Black & Veatch UAV pilots flew the massive Gross Reservoir Dam Expansion Project in Colorado as part of the company’s project management role.

Based in Overland Park, Kansas, 106-year-old Black & Veatch is one of the largest employee-owned companies in the United States, with 2019 revenue of $3.7 billion. Its engineering and consulting services range across the full construction cycle, and the company has used UAS from massive, complex U.S. infrastructure inspection to powerplant construction in the developing world. The result has been better quality, efficiency, safety and profitably for clients and employees alike.

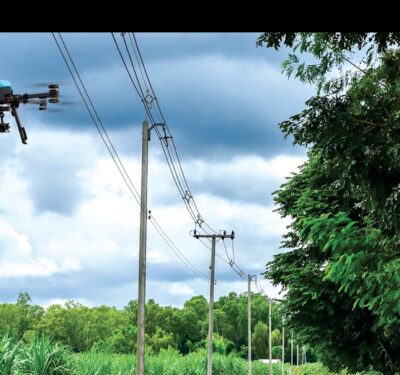

Among its notable accomplishments, Black & Veatch provided the telecom engineering design, tower analysis and network equipment procurement services for a record-setting 60-mile BVLOS powerline inspection experiment with Ameren using a Pulse Aerospace Vapor-55, Latitude Engineering HQ-90 and a Near Earth Autonomy LiDAR sensor. The company is developing artificial intelligence and machine learning to augment human analysis.

Leading the company’s charge for drone services is eight-year Black & Veatch veteran Jamare Bates. Currently, Bates wears two hats—or helmets—as director of unmanned aircraft systems operations and, more recently, project manager and “technology catalyst” for the company’s federal services business, out of Arlington, Virginia. A structural and civil engineer by education, Bates came to drones during the company’s Leadership Development Program. It was 2015, and at the time Black & Veatch had one drone and two pilots. Back then, Bates pitched what he saw as a huge opportunity to the company’s IgniteX Growth Accelerator program, a corporate incubator that supports promising technology and techniques from inside and outside the company. Now, Black and Veatch flies some 30 pilots and 30 drones.

Recalling the Accelerator experience, Bates said: “It’s like a “Shark Tank” mentality; you sink or swim on your own. You pitch ideas, compete for funding and then you run your idea like a startup company. So, I moved out of my federal services role for a couple years and tried to stand up some drone operations. Those operations have since graduated and permeated throughout the company.”

Bates recently sat down virtually with Inside Unmanned Systems to discuss how UAS have and will influence Black & Veatch’s practices. Edited excerpts from two sessions follow.

Up in the Air

We have on the order of 20 to 30 pilots right now. As a company, that’s not a big footprint so we augment with drone service providers. When you’re flying in areas you’re not as familiar with, having a local presence can be important.

BV owns [DJI] Phantom and Mavic drones that are typically flown for commercial line of sight flights. They meet the needs of the market [but] we have customers that have a reluctance to use a Chinese-based product for data security concerns. I think you’re going to see some of your more sensitive infrastructure move into American-made drones. When companies start to understand their technological know-how of the air platform and the sensors, coupled with the engineering understanding of what you need to actually find, see and scan, those vendors are going to flourish.

Infrared is sometimes used during flights for solar projects, where an image may show a solar panel looks fine, but an infrared may show the panel is broken or inoperable. Things like BVLOS or highly complex LiDAR flights require customization. You’re selecting the components, the batteries, sometimes the frame, flight controller, camera, onboard computer, etc.

Capturing and Processing

Traditional infrastructure inspection relied on hand-documenting the image location. This was time-consuming and difficult to maintain accuracy. BV uses the drone to augment image capture for asset management. Most of the data that is collected is imagery, sometimes video. LiDAR is the sensor that is used second-most.

The benefit of drone-based image capture is that the drone’s positioning computer knows where the drone is in three-dimensional space when the image is captured. There is some level of accuracy in the horizontal location, as well as the elevation or vertical location. GIS professionals can integrate drone imagery into a system that automates the location of the image digitally. This reduces the error and provides faster processing.

We have a lot of professionals with GIS experience, and so, when it comes to processing tools such as ESRI and ArcGIS, a lot of that work is done by our in-house GIS teams. There is other third-party software—Pix4D and [Bentley Systems’] ContextCapture pop up a lot—and you’ve got third party vendors. It’s cloud-based, so there’s no need for Black & Veatch to process those types of services for making 3D models or renderings.

We don’t currently have internal LiDAR [processing] capabilities. What’s going to cause a big shift in LiDAR is when BVLOS becomes the norm. The value really increases exponentially when you scan multi, multi miles and miles of distance. Imagine LiDAR scans that go 20, 30, 40 miles at nighttime and then in the morning you’ve got all that data to analyze. That’s when things start to become pretty valuable from a market perspective.

Black and Veatch uses drones to inspect hard-to-reach utility assets by collecting critical thermal imaging, hyperspectral imagery, HD photo, 4K-resolution video and LiDAR point cloud data.

Camera Requirements

The next important feature after highly accurate positioning is the camera. The important aspects are pixels, shutter speed and focus capabilities—typically, 20-plus megapixels at a minimum, 1080P video. Some cameras have lower megapixels but may have an ability to zoom 30x. Some

cameras are the opposite, relatively fixed in terms of zoom but have a higher amount of pixels at the starting point.

In some powerline situations, staying 10-15 feet away from the asset helps with electromagnetic interference, which can affect the flight controls and magnetic compass within the UAS. In that situation, you want a camera with better zoom capabilities so you can fly further away from the asset and still get good imagery. Shutter speed is important if you are doing photogrammetry. The speed of the shutter has to be timed with the speed of flight or you can get drift between the images.

Safety First

We saw a statistic that for individuals who either fly helicopters or climb transmission line towers on transmission line inspections, there’s 10 to 20 fatalities a year in the industry. Some vendors are trying to take video and use machine learning to spot unsafe activities, flag those activities and notify someone.

For example, you’re a safety inspector on one side of a site and you can’t see what’s happening on another side, but you have constant monitoring from a drone. If you have everybody on site wear a particular safety gear that the drone can see, the drone can give notification if someone walks into a zone they shouldn’t be in that you identified with a GPS coordinate. Or they’re capturing topography and there’s a dip of greater than so many feet but there’s pieces that are not there for safety tie off. We are seeing companies develop safety monitoring algorithms to do that on a more regular basis.

Better Asset Maintenance

A customer had hundreds of miles of transmission line that needed to be inspected

and thousands of miles of distribution line, and they were just doing ground-based and climbing. They were breaking their assets into sections they could do once a year, so in five years they get all the sections inspected. That means if things happen within that five-year span, you’re not actually catching it. Now you’re fixing four years of problems when you don’t have money for it.

With a drone you’re going to see all the assets every year. So now I’m able to spot things quicker and maintain assets, rather than they break and I have to repair them. That’s the crux of the paradigm shift the industry is moving into.

Last year, a company in our accelerator incubator had an autonomous landing platform for drone-based bridge inspections. It takes off from a docking station, flies around the bridge and then comes back and lands. But you could also imagine it being stationed at the bridge and someone from an operation center 10 miles away can say, ‘Hey, we had a really bad ice storm the other day, go fly a cycle through the bridge and give me a report back’ and the drone just goes. Also, a lot of internal inspections could benefit from confined-space flights—now, people hanging from ropes do that.

Could we monitor a site in Africa from Arlington? Absolutely. There are companies that have some really high-powered remote monitoring capabilities. We have a global security team that has done research on sites in remote parts of the world where there are security concerns like extremist groups. Those places need power and infrastructure the most, but sometimes they have the most constrained budgets to get there. These tools can really help augment what you can do.

Better Machine Learning

You have these massive, localized sites—a multi-hundred million-dollar power plant of some kind. What a drone gives you is unbiased monitoring. You can also imagine programming the drone to fly a perimeter that you would have to drive in a vehicle.

Nowadays, you have a human element—someone who walks the site taking pictures with a camera. I only see where he or she is turning the camera. If you’re flying the drone half a mile away, well that’s really a mile radius the drone can see if it’s up high enough. If I fly a site at a certain height in a lawnmower pattern back and forth every day or every week, I’m capturing the exact same thing every single day. You don’t have to say, “The guy was walking the site yesterday, and it was getting dark, and he was tired. Maybe he missed it.” The drone doesn’t miss anything.

What you’re feeding into the computer in terms of data processing is change detection—over time it learns what to find and starts to spot changes. Capturing that video record and turning it into machine learning data for increasing your ability to manage the project is where the leverage really comes in.

Better Project Management

There’s a handful of vendors that do “progressing.” They scan a site on a regular basis, build a model of the site and compare it to the design model of the project. Then they’ll compare the model’s progress to the schedule progress and provide analytics.

We have a great story for this. We were working on a 100-acre-or-something site, and there was a large piece of equipment delivered that didn’t get logged properly and was effectively lost. It was a big piece of equipment—more expensive than an expensive sports car. “It was delivered.” “No, it wasn’t.” There are claims and everyone’s ire is up. We were able to go back through the video feed and spot some things that had been moved around the site differently than what was expected. They found the equipment and saved multi-tens of thousands of dollars in claims and litigation.

Better Processes

[For construction] I think you’re going to see stuff on the ground first. It’s just the proportion of activities that happen on the ground versus what happens at height. A company in our accelerator program called Built Robotics has unmanned excavators. If you’ve got to clear dirt on a two-acre site, and then put in one pole and string the wire to that one pole, you only need the drone for that one wire string. But you’ve had a bulldozer out there pushing dirt for three or four days.

We’ve also worked with companies that do unmanned rovers and unmanned submersibles. We have some pipe inspection robotics that are tethered rovers with pretty powerful AI that can drive through pipes. I think what will happen is more vehicle-based drone deployment—you’re driving and you need visibility on something you can’t quite see.

Replacing People?

No. It’s about utilizing people better so they can do more work and extend their career. We’ve got people that do rock climbing. They climb up 300-foot-tall wind turbines. They climb up 100-plus-foot-tall telecommunications towers. We still have people who hang off the edges of dams and inspect the whole face.

That rigger can do one dam in a month. But I can put that person in a command center and have drone pilots fly 10 dams in two weeks and feed that data back to the expert who now has a team inspecting those dams. Their knowledge is the most important part of the process—the drone just gets the data.

A Better Tomorrow

I can envision a time when drones and ground-based autonomous vehicles are used to move material and people around large job sites. I think we are 5-10 years away from that. But soon you will start to see that integrated more into repetitive activities, like earthmoving and moving materials.

The biggest future opportunity for the entire industry is BVLOS. The ability to do BVLOS flights will lead to entirely automated assessment systems for infrastructure management. Large-scale, semi-real-time infrastructure monitoring will change the way we plan and decide on future construction projects. It gets us out of break-and-fix mode and into risk-based decision-making from measurable data.