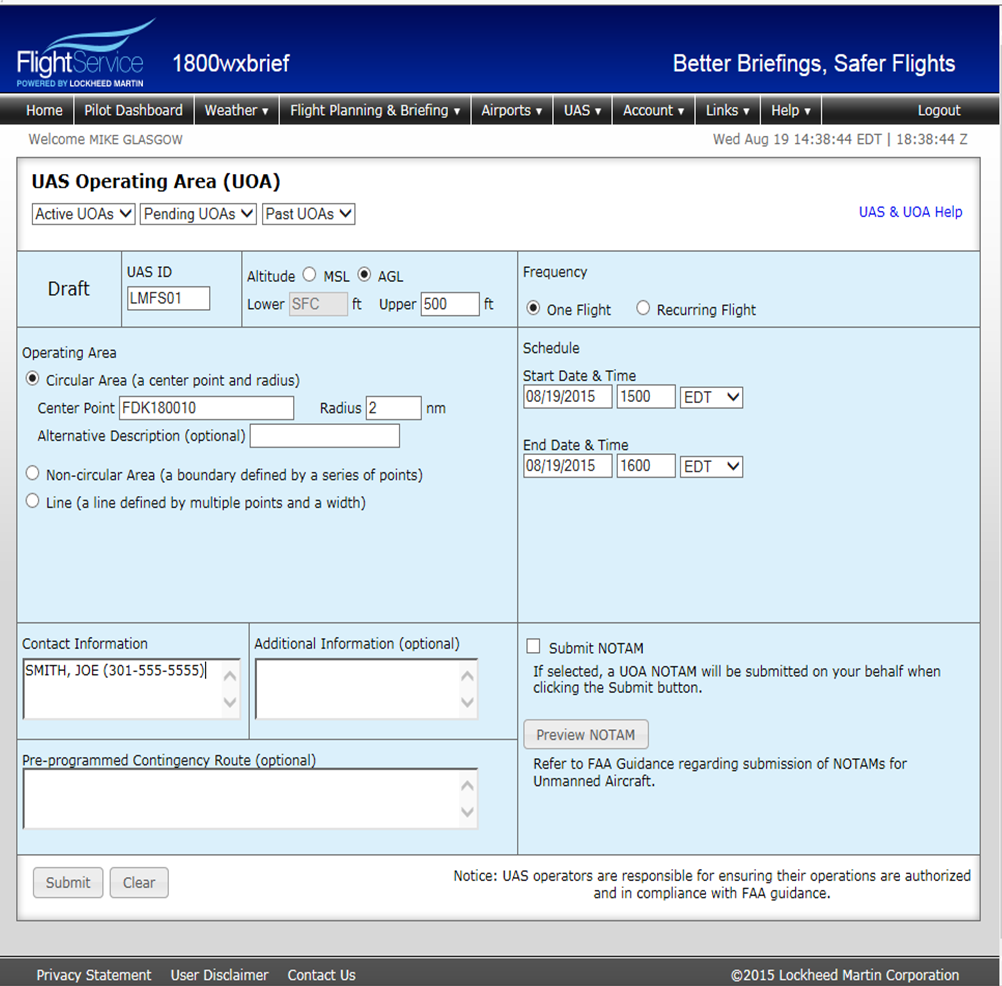

The form used to file a UAS operating area.

How it’s Working for UAS

When UAS operators receive a Certificate of Authorization to fly, they have to file a Notice to Airmen, or NOTAM, for each flight to let other pilots know the UAS will be in the airspace, Glasgow said. The team at Lockheed Martin can file those NOTAMs for operators over the phone, and UAS operators will soon have the ability to file them online through the portal, once that function is approved by the FAA.

Once the operator is in the system, the next step is creating situational awareness for pilots who use the flight service, Glasgow said. They use three methods to notify them of UAS operations: a map, a briefing and an alerting service.

Via the map, operators can use the UAS tab to see where drones are scheduled to fly in the continental U.S., Hawaii and Alaska, Glasgow said, and can zoom in and click on each scheduled flight to get more details.

“It’s a planning tool that helps pilots know right away what will be in the area they’re intending to fly in,” Glasgow said. “As we develop this we are in constant dialogue with the test sites and the FAA. We continue to get input into other things pilots would like to see. Through the map you not only can you see where UAS operations are, but you can also see adverse conditions and severe weather flight restrictions.”

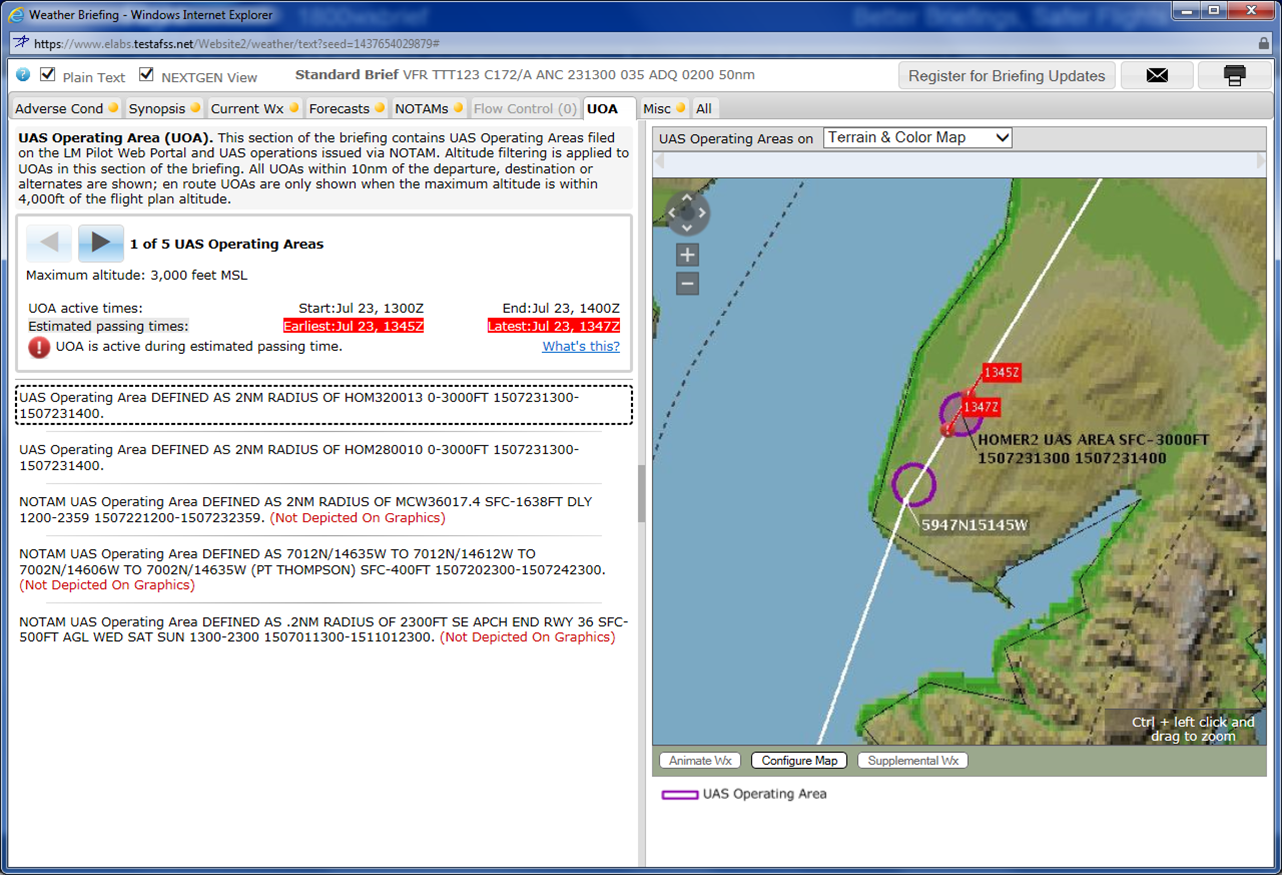

The briefings are what Glasgow describes as the bread and butter of the flight services. Instead of sending pilots a blob of text with information outlining the area specified by the NOTAM—which is difficult for both the pilot and the flight services specialist to visualize—they receive a graphic that shows the pilot’s flight route.

Through the NextGen Briefing capability, or NGB, pilots can also see if any UAS operating areas are intersecting their flight path, and when their manned aircraft will enter those areas. In the summary box, pilots can see how long they have to pass through the area before the UAS is active, or if they’ll be in the area at the same time as the UAS.

Finally, the system also provides pilots with an alerting service, Glasgow said. If something changes with the weather or if a UAS is spotted in the area they’re planning to fly after they were given the briefing, they receive an alert either through an email or a text message.

“It continues to monitor the flight in the background,” Glasgow said. “If a new condition pops up, it sends an alert. The alert has a picture and can be satellite communicated directly to the cockpit. We’re adding UAS operation areas to that. It’s anything that represents a hazard to a pilot. So they get maps, they get a briefing and we have an alert service.”

What’s Next

The team is working on developing an app that will serve as the ground control station for UAS, but will run on an iPad instead of through the website. All operators will have to do is push a button to submit, making it more convenient to flight plan. Glasgow expects that feature to be available in the next few months.

Flight services will also provide support for exemption cases, Glasgow said, which happens when a UAS is flying in an area it’s not intended to fly in. They’ll support two situations. The first is known as a fly away, when a UAS goes beyond the range of the radio control link and doesn’t have the ability to return to base. The second situation is nonconformance, when a UAS enters a geo-fenced airspace. Both situations present potential hazards to pilots, and flight services specialists will determine if it’s something air traffic control needs to know about. Pilots will also receive alerts about these situations.

When an exemption case occurs, people will be able to call flight services or report the incident through the website. This feature should be functional by the first quarter of next year.

The team is also looking at taking position reports for unmanned and manned flights and performing ground based detect and avoid, Glasgow said. The capability would allow them to see when two aircraft are getting too close to one another and notify them they need to move. That is the building blocks for beyond line of sight applications for UAS, Glasgow said, and is one of the longer-term capabilities the team is working to develop.

How the flight service shows UAS operating areas to pilots in a briefing.

The Challenges

The fact that the FAA is still working on determining regulations for UAS makes developing UTM capabilities challenging, so Glasgow and his team are focused on creating components they’re confident will be needed, no matter what the final rules are.

“It’s kind of a balancing act,” Glasgow said. “As an industry and community we’re still trying to get all the rules and policies in place for how this will work. Deciding what capabilities make sense to deploy now when we don’t have rules is a significant challenge. We don’t want to get ahead of the FAA. We’re in constant collaboration with them.”

As the industry tackles the many unknowns, Glasgow and his team will continue to develop capabilities that will work no matter what solutions end up being deployed, and no matter the size of the UAS.

“We don’t care if they’re large or small. Any of them can use the system. We expect different users to use different subsets of the capabilities, depending on what their needs and requirements are,” Glasgow said. “This is all about safety. Keeping pilots aware of aircraft operations is fundamentally a safety issue.”