Credit: Virginia Tech

A new soft robot can morph from a ground to an air vehicle by melting the metal within its skeleton, all without gears or motors, a new study finds.

The new drone draws its inspiration from nature — specifically, the way organisms can often change shape to perform different tasks, such as how plants move to capture sunlight throughout the day.

“When we started the project, we wanted a material that could do three things — change shape, hold that shape, and then return to the original configuration, and to do this over many cycles,” study senior author Michael Bartlett at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University said in a statement. “One of the challenges was to create a material that was soft enough to dramatically change shape, yet rigid enough to create adaptable machines that can perform different functions.”

To create a structure that could be either flexible or rigid, the scientists turned to kirigami, the Japanese art of making shapes out of paper by cutting. (This differs from origami, which uses folding.)

The researchers cut kirigami patterns into sheets made from rubbers and composites. These patterns could help the sheets adopt a variety of specific 3-D structures.

The scientists next added a wire skeleton to each sheet that was made of an alloy that melted at a low temperature, which they encased inside a rubber skin. This special metal could stretch into and hold a variety of shapes.

To help this skeleton return to its original shape, soft, tendril-like heaters could melt the metal at 140 degrees Fahrenheit (60 degrees Celsius). After the metal cooled, it could again contribute to holding a new shape.

In experiments, the researchers found this design could morph flat sheets into complex, load-bearing shapes—from cylinders to balls to the bumpy shape of the bottom of a pepper—in less than a tenth of a second. Also, if the material broke, it could heal multiple times by melting and reforming the metal skeleton.

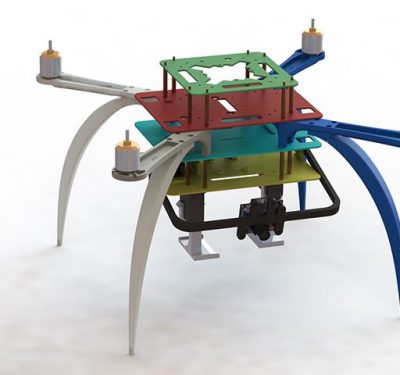

Using this design, the researchers built a soft robot that could transform from a folded ground vehicle to a flat air vehicle, with rotors on the corners of the machine serving as wheels on the ground and propellers in the air. The scientists also used their design to build a tiny submarine, which could change shape to generate a chamber of air to keep it buoyant, as well as a cargo bay to help it collect and retrieve objects by scraping the belly of the sub along the bottom.

“We’re excited about the opportunities this material presents for multifunctional robots,” study co-author Edward Barron at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University said in a statement. “These composites are strong enough to withstand the forces from motors or propulsion systems, yet can readily shape morph, which allows machines to adapt to their environment.”

The scientists detailed their findings online Feb. 9 in the journal Science Robotics.