Unmanned aircraft can be better, faster and cheaper than conventional security.

The looting of construction sites may be a billion-dollar problem in the United States. Now, drones may help construction firms protect their sites from thieves.

A GROWING PROBLEM

The direct losses from construction theft may cost anywhere from $300 million to $1 billion annually, according to a 2015 National Equipment Registry study based on data from the National Insurance Crime Bureau and National Crime Information Center. Additionally, the recovery of stolen items may be as low as 7%, according to a 2019 study from Joseph Shrestha and Dustin Osborne at East Tennessee State University at Johnson City.

Construction site thieves not only steal materials, but tools and equipment as well. On average, trucks are the most expensive targets, with an average loss of roughly $42,000 per incident, the 2019 report found. Furthermore, “certain tools are customized for certain jobs—you can’t just buy them at Home Depot,” said Jack Wu, co-founder and CEO of the world’s first robotic aerial security company, Nightingale Security in Newark, California. “So replacing them can take weeks.”

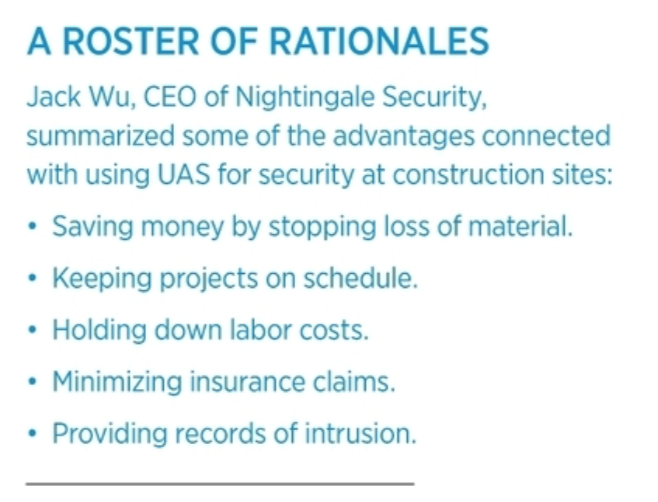

Wu itemized a roster of rationales for using UAS to enhance site security.

Construction sites make attractive targets, he began. When they are not active, they are often left unattended, with only a fence to protect them. Securing them against thieves can be difficult, as they are often large, “which makes them easier to hit and harder for security guards to cover,” Wu said. “Due to the unprepared nature of construction sites, they typically also don’t have a lot of security cameras either.”

Even if a site does have cameras, “thieves can cut power to them easily,” Wu said. “Sometimes thieves just spray-paint ground-based cameras, or use a pellet gun to take them out.” And construction site cameras often do not see well or at all in the dark, “as construction sites usually don’t install thermal cameras due to their expense.”

Much remains uncertain as to how much is actually lost to construction theft annually. “No one wants to talk about it—they want to keep it hush-hush,” Wu said. “No one wants their insurance rates to go up. A lot of times, construction companies that get hit just eat the costs. They would rather pay just one time instead of paying consistently higher insurance for the projects they do, and they don’t want the bankers financing the project to be concerned either.

“You don’t want to advertise that stuff is being stolen from your lots—it makes you seem incompetent. It’s all kept low-key.”

Still, construction theft appears to be a growing problem, in part because of the low risk of getting caught and the potentially high rewards, the 2019 study reported. “Lumber prices are going up, which makes stealing building materials even more attractive,” Wu said. “And COVID has created a lot of financial hardship as well. Construction theft was already on the rise, but unemployment has created a new class of criminal who are not bad people, just people in need.

“There’s a lot of money being lost,” Wu added. “With the rise in material costs, construction companies can’t keep the problem quiet for long. Before, when they lost lumber, it was cheap to replace, but now that lumber prices have gone up four times, they will have to file for insurance.”

Construction theft does not simply lead to costs in terms of lost materials and tools. “It hikes up insurance costs,” Wu said, “and it leads to project delays—when you don’t have tools or materials, you can’t do much. So you have people on salary getting paid while you wait to get back what you need, and you have interest accumulating on the loan to build the project. A lot of times, the biggest costs from construction theft isn’t the lost materials or tools; it’s the work stoppage.”

DRONES TO THE RESCUE

Again, drones can combat such theft. “There is a lot of incentive to using drones,” Wu said. “They have the ability to monitor vast areas very easily, doing it cheaper, better and faster than traditional options. They can see better, using thermal cameras, and so can operate anytime, anywhere, day or night, rain or shine.”

Compared with standard security guards, drones are more economical, Wu said. “Expecting one or two guards to cover that large an area has limitations, too, and for them you would need a vehicle and a guard shack for patrols. If it’s cold, you would need to provide them heat, and if it’s hot, you would need to provide air conditioning, and the larger the guard force, the more infrastructure you would have to build and then tear down afterward.”

Systems like Nightingale’s can set up automated detection zones for the drones. “If they detect a person or vehicle, they can automatically alert a guard,” Wu said. “The guard doesn’t have to always pay attention to it.”

Drones can also record everything they see. “Security guards may call the police, but the problem is that if they are just seeing it with their own eyes, there’s no record, just what they say,” Wu said. “Insurance guys want to see auditable material, so having video from a drone is of benefit there.”

In addition, compared with regular security cameras, drones have no power cables a thief can sever. “They also fly at 150 to 200 feet, and so won’t get hit,” Wu said.

SECURING A SITE

Nightingale’s Blackbird drone-in-a-box system uses visible and thermal sensors to provide scheduled autonomous patrols and automatic threat response. Its RAID (Robotic AI Intrusion Detection) system sends intruder alerts to a security team, and the system has a manual detection option during emergencies. Base stations can be installed on rooftops or elsewhere on a site, and the system can be integrated with existing sensor setups.

To secure a construction site, Nightingale typically installs one or two drones. “We can cover about 100 acres with one or two systems,” Wu said. “Each drone can fly for 30 minutes and takes 35 to 45 minutes to charge, depending on the state of the battery and also the temperature. The average construction-related mission is 12 to 15 minutes long, so if you have three of the systems, you can set up persistent overwatch, with one up in the air, one charging and one ready to go.”

Drones are typically set up to patrol specific places, “such as temporary warehouses where construction materials are stored, or areas with expensive equipment,” Wu said. Nightingale is working on a self-contained trailer-based drone system “that we can just drop off, and after one site is finished, a company can move it to another site,” he added. “It would have its own power and network. You can just drive it someplace and unhitch it, and it’s ready to go.”

Missions are usually scheduled after dark and after dinner. “Criminals got to eat too,” Wu said. “And sites are more likely to get hit later in the evening, although a lot of these criminal might also have day jobs, so they have to go home to sleep—theft is just a side hustle.”

PART OF THE TEAM

Drones “are not a panacea, of course,” Wu said. “Physical security is a team sport. What drones are is a force multiplier than can make security a lot more effective. They can work with security guards and perimeter sensors to become part of a team.”

For instance, “there are certain things humans can do that drones can’t, like make judgment calls,” Wu said. “Are teens on a site smoking marijuana or going off-roading on dirt bikes or 4-by-4s in the area, but not stealing anything? Or are there guys casing the area, and do you want to know what cars they are driving?”

In addition, “some customers will set up perimeter sensors—for instance, cameras, or some portable kinetic sensor on a fence,” Wu said. “If a sensor goes off, a drone can be dispatched to respond to the intrusion location to see what is going on.”

Nevertheless, the many benefits of drones and the growth in construction theft may drive companies to pursue drone security, Wu said. “If thieves can get away with theft, they will come back.”