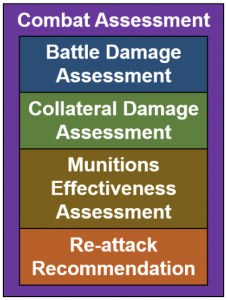

In the military, BDA is the post-strike review conducted after the application of force to determine the effects, including damage done. This concept applies, in theory, to federal policy. On February 1, 2021, the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) launched Advisory Circular (AC) 107-2A, providing “guidance for conducting small unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) operations in the National Airspace System (NAS)” for Part 107.

In the military, BDA is the post-strike review conducted after the application of force to determine the effects, including damage done. This concept applies, in theory, to federal policy. On February 1, 2021, the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) launched Advisory Circular (AC) 107-2A, providing “guidance for conducting small unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) operations in the National Airspace System (NAS)” for Part 107.

Did it hit the mark?

A Cluster Bomb of Rubber Bullets

The policy equivalent of a rubber bullet, the AC “does not have the force and effect of law” and is “not meant to bind the public in any way.” However, because it provides insight into how the FAA interprets its regulations, which do have the force and effect of law, folks should heed it.

At 104 pages, the AC is like a cluster munition containing lots of bullets; too many to fully address at once. This piece provides a high-level assessment of its B-D-A (“before-during-after”) of UAS operations. (Information relating to the operations over people (OOP) rule will be addressed separately.)

Before = Bullseye

The AC hits dead center target for pre-flight.

Maintenance & Inspections: Here’s where to find guidance for equipment maintenance, preflight inspections and other before-ops tasks:

- Remote pilot in charge (RPIC) preflight must-dos—e.g., assess weather (paragraph 5.11)

- List of suggested inspection items (chapter 7)

- Sample preflight inspection/assessment checklist (Appendix E)

- Safety risk assessment, aeronautical decision-making, crew resource management, risk assessment process example (Appendix A)

- Supplemental operational info—e.g., weight and balance, weather & spectrum (Appendix B)

- Small UAS (sUAS) best practices & equipment condition chart (Appendix C).

Pilot Fitness: RPIC physical and mental disqualifying conditions, from to blurred vision to reflex-impacting medications. The RPIC must also be trained and certified to fly (Chapter 6 contains the new training requirements).

Approvals: The AC provides the website to register domestic UAS and applications to register foreign UAS. (For the process to obtain waivers, see paragraph 5.20 and here).

During = Direct Hit

Roles & Responsibilities: The RPIC is responsible for flight safety, supervising any “person manipulating controls,” visual observers (VOs) as well as “automated” UAS. The RPIC has to see and avoid other aircraft, assume control, direct the UAS to safety and have emergency power to deviate from 107 in emergencies. If used, VOs must be able to see the aircraft and communicate effectively with the RPIC.

VLOS: Momentary glances, such as scanning airspace or briefly looking down at controls, do not equate to a loss of visual line of sight (VLOS). There is “no specific time interval” at which loss of VLOS occurs; the key is seeing/avoiding and staying clear of others. First-person view devices are legit but “do not satisfy VLOS.”

Reasonable Conduct: The RPIC cannot operate carelessly or recklessly or fly too fast (less than 100 mph), too high (generally 400 ft AGL; NLT 500 ft below/2,000 feet horizontal from a cloud) or too far (NMT 3 sm from CS).

Part 107 Deliveries. Transportation of property for compensation/hire must be conducted within a confined area within a single state, VLOS and with no hazmat (unless specially approved).

If you plan to fly near an airport or communicate with Air Traffic Control, review paragraph 5.10.

After = Off Target

The AC does not address what pilots refer to as post-briefs. That’s a gap. Instead, it addresses mishaps.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has had a legal requirement for UAS mishap reporting in serious cases. The FAA is catching up by “requiring” RPICs to report accidents within 10 days if there is:

- At least serious injury to any person—a Level 3 or higher on the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) of the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine—or any loss of consciousness; or

- Damage to any property, other than the sUAS, if the cost is greater than $500 to repair or replace the property (whichever is lower).

Reports go to the FAA Regional Operations Center (ROC) electronically, by phone (Figure 4-1, List) or a responsible Flight Standards office and should include:

- sUAS RPIC’s name, contact information & airman certificate number;

- sUAS registration number

- Accident location, date of the accident & local time

- Any serious injury, fatality or property damage

- Incident description.

The mishap reporting requirement, while noble, lands a bit off course. The AIS© is copyright protected and behind a paywall. Applicable standards should be free and transparent; the same for the information collected. It remains unclear whether the public will have access to non-private mishap information. An explanation of why the incident happened, in addition to its description, would also go a long way to alleviate public concerns about UAS safety. Both the NTSB and the U.S. Air Force do a solid job of this.

And One Big Miss

The big missed opportunity is to clarify the remote identification (RID) rule. The AC refers to two others that are not available (AC 89-1, Means of Compliance Process for Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft & AC 89-2, Declaration of Compliance Process for Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft). It speaks otherwise in the future tense about an eventual list of RID-compliant UA* and list of federally recognized ID areas.*

Overall Mission Success

Overall, this policy employment is a mission success: solid guidance about equipment, operations and roles and responsibilities before and during sUAS employment. The new mishap reporting requirement requires a reattack. Finally, while the AC is short on RID implementation, it contains 36 pages of OOP details. So stay tuned for more!

*Links may not be active as this information is not yet available for FAA publication.

Image credit: FAA.

BIO:

Dawn M.K. Zoldi (Colonel, USAF, Retired) is a licensed attorney and a 25-year Air Force veteran. She is an internationally recognized expert on unmanned aircraft system law and policy, a recipient of the Woman to Watch in UAS (Leadership) Award 2019, and the CEO of P3 Tech Consulting LLC.