Capitalizing on a high-tech location and forward-thinking leadership, the Menlo Park Fire Protection District has become a leader in UAS response. HERE’S HOW.

Perhaps Chris Dennebaum’s family was on another line. But actually, Captain Dennebaum, UAS program coordinator for the Menlo Park Fire Protection District, had a job-related reason to stop describing his department’s multifaceted drone use. There’d been a car accident. Engines were rolling. Time to go.

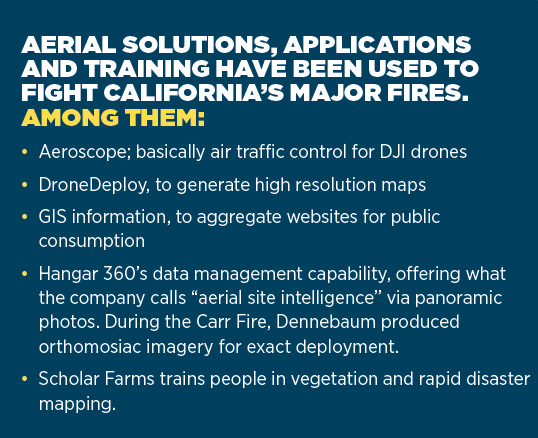

Dennebaum was well worth a call-back because his UAS team has gained notice in a state where potential disaster is never far from a Californian’s mind. When easterners ask about missing the seasons, the gallows-humor reply is, “We have four seasons too: flood, mud, fire and earthquake.” Ignited by a fire under power lines, 2018’s Camp Fire, the deadliest in the U.S. in a century, turned the town of Paradise into a fiery hell, killing 85 civilians. Four months earlier, sparks from a flat tire had set off the Carr Fire, which burned nearly 230,000 acres, killed three firefighters and five civilians, and forced 38,000 people to evacuate from the city of Redding. The year before, a malfunction in a private electrical system led to much of Santa Rosa being destroyed by the massive Tubbs Fire. All were exacerbated by California’s “fifth season”—drought.

Closer to my home, the December 2017 Thomas Fire and subsequent mud-debris flow killed 23 and transformed the affluent town of Montecito from an upscale refuge into a frantic refugee zone. In the 11 years since my wife and I moved to neighboring Santa Barbara, we’ve evacuated four times: twice voluntarily, twice under mandatory alert. Just recently, watching tennis on TV was punctuated by earthquake tremblors. Trouble in paradise, indeed.

My hometown Santa Barbara City Fire Department is updating its drone plan, so discussing it was premature (too bad: the lead drone operator’s name is Sky). As usual, Menlo Park was at the ready.

Flying a one-foot gap between the floodwaters of San Francisquito Creek and the base of Highway 101.

FIRST RESPONSE MEETS UAS

The Menlo Park department encompasses seven stations, 10 apparatus, 100 firefighters—appropriate for what Dennebaum called a “small-medium-sized city.” It also flies 32 UAS, from DJI Sparks and Pros up to Enterprise Duals, Matrice 210s and one Matrice 600. Ten pilots deploy across all three shifts, with 15 more in training. “That’s a pretty robust UAS program,” he allowed.

Dennebaum joined the department in 2006 as a probationary firefighter. Five or six years ago, he bought a Phantom 3 “to take pictures of my family.” As often happens when public safety organizations begin to discover UAS utility, colleagues who knew he had a drone asked him to explore its first-response potential.

Adoption accelerated. DJI donated a drone, which sparked community meetings about how UAVs could aid the department. “How would our public feel about it?” gave way to “lots of support, not a lot of negativity,” Dennebaum recalled. “It’s Silicon Valley.”

“Firefighting tactics haven’t changed in hundreds of years. Adding this technology is new, and we’re moving from the radio to the screen.”- Fire Captain Chris Dennebaum, UAS program coordinator, Menlo Park Fire Protection District

Dennebaum applied for and received a blanket COA—Certificate of Waiver or Authorization— which the FAA grants for flying small UAS under 400 feet except for restricted areas such as airports and large cities. Menlo Park now has a second, jurisdictional, COA, which recognizes the skills to fly a broader airspace, such as that near the Palo Alto airport.

An Intel Falcon 8+ surveying destruction at the Camp Fire.

In July 2016, the chief issued a report to the fire district called “Rise of the Machines.” “That was the chief’s vision,” Dennebaum said, referring to Fire District Chief Harold Schapelhouman, who in 2017 would be recognized as “among the nation’s leaders and experts in urban search and rescue” by The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA). The plan outlined how UAS-derived information could be disseminated. “That’s the biggest challenge of all this,” Dennebaum said. “Firefighting tactics haven’t changed in hundreds of years. Adding this technology is new, and we’re moving from the radio to the screen. We continue to struggle with making information actionable.”

A key decision was made to train firefighters to be pilots rather than the reverse. “It comes down to information processing. Firefighters flying drones understand what key information commanders and crews need in real time, and in what order they need it. We’d have to explain what’s important to an outside photographer.” That approach, Dennebaum told AOPA, was “carefully considered and not particularly easy. It takes a man off the line.” Still, the department thought the knowledge gain was worth the personnel pain.

Technology companies from and beyond the area abetted Menlo Park’s UAS growth. NASA UTM personnel assisted with that first COA application. DJI offered joint trainings at the Stanford Linear Accelerator’s facilities—“We continue to give them input into the development of better tools for public safety.” To share best practices, Menlo Park Fire hosted a drone symposium at Stanford in June 2017. It drew about 100 fire service figures, including state and national personnel, industry players and NASA staff. “We tried to keep it from being commercial,” Dennebaum, by then a fire captain, recalled. “On a grander scale, it was about, ‘How can this affect public safety?’

“There’s a core value to sharing information and collaboration, to learning from others and making connections,” Dennebaum continued. “There were different pieces of technology, demonstrations. It was very successful.”

I’VE SEEN FIRE, I’VE SEEN RAIN

MPFD’s UAS have been deployed across an array of first-responder situations. Most memorable for Dennebaum was working 2018’s Carr Fire.

“We found areas of complete and total devastation. I’ve never seen where a home was blown off its foundation by a fire itself—a fire tornado. There was no topsoil in some areas. The fire was moving at over 100 mph.”

MPFD traveled nearly 250 miles to lend its expertise, with Dennebaum flying a Phantom 4 over four days. Working with several sheriff’s departments and DJI, the UAS team covered a quarter mile every 15 minutes and a mile radius every hour, capturing high-resolution images at 200 feet. Quick posting allowed residents to check on their homes, insurance companies to expedite claims and FEMA to make damage assessments. There also was in-house added value, Dennebaum noted. “Our chief is proactive. He believes in the benefits of the technology, and not only that we can provide value, but we also get pilot experience and push the technology forward. He offered our services without any guarantee of reimbursement.”

Over two days at the Tubbs fire, two MPFD UAS teams documented damaged areas and generated orthomosaic imagery that guided UAV deployment. Burn patterns and historic features were documented for Cal Fire investigators and law enforcement. Thermal imagery vetted sites before search dogs were sent into structures.

But if firefighting offers the most dramatic UAS use, the department “treats the drone as an all-risk tool, applied to things beyond fire and rescue,” Dennebaum said. Construction, roof and solar inspections head off problems before they flare; investigations find out why fires happened. Last year, Dennebaum flew a Mavic Pro to evaluate the remains of a redwood tree after a chunk fell onto a roof previously damaged by lightning.

Surveying devastation at the 2017 Tubbs fire.

The flooding of San Francisquito Creek in early 2017 especially demonstrated UAS versatility. “The creek runs under Highway 101,” Dennebaum explained, “and all the debris was backing up into trash racks underneath the bridge. Caltrans needed to access the trash racks, so we flew a Mavic Pro between the rising flood water and the bottom of the bridge. There was less than a foot of clearance.”

In keeping with his collaborative nature, Dennebaum cited a best, if grisly, UAS use by the Fremont Fire Department—“our neighbor across the bay. There was a chemical suicide. They were able to fly the drone inside the tent and read the suicide note, and know the chemicals before the hazmat team came in.”

FLYING TO THE FUTURE

Dennebaum portrayed a department charting its path toward a UAS future.

“Now we have a new fleet [eight in all] of Mavic 2 Enterprise Duals. “We can support more pilots with less equipment. Thermal capability. Thirty minutes in the air. Handling sustained winds of 15-20 miles per hour” are just some of the attributes he cited.

“We have MSTAR—Mobile Special Technology and Resources—a dedicated drone response vehicle. It’s an upfitted Mercedes Benz Sprinter van with a satellite dish on top, a 48-foot mast, camera, lights, two work stations. It holds a number of drones and streams feeds.” The MSTAR is “testing additional streaming equipment so we can have more robust communication.”

Still, “there’s no one tool that’s perfect for every application. We need to add a fixed-wing component to map large areas. Everything we have is rotor—hovering, covering smaller areas.” He’d also like to have a drone in a box to protect a nearby powerplant and target resource needs for wrecks on the hard-to-traverse Dumbarton Bridge—and a system that would eventually cover the entire district.

(TOP) A Menlo Park DJI Mavic Pro at the ready. (BELOW) Drone-dispatching at the Carr fire. (L to R) Chris Dennebaum; then-intern Jack McCandless; innovation technologist Mike Ralston.

As Dennebaum recognizes, technology serves humanity. “We’ll continue to push the tech forward, so our people are as prepared and outfitted as possible when they go out.” Focused training is taking place around the Mavic Duals, and the department just added DroneSense, a public-safety-dedicated system for collaborative flying and data recording/display. “You can fly every drone in our fleet through it, and stream through it, and I can do fleet management.”

Personnel from Menlo Park also are on the state’s UAS policy front line. They’re active with California’s Firescope initiative, which shares professional and governmental expertise. As members of the subcommittee on UAS, they’re exploring ROSS (Resource Ordering and Status System), a national interface to automate and quickly mobilize inter-agency response to wildland fires.

Dennebaum plans to continues meshing technology with people skills. “There’s still the issue of who flies when we’re all firefighting. We don’t have fulltime staff right now, and it will probably be cross-staffed in the future. There’s still room for firefighters operating drones in areas like search and rescue, but a lot of what we do can be covered autonomously.

“Why send a person when you can send a machine?”—that pretty much sums up Dennebaum’s UAS philosophy. “A firefighter at the end of a 100-foot ladder to see if the water is going to the correct place—a drone can do that, get pictures in real time.

“The ability to track our firefighters inside and outside of buildings is the gold standard of firefighting safety,” he concluded. “It’s a risk-reward computation. Will we risk a $1,000 drone? We’ll risk a $25,000 drone—a DJI Matrice 210 with a thermal and a 180-times zoom—against a life.”

“There’s a core value to sharing information and collaboration, to learning from others and making connections.”