When it comes to drone applications, there’s no shortage of opportunities in the oil and gas space. Major players like Anadarko, Shell, ExxonMobil and BP are deploying the tech- nology, and smaller companies and service providers are starting to follow suit. But in this heavily-regulated, risk-adverse industry, drone adoption is moving at a slow pace relative to its potential.

Even so, the technology’s safety and fi- nancial benefits are attractive. Vertical asset inspection, leak detection and emergency re- sponse are gaining speed, and industry leaders continue to look forward to beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) flights and automation that can take human operators out of the equation.

It’s clear that drone technology will have a significant impact on the oil and gas industry, which is why the American Petroleum Institute (API) formed an un- manned aircraft system (UAS) policy working group to keep its members cur- rent. Suzanne Lemieux, manager of API’s midstream and industry operations team, said that members’ interest has grown in recent years, and she expects that to continue as remote ID and BVLOS regulations finally take shape, and as there’s more definition on what an unmanned traffic management (UTM) system will look like.

“We see an increase in interest but there is still a very-risk-adverse culture in the oil and gas industry,” she said. “There’s still a lot of hesitancy to adopt these systems until more defined regulations really open the market up.”

While waiting, the oil and gas industry is moving forward on the low-hanging fruit, improving safety and efficiencies in the process.

ASSET INSPECTION

Vertical inspection is one of the most common drone uses in the oil and gas industry today, and flare stack inspection is probably the most promising application, said Philip Finnegan, director of corporate analysis for the Teal Group. With drones performing the inspections, flares may remain in service rather than shutting down; process units can remain operational, saving both time and money while also improving safety.

For Industrial SkyWorks, a company that has worked with big names such as ExxonMobil and Shell, flare stack inspection is its most common service, Marketing Manager Xinbo Zhang said. Just about any asset can be inspected via drone, including boilers, tanks and a variety of offshore platforms. Typical payloads include high-resolution cameras for imagery, thermal sensors for heat measurement and even LiDAR for equipment with more intricate detail.

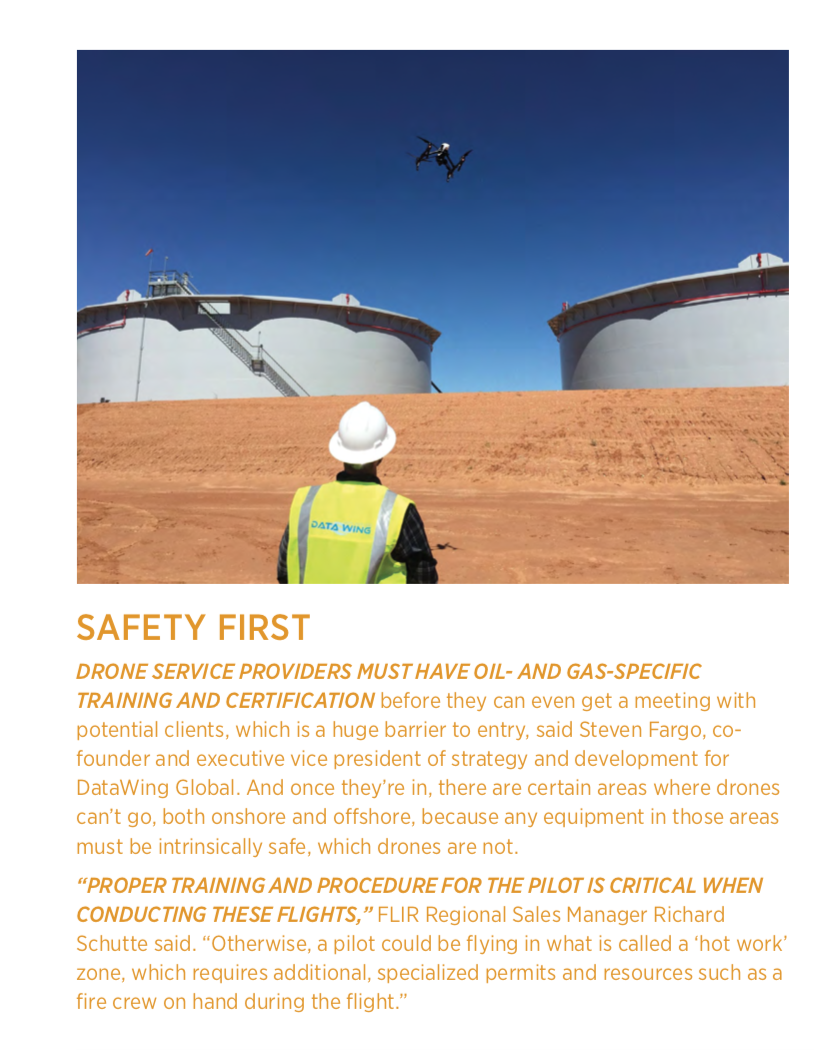

Routine tank farm inspections are one of the most common drone uses. Drones can fly over the tanks to check for integrity issues and corrosion, as well as to detect different gases that might be present, ensuring it’s safe for workers to clean or complete necessary repairs.

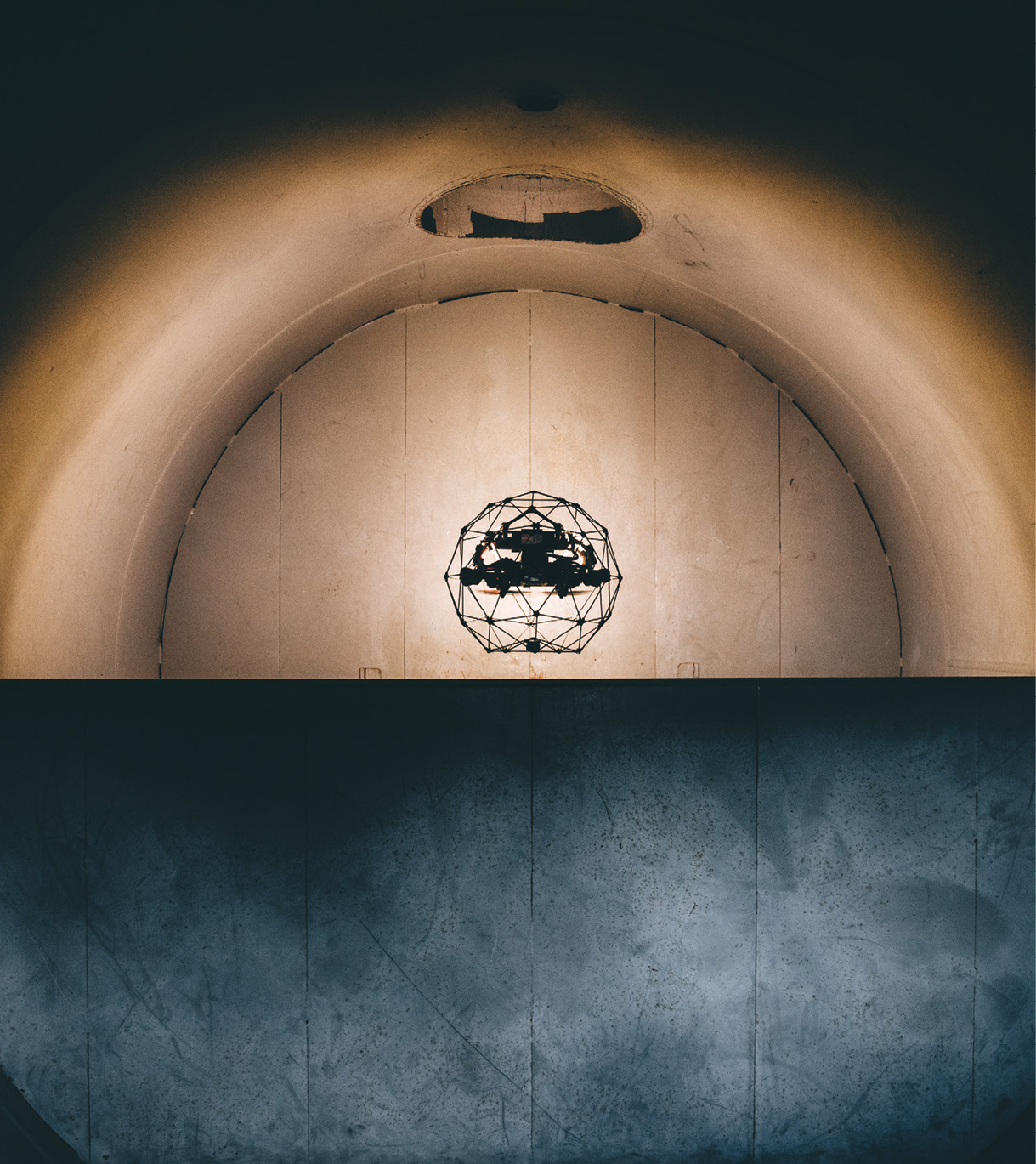

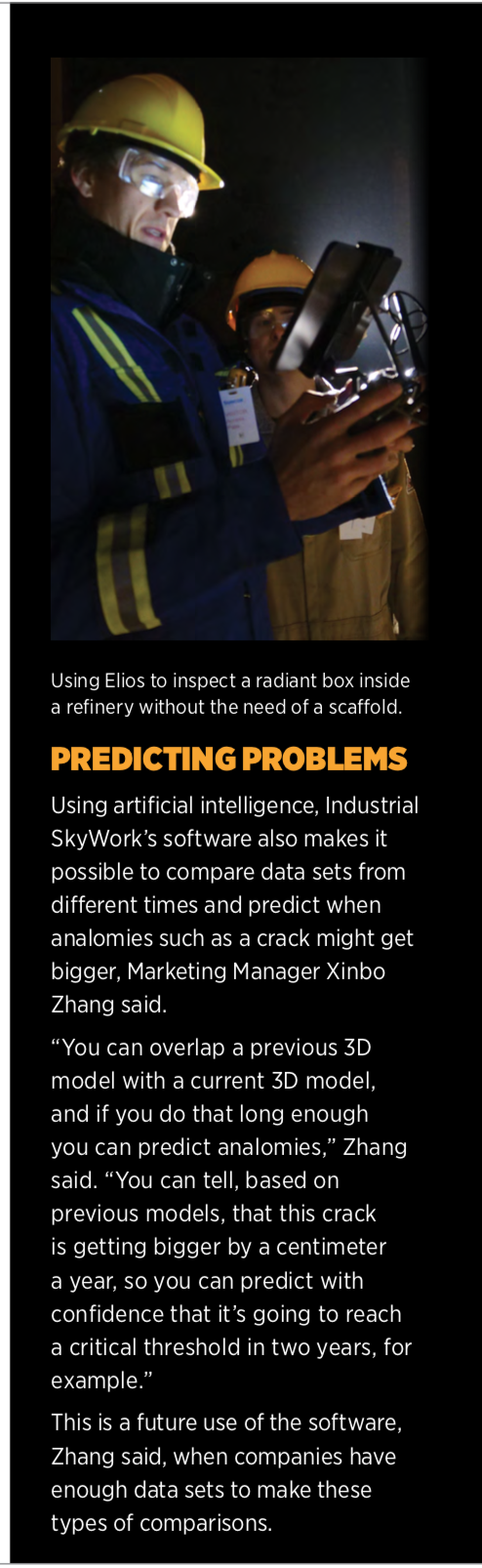

Collision-tolerant drones like the Elios 1 and Elios 2 can perform indoor inspections in confined spaces and GPS-denied environments, such as tanks, that may be difficult or dangerous to get to, said Junio Valerio Palomba, area manager with Switzerland-based Flyability. The latest version represents a complex re-engineering of the drone, which features sensors that make it easier to maneuver and a 10,000-lumen light in the central payload that helps users identify certain defects, such as corrosion and pitting.

TRAC Oil and Gas, a UK-based company that provides maintenance and inspection services, started using the Elios 1 late last year and took delivery of the Elios 2 earlier this year. They first started looking for a drone to perform inspections in 2017, but the challenge was finding a system that could handle magnetic interference and fly in manual mode in a GPS-denied environment, Business Delivery Manager Jan Stander said.

TRAC plans to use the Elios 2 to perform class inspections of the structural integrity of cargo tanks, which is something that needs to be completed every five years, Project Manager Lauren Stammers said. Typically, rope teams are sent in to perform these inspections, which is both time-consuming and dangerous. The Elios can identify cracking, buckling and corrosion in less time without putting workers in harm’s way.

The team also has used the system to scan for dropped objects before putting a tank into production, Stander said. The Elios can do a verification sweep to identify anything left behind, such as debris or tools, that could be sucked up into the pump and cause damage.

The Elios isn’t replacing the rope access teams, Stander said, and is seen more as a supporting tool than a primary tool. “The UAV can’t do everything that a person can do,” Stander said. “With these class surveys, there are not just requirements for visual inspections. There’s also an ultrasonic testing requirement. There are no UAVs available that can do that, so there’s still a need for people to go up there.”

LEAK DETECTION

Leak detection is becoming one of the more common drone uses in the oil and gas industry. There are a number of federal- and state-level hydrocarbon emission rules the industry must follow, creating a need to monitor how much of certain gases, especially methane, go into the environment, said Steven Fargo, co-founder and executive vice president of strategy and development for San Antonio-based DataWing Global.

The industry has used optical gas imaging (OPI) cameras to do this for years, but now can fly these cameras on a drone, enabling them to identify and quickly fix leaks.

DataWing Global is among the companies that offer this solution, and it has partnered with FLIR Systems to make it happen. The FLIR OGI camera and the DataWing Global software, Tally, can be integrated onto a drone, allowing inspectors to cover more ground and to identify leaks faster than with traditional hand-held cameras.

FLIR’s OGI cameras use spectral wavelength filtering to visualize the infrared absorption of gases such as methane and benzene, FLIR Regional Sales Manager Richard Schutte said. The camera can see hydrocarbon gas plumes that are invisible to the naked eye. It can find more than 200 hydrocarbons and is commonly used to identify fugitive emissions of methane during leak surveys, structural inspections and thermal audits.

“Reducing fugitive emissions has been a crucial goal in the oil and gas industry for some time, as it not only benefits the environment but it also helps these companies save money by keeping product in the line,” Schutte said. “When used in a refinery, the drone can remotely inspect areas that would normally require extensive man-hours and equipment like a self-contained breathing apparatus [SCBA] or man-lift.”

Viper Drones also has partnered with FLIR to offer aerial OGI camera inspections, said Leon Shivamber, chairman of My Drone Services and Viper Drones, and can do so via a live video feed. One person can control both the camera and the Viper Vantage drone at the same time, eliminating the need for two people to be part of the inspection. The robust drone has a long endurance time and isn’t impacted by interference from the energy production field.

During a demonstration for a potential oil and gas client, the drone identified a leak on top of a tank the team had no idea was there, Shivamber said.

“Their practice was to inspect that part of the tank once a year because it’s so difficult to get to,” he said. “We showed them how they could inspect that section every month, every week, every day if they wanted. We find, on average, if you inspect once a year, you’re going to miss a leak by six months. But if you inspect once a month, you only miss a leak by two weeks, on average. If the leak is big enough that’s a huge benefit.”

The Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) is working on a methane leak detection system as part of a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) project. Now in its third phase, the Smart Leak Detection System/Methane (SLED/M) technology will automate inspections of oil and gas facilities. Part of that project involved putting OGI cameras on fence lines to monitor pipeline pumping stations and then automatically alerting the operations center when there’s a leak. Now, drones are being used to fly the cameras.

SLED/M expands on the limits of Midwave Infrared (MWIR) sensors with machine learning-based detection algorithms, enabling them to reliably identify methane leaks. The system acquires and processes data to autonomously decide whether a substance is hazardous.

Images are hand-labeled as having methane or not having methane, and identification is possible without flagging everything moving in the image, such as wind-affected vegetation, dust and humans, Engineer Heath Spidle said. This reduces the number of false alarms that come from human error, and the resulting wasted time and complacency.

“Operators can see where methane is leaking and then backtrack to where the leak is coming from. They can see plumes in the video imagery, enabling them to stop and prevent larger leaks, and it does all this in real time,” Spidle said. “A lot of sites are in remote locations and may not have 5G cell coverage or WiFi for streaming, so this has onboard processing and does deep learning at the edge so you only need a single binary signal that says, ‘Hey, there’s an alarm here you need to go check it out.’”

PIPELINE EVALUATION

While BVLOS flights will make this more feasible, there are pipeline inspections that can be done today beyond leak detection, including identifying structural problems and right-of-way encroachment, said Harjeet Johal, vice president of energy infrastructure at Measure. “We can capture video of a stretch of pipeline and from the video extract geospatial differences between pixels. Those pixels translate to the distance of anything encroaching the right of way, which could be vegetation or a new building.” Through Measure’s cloud-based software, Ground Control, collected data can be uploaded directly from the field to the cloud server for access by a full team.

AeroVironment flies drones to monitor pipelines as well, evaluating trees or other vegetation intruding onto the easement and identifying shifts, said Mark DuFau, director of business development with the company’s commercial information solutions. The team worked with BP in Alaska a few years ago to monitor pipeline shifts caused by temperature changes, as well as other conditions not visible from a drive-by inspection, such as structural changes.

DataWing Global uses infrared sensors to monitor vegetation that might be dying from a slow leak, Fargo said. The team is working on a project now that involves flying over buried pipelines once a month. If models show vegetation is starting to die, it could indicate that repairs are needed.

EMERGENCY RESPONSE

Emergencies are another area drones can be put to use within the oil and gas industry. For example, Shell Deer Park flew drones after Hurricane Harvey to inspect tank roofs that might have been compromised from the heavy rains. They were able to complete these critical inspections in a matter of hours, rather than the days or weeks it could have taken if the inspections were done by man.

Drones make it possible to access restricted or hard-to-reach areas so decision makers can quickly see what’s needed to get back on line, and then allocate the appropriate resources to make it happen.

AeroVironment’s systems have helped during oil spills, DuFau said. They can fly a beach both before and after a spill, and then look for changes using multispectral cameras. Having this information at hand makes it easier for SCAT teams to start the cleaning process.

Cape Aerial Telepresence software from Cape offers real-time results through what CEO Chris Rittler describes as a telepresence and data management platform that is similar to Zoom or Web Ex. It can be used during critical incidents such as a fire, leak or spill. The software provides a live drone feed to a standard web browser, meaning decision makers can monitor a flight remotely from anywhere in the world, a capability companies like Anadarko have successfully used. Through teleoperation, drones also can be controlled from that same feed.

“Getting visibility to as many experts as possible is a high priority,” Rittler said. “If there’s a fire the first team on the scene can put a drone in the air and everyone else can participate by viewing the live stream of what’s going on.”

CONSTRUCTION

Oil prices have stabilized, DataWing Global’s Fargo noted, and that has led to bigger operating budgets and capital spending in the industry. A lot of investment dollars have gone into building pipelines to increase drilling operations, as well as into facility construction. As with traditional civil construction projects, drones can be used for pre-planning and to monitor a project’s progress. They also can help with land-owner negotiations.

Measure flies drones for oil and gas construction projects, Johal said, capturing parameters such as the depth and width of trenches for pipelines that are being constructed. The raw data collected is turned into a 3D model that helps ensure lines are laid properly. Drones also can be used for surveillance.

THE FUTURE

THE FUTURE

As regulations become more defined and the cost savings become clear, drone use will increase in the oil and gas industry. In the next five to 10 years, Fargo sees autonomous drone-in-the-box solutions being deployed in the field. Multiple drones will be monitored by one person from a control room to perform BVLOS applications such as pipeline inspections. Drones will just be part of the tool kit, much like SCAT systems or other technologies that are standard today, Rittler said. With Cape, the technology already exists for drones to be remotely launched and controlled; it’s just a matter of waiting for the regulations to catch up.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning will contribute to more advanced software, which will also become more integrated, offer more real-time capabilities and provide better organized data. Drones will complete volumetric analysis and digital terrain modeling, and may even be able to deliver supplies to teams in remote locations someday.

“The oil and energy industry is a more cautious adopter of technology. We expect that many of the technology benefits from drones will eventually make their way into this industry but at a deliberate pace,” Shivamber of Viper Drones said. “We have hardly begun the process of applying the drone as a tool for enhancing industry, but these are meaningful solutions that bring a lot of value and will be adopted as the technology and capabilities of service providers improve.”