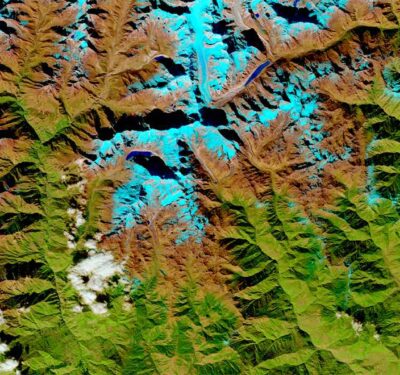

Boeing conducts an MQ-25 Stingray deck-handling demonstration at its St. Louis facility.

Last month the U.S. Navy reached a major milestone toward its “game-changing” goal of fielding carrier-based aerial refueling drones, flight-testing a Boeing T1 prototype fitted with the same aerial refueling system (ARS) used by the Navy’s F/A-18 Super Hornets.

The prototype is being used to develop the MQ-25 Stingray, a refueling tanker drone the Navy says will be the world’s first aircraft carrier-based UAV. But it’s so advanced the Navy doesn’t yet have pilots who can fly it.

To find them, the Navy has announced a major effort to recruit and train a new generation of UAV operators with skills not seen before.

“This is an exciting new chapter in the storied history of naval aviation,” said Chief of Naval Personnel Vice Admiral John Nowell in a release announcing the plan.

Refueling aircraft are considered “force multipliers” because they expand the combat radius of attack, allow patrol aircraft to remain airborne longer and enable aircraft to carry heavier payloads. But aerial refueling is a perilous task.

In 2017, six marines were killed off the coast of Japan during an aerial refueling training exercise and last September a Marine Corps F-35 crashed in California after clipping the wing of a Marine KC-130 refueling tanker. A UAV could reduce human risk factors that cause such accidents.

The Navy will pay Boeing as much as $14 billion to build 72 Stingrays, plus millions more to design complete UAV systems that integrate with the carrier fleet’s existing network and communications infrastructure.

Technically speaking, the Stingray will be a beast. Capable of carrying 15,000 pounds of fuel with a range of 500 nautical miles, it will be powered by a variant of the Rolls-Royce AE 3007N turbofan engine used by the Navy’s MQ-4C Triton UAV that can deliver 10,000 pounds of thrust.

The need for training is manifest. Operators will have to pilot the Stingray at jet fighter speeds from hundreds of miles away in perfect unison with the receiving aircraft. The UAV must also seamlessly integrate with manned aircraft as it shares the ship’s deck, airspace, and catapult launch and recovery systems.

Moreover, the Navy might also leverage the long-range and high payload capacity by giving it intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities. All told, these complexities “require specialists rather than pilots from other type-model series,“ Nowell said.

Navy officials want to recruit, train and deploy some 450 Stingray pilots during the next 6 to 10 years. To find the best and brightest, they have taken the unusual move of creating a new warrant officer specialty. Unlike traditional Navy chief warrant officers, who move up from the enlisted ranks, Stingray operators will primarily be recruited at a younger age from the civilian population.

Those selected will attend officer candidate school and complete 18 months of specialized training, forming a knowledge base that will help increase the Navy’s footprint in other next-generation UAVs too. After their first Stingray sea duty some pilots could also operate the MQ-4C Triton maritime surveillance drone while on shore duty.

The Navy plans to deploy the MQ-25 in 2024, but some select Navy aviators are already learning how to pilot it.

Days before the recent experiment, four Navy air vehicle operators from VX-23, the Navy’s developmental test squadron, and VX-1, the operational test squadron, attended a three-day training simulation at Boeing’s St. Louis facility. There they learned to pilot the UAV from takeoff to landing while inside the ground control station.

Lt. Venus Savage, the VX-1 MQ-25 assistant operational test director, said the training was a unique opportunity to learn from Boeing pilots about the command and control processes used to interface with and operate the MQ-25 long before it’s delivered to the Navy.

“Especially for operational tests, we’re lucky to be involved this early in the program,” Savage said. “It helps when you get that side information from an experienced AVO [aerial vehicle operator] that adds to what’s in the documentation.

“We were able to ask detailed questions and get clarification on what the checklists and commands are, and they let us know what to expect from the air vehicle. It helps ingrain it in your memory because it’s more than just book learning.”

The Navy plans to begin accepting applications for the Stingray operator program in the first quarter of fiscal year 2022.

Photo credit: The Boeing Company.