Multiple developments across multiple domains are blending scalability and high technology to counter peer and near-peer threats.

At this September’s Central Coast AirFest, Mustangs, Warthogs and Hornets buzzed the clear California sky. But thoughts turned to what a future show might look like, featuring Stingrays and undersea Manta Rays, LongShots and Switchblades.

FROM PLANES OF FAME TO DRONES OF FAME?

A roster of unmanned warfighting programs and initiatives reveals a confluence of factors spurring this shift. Ukraine-Russia is the first unmanned versus unmanned war, where behemoth tanks scurry and retreat to avoid being blown to bits. Rising concerns around Indo-Pacific hegemony include the risk of carrier groups facing potential vulnerability. Topline systems cost a fortune.

And so, the DOD is adopting a two-pronged approach: all-domain attritable systems under programs such as its Replicator initiative to accelerate adoption of mass, scalable weapons while also supporting high-tech concepts that can secure dominance. “We still need the full suite of U.S. capabilities that we’ve invested in to remain combat-credible,” said Aditi Kumar, deputy director, strategy, policy & national security partnerships at DIU, the Defense Innovation Unit.

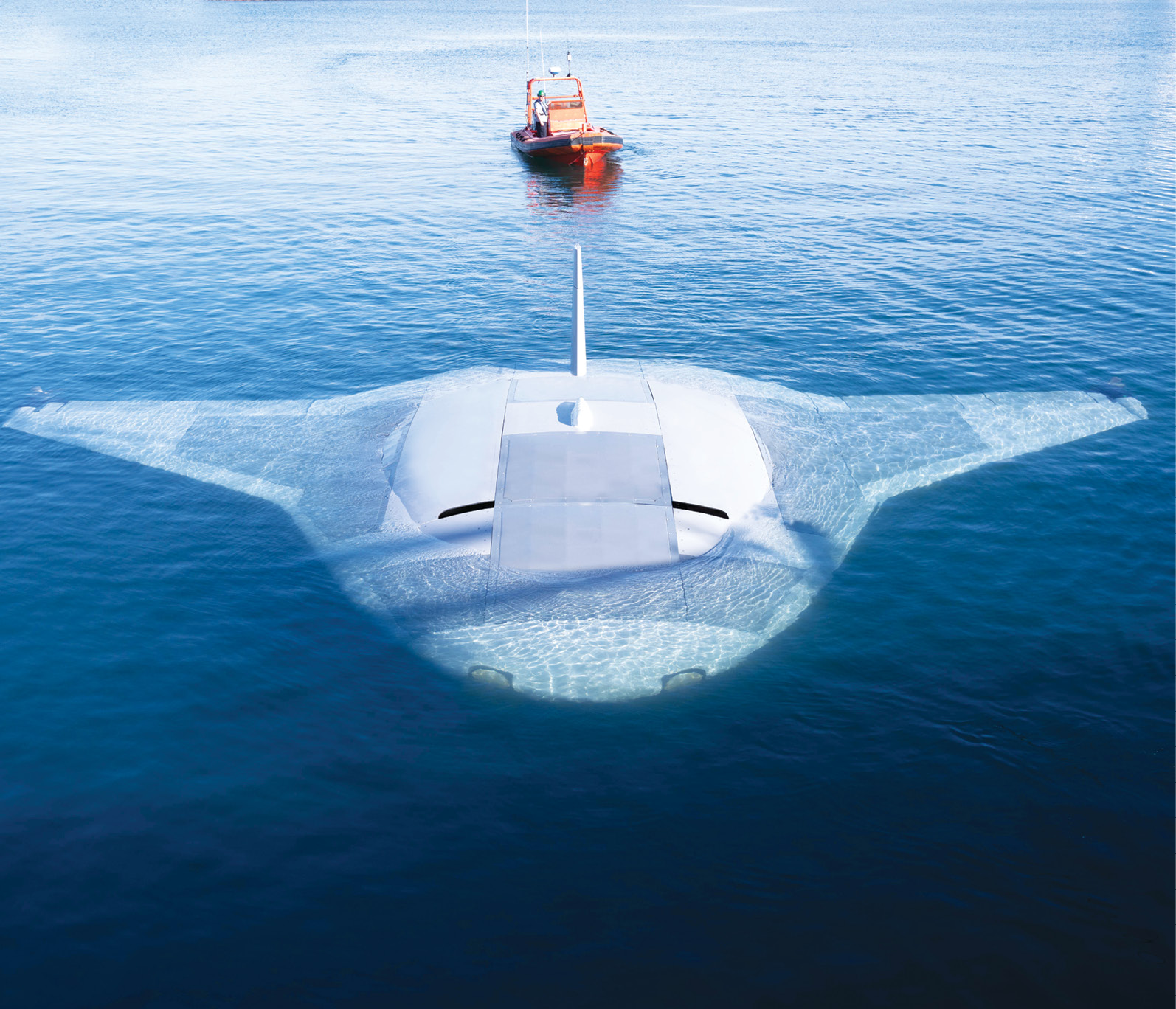

MANTA RAY: GLIDING UNDERSEA

With its lifting body blending into a 45-foot wingspan, Northrop Grumman’s Manta Ray looks like something Captain Nemo would worry about on his fictional Nautilus submarine. The extra-large unmanned underwater vehicle—XLUUV—is one of several submersibles out to thwart Chinese ambitions in the Pacific even as that country researches similar vehicles.

Manta Ray began with DARPA’s 2020 RFP for a new class of underwater vehicle capable of long range and duration. Advancements in energy management, efficiency and power were among the criteria called for. Such a ship had to deal with both oceanic rigor and the ability to operate far from port.

Northrop Grumman’s long history with unusually shaped vehicles dates back to its N-1M flying wing planes of 1940, and that provenance has been realized in the U.S. Air Force’s B-2 Spirit and current B-21 Raider. Here it’s coupled that learning with decades of research into underwater, long-range gliders.

“The program utilized model-based engineering to design and build the vehicle, with 3D digital models versus traditional 2D drawings,” Joseph Deane, program manager, Manta Ray, Northrop Grumman, said. “We developed concepts of employment and operations in immersive virtual reality, allowing us to evaluate threats and create solutions with the customer.”

“Manta Ray’s glider shape and advanced buoyance engines save power and energy, making the UUV able to go on longer missions. Its unique blended wing design permits power-efficient gliding, which allows the vehicle the range to explore vast areas of the ocean,” Deane said. “The design goal is to be completely autonomous, with little human interaction.” Payload bays of various size and type enable a wide variety of mission sets and provide endurance.

Over this past February and March, Manta Ray completed tests off Southern California that involved gliding, propellers, control surfaces and steering—and ascent and descent by pumping or expelling seawater. “During in-water testing,” Deane said, “we demonstrated some of the skills autonomously, which provide the building blocks to enable Manta Ray to operate on long-duration missions and communicate critical data back to remotely located human supervision.” The vehicle is envisioned to “hibernate” until needed, further saving energy.

The exercise also demonstrated the value of Manta Ray’s modular construction, which allowed Northrop Grumman to move it in standard shipping containers from coast to coast.

Northrop Grumman is not the only company involved in autonomous submersibles. Martin Defense Group (now PacMar Technologies) is involved in the Manta Ray program and is also building and testing its own prototype. Boeing’s Orca can run to 81 feet with an inserted mission-adaptable payload; its first prototype was delivered to the Navy last December. And the Navy is using Defense Innovation Unit funds for an initial buy of Anduril’s Dive-LD, with its potential for survey, inspection and ISR.

STINGRAY: EXTENDING CARRIER RANGE

John Scudi’s 27-year naval career included a stint flying fighters. Now, he serves as business development and acting MQ-25 Advanced Capabilities program manager for Boeing’s unmanned MQ-25 Stingray program. “It’s going to be a busier business in the next 20 years than in the last 20,” he said about the evolution of unmanned weaponry.

Contracted in 2018, Stingray couples Boeing’s air vehicle with a mission control integrator from Lockheed Martin. Targeted for deployment in 2027, the MQ-25 Stingray would be the world’s first operational carrier-based unmanned aircraft. As a 500-nautical-mile range tanker carrying 15,000 pounds of fuel, it could extend the reach of U.S. Navy carriers and combat aircraft, minimizing their threat exposure. Stingray also fits the DOD’s concept of manned-unmanned teaming (MUM-T).

To get there, though, Stingray has to match some key performance parameters around tanking and being integrated onto an aircraft carrier. In 2021, a T1 test asset was demonstrated aboard the USS George H. W. Bush, which itself was given an updated ground control station and control system. “We gave gas to F-35s, F/A-18 Super Hornets and [early warning E-2] Hawkeyes. After some production challenges, one MQ-25 is in static testing; five more are ‘in flow,’” Jackson said. Supported by a new factory, flight testing and reaching unique carrier qualifications around catapults and automatic landing systems, the program would be declared IOC—initial operating capability; extended capabilities also could allow Stingray to refuel Air Force planes, and to itself be refueled by KC-46 tankers. Additionally, a Stingray armed with Long Range Anti-Surface Missiles was shown at a conference this April.

At 51 feet, Stingray is as long as an F/A-18; its 75-foot wingspan matches that of an E-2. “This is a big vehicle,” Scudi allowed. “How many can you fit and still have a strike capability?” At the same time, Stingray would allow F/A-18s that have been pressed into tanker service to again become strike fighters.

Jackson noted the Navy’s active collaboration as Stingray moves forward. After several phases of low-rate production, 76 aircraft costing $13 billion or more are envisioned—pending continued program success and budget approvals.

“More important than just giving gas,” Scudi said, “this program is laying the foundation for the Navy’s autonomous path forward, when manned aircraft won’t have to do dirty, dangerous or boring missions or unmanned aircraft can complement manned aircraft in a contested environment.”

LONGSHOT: AIR COMBAT DISRUPTOR

DARPA—The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—is known for incubating military technology for the Department of Defense. Its LongShot disruptive air concept drone seeks to empower manned-unmanned teaming and loyal wingman approaches, being launched from existing aircraft to enter air combat with a range of air-to-air weapons, or to serve as decoys.

“LongShot is a technology demonstrator program intended to showcase the ability of air-launched uncrewed air vehicles to employ existing air-to-air weapons,” a DARPA spokesperson said. The sleek, rear-engine technology demonstrator could extend engagement range and the effectiveness of fourth-generation fighters, reduce risk to crewed platforms and leverage existing weapons, aims that fit the DOD’s Replicator initiative’s desire for scalable, affordable and potent technologies.

In 2023, General Atomics Aeronautical Systems received a solo contract for Phase 3 of a 2020 contract to develop DARPA’s concept. “The testing will validate basic vehicle handling characteristics and lay the foundation for follow-on development and testing,” General Atomics posted. The DARPA spokesperson provided an update: “Wind tunnel testing will occur over the next several months to characterize air vehicle flight surface deployment and free-flight aerodynamic performance.”

DARPA’s FY25 budget request includes funding for the program, with flight testing expected to commence in the second half of the 2025 calendar year. DARPA has a checklist of things to verify: safe separation from the host platform, transmission from aircraft store to flying vehicle, the stability of and control challenges of launching air-to-air missiles from a relatively small air vehicle in an operational environment.

“DARPA is engaged with USAF and USN stakeholders,” the spokesperson said, “to keep them apprised of program progress as we look to transition LongShot’s enabling technologies.”

SRR: PLATOON-LEVEL RECON

U.S. soldiers in contested battle zones need rapid intel. Enter the Short Range Reconnaissance program, which seeks to equip platoon-level units with small, rapidly deployed drones that can conduct near-range recon and surveillance.

SRR requirements were first voiced in 2013, and the program of record began in 2018. Thirty-seven companies responded to the RPF, vying to meet benchmarks for tech-intensive autonomy, interoperability and module-swapping. Realizing a shift toward defense, Skydio became the SRR solution provider of record in November 2021. “Tranche 1 is currently being fielded with something over 800 systems delivered to units,” an Army spokesman told Inside Unmanned Systems.

About nine months ago, the ongoing competition narrowed to two vendors: Skydio and Red Cat/Teal Drones. A next-step Tranche 2 announcement is said to be imminent.

Skydio’s newer X10D combines maneuverability with technology such as FLIR’s high-end thermal imaging sensors and NightSense, software that enables obstacle avoidance in zero-light environments. In June, Skydio won a $20 million contract from the Army.

Over this year, Red Cat, which purchased Teal Drones three years ago, has put forward an interoperable military drone family that includes a long-range fixed-wing VTOL, a smaller FPV drone—and a new SRR nominee submitted to the Army for testing and evaluation. Red Cat has drawn in partners, including for swarming capabilities. And, like Skydio, it has increased its nighttime flyability, under the slogan “Dominate the Night.”

“SSR Tranche 2 has not yet been announced so we just don’t have a lot to say at this point,” a Skydio spokesperson replied after several requests for comment. Over at Red Cat, CTO George Matus (formerly CEO of then-standalone Teal Drones), offered some historical and program-related perspective.

With DJI’s rise in the commercial market in the mid-2000s, he said, “things were very difficult for us and the rest of the industry as well. But that is when the Army banned DJI and created this SRR program to field a trusted alternative that is cybersecure, that is not dependent on Chinese supply chains, that is ideally made in America and gives warfighters the tools they need to be successful on the battlefield.

“This program is quite interesting because it reflects a desire from the government to iterate faster and procure technology faster so they’re not locking into a single vendor for forever,” he continued. “The intent with SSR was to refresh the competition, and so they created Tranches.

“We weren’t ready for prime time during Tranche 1,” Matus confessed. “But Tranche 2 gave us a new opportunity, a new set of requirements that will be impactful on the front lines. We were acquired by Red Cat and we invested over the last three years north of $70 million. And we’ve built something special that we’re going to announce later this year.”

Matus emphasized the significance of drone technology. “You see how impactful drones are on the front line. It’s like the introduction of the machine gun 100 years ago. We need to install next-generation technology from the seabed to the heavens.”

REPLICATOR: ATTRITABLE CAPABILITIES

In August 2023, sparked by a desire to incorporate lessons learned from the Ukraine-Russian war, the DOD announced the Replicator initiative as a way to accelerate delivery of innovative all-domain technologies at speed and scale. The on-track goal: “to field multiple thousands of systems on or before August 2025,” said Aditi Kumar, director, strategy, policy & national security partnerships at DIU. Kumar explicitly identified the goals: “to counter the PRC’s military mass” and to identify “best practices and processes that are replicable and being applied to address a second, different operational gap.

“The initiative is purposefully designed to overcome challenges faced by commercial partners inside and outside the department,” Kumar said. Replicator, she added, is about mobilizing the speed and creativity of commercial and dual use partners “to ultimately acquire ‘ready to scale’ capabilities on accelerated timelines.”

Specifically, Replicator I, the initiative’s first iteration, seeks to provide what’s known as ADA2—all-domain attritable autonomous systems—at scale. These systems could spark cutting-edge technologies while building production capacity and “creating meaningful incentives for the commercial sector to continue to innovate to keep pace with evolving threats.”

“Non-traditional defense companies play an essential role in the sUSV interceptor effort,” DIU Director Doug Beck has said.

The first group includes uncrewed aerial, surface and counter-uncrewed systems. This August, contracts were awarded to a mix of mid-size, non-traditional and venture-backed companies to prototype small unmanned surface vehicles in partnership with the Navy. Subsequent initiatives, Kumar said, will deliver “successive portfolios of capabilities” and further the National Defense Strategy with lessons on how to break down systemic barriers and ‘replicating’ successes with each iteration.”

The initiative is declaring success. Speaking at NDIA’s Emerging Technology for Defense conference this August, Deputy Security of Defense Kathleen Hicks, who has been something of the initiative’s sparkplug, said “what we’ve done in under 12 months can take seven to 10 years for similar-sized capabilities”.

That said, some turbulence emerged in October 2023 as Congressmen and industry observers attending the House Armed Services Committee’s Subcommitee on Cyber, Information Technologies and Innovation called for more details about goals, timelines and cross-system communication.

“We’ve done nearly 40 Hill briefings of Replicator since last October,” Kumar countered, “as well as consulted with a number of advisors and experts to identify barriers and solutions to scale and acceleration. Congress shares our commitment to defense innovation and has shown this by approving $500 million of Replicator funding in one year. We could not execute Replicator without their partnership.”

Those companies went mostly unnamed. “We are only selectively revealing systems for security reasons. One system we have highlighted is the Switchblade 600. Switchblade drones have already demonstrated their utility in Ukraine,” Kumar said.

Switchblade 600, AeroVironment’s extended-range, multi-mission loitering munition, continues to gain altitude. In August, the company was awarded a five-year contract for the U.S. Army’s Directed Requirement for Lethal Unmanned Systems. The battalion-level contract, a sequel to an earlier award, may be worth as much as $990 million (Mistral Solutions has filed a bid protest but a stop order has been lifted.).

Kara Kramer, director of business development at AeroVironment, offered a vendor’s-eye view of Replicator. “Most of the time, the DOD does something with one program, and it’s usually owned by one service. Replicator is scanning all the services and touching a multitude of programs. It’s really exciting to see that unification of effort and focus across not just one service but the whole Department of Defense.

“The driving need is for attritable mass at scale to meet a near-peer or peer adversary,” Kramer continued. “We used to think about systems as to how many exquisite capabilities can we layer onto one system, and can we push it out in small quantities, like in the hundreds? The Replicator is pushing industry to think, ‘How can I pare this down to get it to be as cheap as possible and able to be mass-produced?’”

That requires a balancing act. “That tension is to be cheaper but still be compliant with the NDAA [National Defense Authorization Act] we still want. Maybe it doesn’t have everything that the exquisite has. But for a lot of missions, you’re not looking for one UAV to do everything anymore. And you’re not looking for things that need lifecycle support.

“The DOD machine is not meant to turn on a dime,” Kramer added. “But I think they’ve started momentum where they have even the large companies thinking about how to get things to swarm and collaborate in a way that’s really exciting. It’s going to make it sticky in the DoD even after the quote-unquote two-year period is done.”

REMA: ENHANCING EXISTING AUTONOMY

Even though it came from often-experimental DARPA, REMA—Rapidly Experimental Missionized Autonomy (MAS)—takes a different approach.

The purpose of REMA is to provide existing platforms with rapidly changing autonomy so they can execute predetermined missions when operator connectivity is lost, Dr. Lael Rudd, DARPA program manager for REMA, said. “REMA does not focus on the development of new drones. REMA develops the DA2 [Drone Authority Adapter] that connects onto existing drones to provide autonomy using the MAS.”

Rather than phases, REMA’s 18-month program is broken into standalone “Spiral Challenges.”

“Each challenge produces Mission-Specific Autonomy algorithms that allow for stand-alone autonomy capabilities,” said Rudd, who brings experience with MUM-T, PNT and AI from aerospace companies and labs. “The REMA Drone Autonomy Adapter—DA2—maintains these autonomy capabilities that can be leveraged for new spiral challenges. The DA2 also maintains a library of the drone used in each spiral so that the same overall hardware solution can be reused and is backward-compatible as new drones are added. The MAS provides algorithms that allow the drone to be upgraded from remotely piloted operation to autonomous mission execution.”

REMA progressed from announcement to contract awards in just 70 business days—what Rudd calls “the speed of relevance.” Anduril and RTX were assigned contracts for the autonomy adaptor. Leidos, Northrop Grumman and SoarTech were delegated to the mission-specific software. They were to work without firewalls toward common solutions, and Rudd said REMA “has been successfully achieving the planned spiral challenges within the timelines for each deliverable.

“The hard part of REMA is to get a specific solution for a new autonomy challenge while incorporating new platforms into the overall DA2 library,” he added. “These challenges have increasingly aggressive development speeds, starting at 3-month spirals, with an objective metric of reaching 1-month spirals.” These accelerated intervals will hopefully outpace adversarial countermeasures.

OBSTACLES AND OPPORTUNITIES: OBSERVERS WEIGH IN

Participants and defense analysts vary in their embrace of Replicator and various UAS programs.

Military analyst Bill Greenwalt, nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, was one of those who expressed concern before the House Armed Services Committee in October 2023. Among other cautions, he felt the Pentagon’s acquisition system could not meet Replicator’s timeline “except in very limited circumstances.”

Now Greenwalt fleshed out his concerns. “My cautions in that hearing were, ‘Hey, this is a great idea. Maybe we’re going to do a real kickoff on some of these technologies.’ My cautions were that the DOD culture does not do this well and there’s a need for speed and requirements, speed and budget, speed and contracting acquisition.”

Greenwalt broke out those factors around Replicator. “They wanted to do this with kind of existing budget: $500 million is a drop in the bucket, and there’s only so much money to go around. If they’re going to do this, they’re going to have to get money, and a lot more than you have. And that’s just one program.”

Teal/Red Cat’s Matus is enthusiastic about the SRR program. But he too noted hurdles facing accelerated autonomy. “It makes it hard to scale if you’re not sure of how long you’re going to have a contract, to be able to survive and scale their operations, to bring costs down and capabilities up. And there’s just not enough money flowing into drones from the DoD—the vast majority of funding is going toward legacy, traditional systems that I believe don’t represent the future of the modern battlefield.”

AeroVironment business development manager Kramer agreed. “You need to have the orders that justify the investment and pricing model. That’s why there’s so much business development focus on programs of record because we want forecastable orders coming year after year to have a mature manufacturing capability.”

Kramer acknowledged some technical constraints around Replicator’s push for simpler solutions, from navigating over open water to how and when to take humans out of the loop—and even a firm definition of what attritable means to the DOD. She speculated about solutions such as pseudo-satellite navigation and industry integration and interoperability. “It’s in our best interest that our widget works with the government’s preferred battle management system.”

Greenwalt called for “a culture of urgency.” He cited a 2001 DOD goal to have a third of its combat vehicles be unmanned. “They’ve been playing innovation theater for 25 years. In World War II, these programs would have been developed in 18 months.

“I don’t think we have that sense of urgency,” he continued. Instead, traditional technology testing and legacy oversight accounting can raise costs to prohibitive levels. “You have to try to adopt a Silicon Valley way of doing business. You need serial operational prototyping until you get to the point where you’re ready to go into OTA authority production.”

Greenwalt did see a silver lining amid the developmental clouds, including the Army’s “getting through the hoops and doing what’s necessary” to deploy quadcopters. “We’re not the arsenal of democracy; we’re the artisans of democracy, pulling things together. We’ve got to be able to plug and play. The Chinese can manufacture all this stuff; we have to become smarter, to be quick and agile and move new designs quickly.

“We have the tools, but it’s the hubris that we have, that the U.S. military has always been on top.

“That’s why Replicator may actually work, if they start getting them on the field, testing them, seeing what’s going on, maybe letting the Ukrainians use some of them. Replicator can be a test case of doing things fast if they do it right.”